- The Hitch-Hiker (1953) (Ida Lupino): 100% A+

- The Babadook (2014) (Jennifer Kent): 98% A+

- A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (Ana Lily Amirpour): 96% A+

- Raw (2016) (Julia Ducournau): 92% A-

Wednesday, March 18, 2020

Praise and Condemnation as Tools for Writers' Self-Appraisal

Friday, May 13, 2011

Academy Award-Winning Horror Films, 1931 - 2007

These horror films won Academy Awards:

Rosemary’s Baby (1983): Best Supporting Actress, Ruth Gordon

The Exorcist (1983): Best Sound, Robert Knudson and Best Adapted Screenplay, William Peter Blatty

Aliens (1986): Best Visual Effects, Robert Stotak, Stan Winston, John Richardson, and Suzanne M. Benson and Best Sound Effects Editing, Don Sharpe

The Silence of the Lambs (1991): Best Picture, Best Actress, Jody Foster, Best Actor, Anthony Hopkins, Best Director, Jonathan Demme, and Best Adapted Screenplay, Ted Tally

Jurassic Park (1993); Best Visual Effects, Dennis Muren, Stan Winston, Phil Tippett and Michael Lantieri, Best Sound Mixing, Gary Summers, Gary Rydstrom, Shawn Murphy, Ron Judkins, and Best Sound Editing, Gary Rydstrom and Richard Hymns

Sunday, February 14, 2010

Imagining the End

This is the end, my friend,In “The Philosophy of Composition,” Edgar Allan Poe argues that the end of a story so important that it should be imagined before any of the story is actually written and that all incidents of the plot and other narrative details should drive inexorably toward this predetermined ending (without it being obvious, of course, to the reader).

Of all our elaborate plans, the end

Of everything that stands, the end

I’ll never look into your eyes again, the end. . . .

-- The Doors

Hollywood directors apparently believe that the means must justify the ends, too, as it were, and, to this end, more than a few have devised alternate endings to the same story. Wild, wooly Wikipedia, which seems to have an article on virtually everything, although some articles are more reliable than others, and some are fairly unreliable altogether, features an essay concerning these endings, including a list of many of the films that include them.

According to Wikipedia, an alternate ending is one “that was planned or debated but ultimately unused in favor of the actual ending.”

Some of the examples of these endings, courtesy of the same source, are:

1408: . . . Mike Enslin dies in the fire he causes. At his burial, his wife is approached by the hotel manager, offering his personal belongings. She refuses, and he lets her know that her husband did not die in vain. Back in his vehicle he listens to the tape recorder, and screams in fear as he sees Enslin’s burned deformed body in his back seat for only a moment. The film closes with an apparition of Mike Enslin still in 1408, muttering to himself, and finally exiting the room, hearing his daughter's voice. . . .

The Astronaut's Wife: When Spencer is killed, Jillian is not possessed by the alien. Instead, she moves out to the country. Sitting beneath a tree, looking up at the stars, she tunes her radio to the same signals Spencer was receiving while possessed by the alien--her twin babies controlling her movements from inside the womb, listening--and waiting. . . .

The Butterfly Effect: Evan watches a home video of his mother pregnant with him and returns to the memory of himself as a fetus. Convinced that his very existence has ruined the lives of those around him, he strangles himself with his umbilical cord and dies, stillborn. This “Director’s Cut” ending is much darker than the theatrical ending, where he simply stops himself from becoming friends with Kayleigh.

I could go on (and on), but it’s not my purpose, really, to discuss alternate endings per se or to give an exhaustive list of examples of them. My purpose is to discuss such endings as a means of devising plots that are not predictable.

For an alternate ending to serve the purpose I suggest, though, it would have to be more of a departure than the ones exemplified in Wikipedia.

Thursday, December 31, 2009

Humor versus Horror

In the sexist teen sex comedy, 100 Girls, college student Matthew (no last name) has sex with a coed student with whom he is trapped in a dark, stalled elevator. He awakens the next morning, still in the elevator, to find that his anonymous lover has abandoned him, leaving behind, perhaps as a memento of the occasion, a pair of her panties. In a twist on the idea of Prince Charming’s matching the glass slipper left by Cinderella at the masked ball to the foot of its owner, Matthew seeks the bra that he believes will match the panties. He adopts the strategy of posing as a maintenance man for the college’s women’s dormitory, or “virgin vault,” as he calls it, which impersonation provides him access to coeds’ dressers, wherein he can search for the holy grail, as it were, of the matching bra.

That’s how this situation is developed comically--at least in 100 Girls. How might the same storyline be developed in a horror story? Here’s one possibility:

College student Matthew (no last name) has sex with a coed student with whom he is trapped in a dark, stalled elevator. He awakens the next morning, still in the elevator, to find that his anonymous lover has abandoned him, leaving her glass eye behind her. In a twist on the idea of Prince Charming’s matching the glass slipper left by Cinderella at the masked ball to the foot of its owner, Matthew seeks the one-eyed woman, his “Miss Cyclops,” who owns the glass eye. He adopts the strategy of posing as a maintenance man for the college’s women’s dormitory, which impersonation provides him access to coeds’ rooms, wherein he can search for his “Miss Cyclops.”

Admittedly, this is not much of a storyline. It needs work--a lot of work--and maybe wouldn’t work at all. My point, though, is to indicate how a humorist and a horror writer can treat the same idea, each in his or her own way, which is to say, humorously or horrifically.

In a comedy, order gives way to confusion, but the conflict is usually not a life-and-death matter; typically, it is something lighthearted, insignificant, or even absurd, often with satirical overtones, and the story usually ends well. The theme may be meaningful, but the vehicle for its expression, the story itself, tends to be fluffy and fun.

In a horror story, stability likewise succumbs to chaos, but the conflict that ensues definitely is a life-and-death matter. The story may occasionally feature a lighthearted moment, by way of comedic relief, but, overall, the narrative or drama will be suspenseful, even terrifying, and an atmosphere of dread will pervade, right to the end, as a monster or other antagonist relentlessly and pitilessly pursues his or her (usually his) victims, piling up dead (and often mutilated) bodies like cordwood. The theme usually will be significant, although the story is unlikely to end well, even for the protagonist. In a word, comedies treat their subjects humorously; horror stories, horrifically. Even the same basic situation will take a turn for the better (in comedy) or for the worse (in horror), depending upon the writer’s intent and perspective.

For example, in 100 Girls, Matthew ends up with his mystery lover, whereas, in a horrific treatment of the story:

Matthew might be arrested, suspected of being the psychotic butcher who, for weeks, has been collecting women’s eyeballs. In jail, Matthew has no way to stop the real mutilator/killer, who wants to complete his set by collecting his latest victim’s second eyeball as well. Perhaps Matthew’s parents, mortgaging their house, post their son’s bail, and Matthew is able, then, to track down the true psycho, either in time to prevent him from claiming the coed’s other eye or arriving on the scene a few seconds too late to save her from this blinding fate.

Again, this extension of the plot is about as ludicrous as it is horrific, and it could use a lot more work. For one thing, it is derivative, not only of 100 Girls but also of Jeepers Creepers, a horror film in which a stalker collects women’s eyes. (Hollywood would no doubt solve this problem by making the antagonist of such a film a "copycat" killer, just as this sort of story would itself be a copycat of the original movie.) The derivative nature of the storyline, however, suggests that the tale could be not only told but sold, and indicates, further, that, in horror, the absurd is as welcome as it is in humor, provided that it is treated horrifically, rather than humorously, which means that there must be fear and, in many cases, gore, or, as Edgar Allan Poe, more eloquently phrases the same dictum:

That motley drama!--oh, be sure

It shall not be forgot!

With its Phantom chased for evermore,

By a crowd that seize it not,

Through a circle that ever returneth in

To the self-same spot;

And much of Madness, and more of Sin

And Horror, the soul of the plot!

Wednesday, December 31, 2008

Generating Horror Plots, Part II

1. Find the ugly within or among the beautiful. We discussed this strategy in a previous post.

2. Develop a continuing theme. We discussed this strategy in a previous post.

3. Enact revenge. We discussed this strategy in a previous post.

5. Find the strange in the familiar. Two specimens of this approach may be offered, one as much a failure as the other is a success. Although we have discussed them previously, we offer a truncated version of our previous discussions here to demonstrate the technique of finding the strange in the familiar. The failure is the film, The Happening (2008), which was directed by M. Night Shyamalan. As most horror stories of this kind begin, the movie starts by showing a series of bizarre, seemingly inexplicable occurrences: mass suicides and murders by individuals and groups whose behavior is markedly aberrant. As the series of such incidents continue, spreading from person to person, from group to group, and from town to town, various theories are considered and abandoned as to the cause of the strange happenings. Is a bio-terrorist attack behind the events? Is it an epidemic of some kind? A botanist thinks that plants may be responsible for the murder and mayhem, releasing airborne toxins to defend themselves against humanity. The protagonist, a scientist named Elliot Moore, and his wife Alma take refuge with an murdered friend and colleague’s orphaned daughter Hess inside an eccentric old woman’s house as the plants continue to press their attack. Their hostess becomes infected, but they escape her attempts to kill them and, later, leave the house, surprised to find that the attacks have ceased. Three months later, watching TV, Elliot, Alma, and their adopted daughter hear a newscaster warn that the mysterious happening might have been but “the first spot of a rash” to come. Alma discovers she is pregnant, and, as she and Elliot celebrate, another series of bizarre suicides and murders take place in France. The film seeks to find the strange in the familiar, seeing flowers and shrubs and trees, especially those which blow in high winds, to be as menacing as poisonous weeds, but it is difficult to fear vegetation, wind or no wind, and the suspense simply doesn’t build, despite the mad and dangerous behavior of the infected humans whom the plants are bent upon exterminating. The heavy-handed, moralistic environmentalist theme of the movie is about as profound in its delivery as a PETA ad. The plot suffers in other ways, as does the characterization of all the players, but these are matters outside the present concern. A story that is more successful in eliciting the strange within the familiar is Bram Stoker’s short story “Dracula’s Guest.” Stoker suggests, far more subtly and effectively than Shyamalan, that there may be prodigious unseen powers operating behind the scenes, so to speak, of the natural events that take place in a remote stretch of forested countryside outside Munich on Walpurgis Night. Stoker he suggests that a tall, thin man who’d appeared seemingly out of nowhere and vanished as abruptly after frightening the coachman’s horses and leaving the Englishman stranded in the countryside as twilight gathers toward Walpurgis Night may be the unseen watcher, and perhaps also the occult, supernatural force that seems to control such natural forces as the weather, the wolves, the effects of the blizzard, and the hail. Alternatively, a note to Herr Delbruck by Dracula suggests that Transylvanian count himself may be opposed to whatever supernatural force is controlling these forces of nature and that, as this power’s adversary, he is acting, for reasons of his own, as the Englishman’s protector, however short-lived this self-assigned role may turn out to be. Examples of other stories that are more or less successful in seeking the strange within the familiar are Stephen King’s From a Buick 8 and most of the stories by H. P. Lovecraft. Concerning the finding of the strange in the familiar, the reader is advised to peruse the several articles that we have posted previously on Thrillers and Chillers, under the heading “Everyday Horrors.”

Saturday, June 21, 2008

"The Addams Family" Technique

Cartoonist Charles Addams is the father of a truly bizarre family. “Dysfunctional” doesn’t begin to describe its dynamics. Headed by Gomez and Morticia, The Addams Family includes son Pugsley, daughter Wednesday, Uncle Fester, Grandmama, and the shaggy Cousin Itt. A disembodied hand, Thing, is a permanent houseguest. This unlikely cast of characters is waited upon hand and foot--in the case of Thing, literally--by a hulking butler named Lurch. They live on a weed-choked estate behind a wrought-iron fence in a Second Empire mansion, complete with a garden (of sorts). The cartoon appeared regularly in The New Yorker magazine.

The one-panel strip was eventually translated into a television situation comedy (sitcom) of the same title starring John Astin (Gomez), Caroline Jones (Morticia), Ken Weatherwax (Pugsley), Lisa Loring (Wednesday), Jackie Cogan (Uncle Fester), Blossom Rock (Grandmama), Felix Silla (Cousin Itt), and Ted Cassidy (Lurch and Thing). The cartoon is also the basis of The Addams Family movie (1991) which starred Raul Julia (Gomez), Angelica Huston (Morticia), Jimmy Workman (Pugsley), Christina Ricci (Wednesday), Christopher Lloyd (Uncle Fester), Judith Malina (Grandmama), John Franklin (Cousin Itt), Carel Stricken (Lurch) and Christopher Hart (Thing). The screenplay for the motion picture is available at Movie Script Place.

In addition to featuring the same characters and setting, the cartoon, sitcom, and movie all parodied the contemporary American nuclear family, inverting traditional family and American values. The Addamses found ordinary people and their interests either repulsive, puzzling, dull, or offensive, preferring their own bizarre, macabre, and peculiar pursuits. Gomez never stopped courting his wife. Morticia was fond of raising roses, from which, snipping the buds, she would retain the thorny stems, immersing them in ornate vases of water, and tend to her carnivorous plant. Wednesday (who is, as her name suggests, “full of woe”) delights in executing her Marie Antoinette doll by guillotine and enjoys electrocuting her brother in the family’s electric chair. Pugsley’s passion is wrecking his electric train by derailing the engine and cars or blowing it up with a well-placed stick of miniature dynamite. Uncle Fester likes to impress others with his trick of illuminating a light bulb simply by placing it in his mouth, and he often chases intruders with his blunderbuss. Grandmama, a witch, is forever trying new spells or potions. Vertically challenged Cousin Itt’s face--or, indeed, his entire head and body--is never seen, because his hair extends from his scalp to the floor. He rides around the mansion in his three-wheeled car and speaks in shrill gibberish that only the rest of the family can understand. A childhood friend of Gomez’s, Thing is a severed hand that pops out of cigar boxes, urns, and other containers throughout the house to deliver the mail and do other assorted odd jobs. The butler, Lurch, is a giant. He wears a tuxedo, maintains an expression and a posture that suggests that rigor mortis has set in a little early, and rumbles rather than speaks. A Frankenstein-like servant, Lurch, Morticia reminds Gomez, is part of many families and has the heart of an Addams. Much of the cartoon’s, sitcom’s, and movie’s humor derives from Lurch’s unfriendly demeanor and the chores he performs in his ungainly and deadpan manner.

The Addams Family suggests that there is a fine line between horror and humor, as do such television shows as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, The Munsters, Bewitched, and I Dream of Jeannie. Literary critics have found humor--quite a bit of it, in fact--even in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. The difference between whether an incident or a situation will be humorous of horrific depends, of course, upon its treatment. Typically, humor will look for opportunities to exaggerate or understate the significance of ordinary incidents and situations, will seek the absurdity in daily activities and the pompous or inappropriate behavior of characters who are out of their depth or in an environment foreign to them, and so forth, whereas horror will seek the bizarre, the uncanny, the eerie, the frightening, and the incongruous in such incidents and situations with an eye not to how and why these incidents and situations are amusing but as to why they are in some way menacing.

Cartoonist Charles Addams is the father of a truly bizarre family. “Dysfunctional” doesn’t begin to describe its dynamics. Headed by Gomez and Morticia, The Addams Family includes son Pugsley, daughter Wednesday, Uncle Fester, Grandmama, and the shaggy Cousin Itt. A disembodied hand, Thing, is a permanent houseguest. This unlikely cast of characters is waited upon hand and foot--in the case of Thing, literally--by a hulking butler named Lurch. They live on a weed-choked estate behind a wrought-iron fence in a Second Empire mansion, complete with a garden (of sorts). The cartoon appeared regularly in The New Yorker magazine.

The one-panel strip was eventually translated into a television situation comedy (sitcom) of the same title starring John Astin (Gomez), Caroline Jones (Morticia), Ken Weatherwax (Pugsley), Lisa Loring (Wednesday), Jackie Cogan (Uncle Fester), Blossom Rock (Grandmama), Felix Silla (Cousin Itt), and Ted Cassidy (Lurch and Thing). The cartoon is also the basis of The Addams Family movie (1991) which starred Raul Julia (Gomez), Angelica Huston (Morticia), Jimmy Workman (Pugsley), Christina Ricci (Wednesday), Christopher Lloyd (Uncle Fester), Judith Malina (Grandmama), John Franklin (Cousin Itt), Carel Stricken (Lurch) and Christopher Hart (Thing). The screenplay for the motion picture is available at Movie Script Place.

In addition to featuring the same characters and setting, the cartoon, sitcom, and movie all parodied the contemporary American nuclear family, inverting traditional family and American values. The Addamses found ordinary people and their interests either repulsive, puzzling, dull, or offensive, preferring their own bizarre, macabre, and peculiar pursuits. Gomez never stopped courting his wife. Morticia was fond of raising roses, from which, snipping the buds, she would retain the thorny stems, immersing them in ornate vases of water, and tend to her carnivorous plant. Wednesday (who is, as her name suggests, “full of woe”) delights in executing her Marie Antoinette doll by guillotine and enjoys electrocuting her brother in the family’s electric chair. Pugsley’s passion is wrecking his electric train by derailing the engine and cars or blowing it up with a well-placed stick of miniature dynamite. Uncle Fester likes to impress others with his trick of illuminating a light bulb simply by placing it in his mouth, and he often chases intruders with his blunderbuss. Grandmama, a witch, is forever trying new spells or potions. Vertically challenged Cousin Itt’s face--or, indeed, his entire head and body--is never seen, because his hair extends from his scalp to the floor. He rides around the mansion in his three-wheeled car and speaks in shrill gibberish that only the rest of the family can understand. A childhood friend of Gomez’s, Thing is a severed hand that pops out of cigar boxes, urns, and other containers throughout the house to deliver the mail and do other assorted odd jobs. The butler, Lurch, is a giant. He wears a tuxedo, maintains an expression and a posture that suggests that rigor mortis has set in a little early, and rumbles rather than speaks. A Frankenstein-like servant, Lurch, Morticia reminds Gomez, is part of many families and has the heart of an Addams. Much of the cartoon’s, sitcom’s, and movie’s humor derives from Lurch’s unfriendly demeanor and the chores he performs in his ungainly and deadpan manner.

The Addams Family suggests that there is a fine line between horror and humor, as do such television shows as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, The Munsters, Bewitched, and I Dream of Jeannie. Literary critics have found humor--quite a bit of it, in fact--even in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. The difference between whether an incident or a situation will be humorous of horrific depends, of course, upon its treatment. Typically, humor will look for opportunities to exaggerate or understate the significance of ordinary incidents and situations, will seek the absurdity in daily activities and the pompous or inappropriate behavior of characters who are out of their depth or in an environment foreign to them, and so forth, whereas horror will seek the bizarre, the uncanny, the eerie, the frightening, and the incongruous in such incidents and situations with an eye not to how and why these incidents and situations are amusing but as to why they are in some way menacing.

It is menace that, ultimately, makes a situation horrific and dreadful. By applying The Addams Family technique to everyday situations and incidents and looking for the potential menace in them rather than for the potential humor in them, the horror writer can come up with plot material that might otherwise go unnoticed or unappreciated. The technique is simple, but effective: interpret commonplace incidents and situations from an out-of-kilter, offbeat, madcap point of view. Interpret figurative expressions literally and literal expressions figuratively. Imagine how the Addams family might interpret everyday events and occurrences or how they might understand the meaning of an innocuous phrase.

For example, were the Addams family to have a dinner party, the catered refreshments might include finger sandwiches that were truly finger sandwiches--severed human digits laid side by side between two slices of bread and garnished with lettuce, tomatoes, onions, and the dressing of one’s choice. The whole meal, in fact, would be likely to comprise a feast fit for cannibals. Now, take the humor out of the situation, and replace it with horror. Make a few other adjustments, lending the storyline as much verisimilitude as possible within the conditions of the audience’s willing suspension of disbelief, and viola!, The Addams Family principle has provided a plot for a horror story such as the maestro Stephen King might have written.

A bit of brainstorming--lovely word for horror writers!--may suggest other possibilities. The appetite among some Asians for dog flesh is well known. What better way to increase the stock of this delicacy in one’s freezer than to go to a large city park frequented by the owners of such pets and wait for one or more of them to walk their dogs past the perfect ambush site along the a woodland path?

Another idea? (Simply insert a 100-watt bulb into one’s mouth, Uncle Fester style.) How about this one? A vampire king’s five-hundredth “birthday” (that is, the night that he was transformed into one of the living dead) is approaching, and his followers want to get him something special to commemorate the occasion. They discuss various possibilities: blood bags from the local blood bank, the chorus girls from a popular Broadway (or Las Vegas) show, kindergartners from a local preschool or daycare center. Finally, they decide on five hundred virgins. The only problem is that they’re hard-pressed to locate such a vast number of this commodity. The story resulting from this premise would be partly funny and partly fiendish, much like The Addams Family itself, showing, once again, that it is possible to mix humor with horror (and even a little social commentary), as long as, if the story is to be considered horror rather than humor, the menace outweighs the clowning.

It is menace that, ultimately, makes a situation horrific and dreadful. By applying The Addams Family technique to everyday situations and incidents and looking for the potential menace in them rather than for the potential humor in them, the horror writer can come up with plot material that might otherwise go unnoticed or unappreciated. The technique is simple, but effective: interpret commonplace incidents and situations from an out-of-kilter, offbeat, madcap point of view. Interpret figurative expressions literally and literal expressions figuratively. Imagine how the Addams family might interpret everyday events and occurrences or how they might understand the meaning of an innocuous phrase.

For example, were the Addams family to have a dinner party, the catered refreshments might include finger sandwiches that were truly finger sandwiches--severed human digits laid side by side between two slices of bread and garnished with lettuce, tomatoes, onions, and the dressing of one’s choice. The whole meal, in fact, would be likely to comprise a feast fit for cannibals. Now, take the humor out of the situation, and replace it with horror. Make a few other adjustments, lending the storyline as much verisimilitude as possible within the conditions of the audience’s willing suspension of disbelief, and viola!, The Addams Family principle has provided a plot for a horror story such as the maestro Stephen King might have written.

A bit of brainstorming--lovely word for horror writers!--may suggest other possibilities. The appetite among some Asians for dog flesh is well known. What better way to increase the stock of this delicacy in one’s freezer than to go to a large city park frequented by the owners of such pets and wait for one or more of them to walk their dogs past the perfect ambush site along the a woodland path?

Another idea? (Simply insert a 100-watt bulb into one’s mouth, Uncle Fester style.) How about this one? A vampire king’s five-hundredth “birthday” (that is, the night that he was transformed into one of the living dead) is approaching, and his followers want to get him something special to commemorate the occasion. They discuss various possibilities: blood bags from the local blood bank, the chorus girls from a popular Broadway (or Las Vegas) show, kindergartners from a local preschool or daycare center. Finally, they decide on five hundred virgins. The only problem is that they’re hard-pressed to locate such a vast number of this commodity. The story resulting from this premise would be partly funny and partly fiendish, much like The Addams Family itself, showing, once again, that it is possible to mix humor with horror (and even a little social commentary), as long as, if the story is to be considered horror rather than humor, the menace outweighs the clowning.

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

Tag! You’re It!

His mind is her prison (The Cell).

This tagline suggests that the antagonist is likely to be a stalker. The tagline tells us that he is a male, and his prisoner is a female. His thoughts about the protagonist somehow imprison her. Apparently, he is obsessed with her. He is likely to have stalked her. Whether he has, in fact, kidnapped her is unspecified, but possible--even likely. This tagline is effective. In only five words, it identifies the type of protagonist (a victim) and antagonist (a stalker or a kidnapper) and the nature of the struggle between them. It also raises a few tantalizing questions. If she has been adducted, where is she being held captive (other than in his mind)? If “his mind is her prison,” is he a control freak and, perhaps, a sadist? If she is literally a captive, will she escape? If so, how? If not, why not? Does her captor kill her? In what manner, and why? Is torture involved?

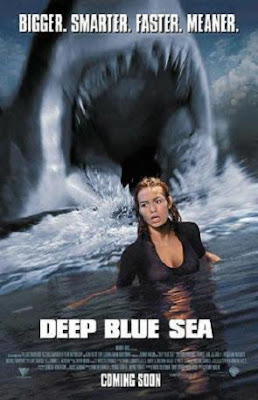

Bigger. Smarter. Faster. Meaner. (Deep Blue Sea)

What’s “bigger, smarter, faster, and meaner”? We aren’t told. Therefore, we’re free to imagine what these adjectives refer to. They could refer to a machine, to a new species resulting from bioengineering or eugenics, or to a robot or cyborg assassin. In fact, it’s a maritime threat, and the comparative forms of the adjectives in the tagline compare it, favorably, against the great white shark that appeared as the monster in Jaws. This tagline, in alluding to a previous movie, appeals to the fans of the Steven Spielberg film, but suggests that the movie to which it refers, Deep Blue Sea, will be even more chilling and thrilling than Jaws was. “If you liked Jaws,” it suggests, “you’ll love Deep Blue Sea.” After all, this movie, like its monster, will be “bigger, smarter, faster, and meaner” than Jaws.

Death doesn’t take “no” for an answer (Final Destination).Death is unavoidable; it “doesn’t take ‘no’ for an answer.” Therefore, the grave is our “final destination,” as the title of the movie, in the context supplied to it by its tagline, suggests. Of course, the tagline also suggests that we’re in imminent danger: death has asked us to join him (or it), and he (or it) is awaiting our answer--which had better be “yes,” since “Death doesn’t take no for an answer.” Is there a fate worse than death? Hamlet thought so:

To be, or not to be--that is the question: Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune Or to take arms against a sea of troubles And by opposing end them. To die, to sleep-- No more--and by a sleep to say we end The heartache, and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to. 'Tis a consummation Devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep-- To sleep--perchance to dream: ay, there's the rub, For in that sleep of death what dreams may come When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause. There's the respect That makes calamity of so long life. For who would bear the whips and scorns of time, Th' oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely The pangs of despised love, the law's delay, The insolence of office, and the spurns That patient merit of th' unworthy takes, When he himself might his quietus make With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscovered country, from whose bourn No traveller returns, puzzles the will, And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all, And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought, And enterprise of great pitch and moment With this regard their currents turn awry And lose the name of action. . . .

Many others, both fictional and living, believe the same thing, more or less, and are afraid that there may very well be “more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in. . . [their] philosophy,” including, perhaps, hell. The fear of damnation, which still beats within the breasts of many, is the wellspring of terror upon which the following tagline depends for its gush of dread, implying that, as great as it may be to lose one’s life, the loss of one’s eternal soul is unimaginably worse:

Many others, both fictional and living, believe the same thing, more or less, and are afraid that there may very well be “more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in. . . [their] philosophy,” including, perhaps, hell. The fear of damnation, which still beats within the breasts of many, is the wellspring of terror upon which the following tagline depends for its gush of dread, implying that, as great as it may be to lose one’s life, the loss of one’s eternal soul is unimaginably worse:

You have nothing to lose but your soul (Lost Souls)

The next tagline refers to a game, and a common metaphor compares life to a game:

The next tagline refers to a game, and a common metaphor compares life to a game:

The game is far from over (Along Came a Spider)Other types of games may spring to mind, too, such as the rather sadistic “game of cat and mouse,” wherein a predator amuses itself by tormenting its prey. If the game in question is life--and life, perhaps, spent in misery, as the victim of a sadist who amuses himself by tormenting his victim--and “the game is far from over,” a sense of horror asserts itself readily enough. (We were much more frightened when we thought that the tagline might refer to Hillary Clinton’s winning the White House! After all, she’s always assuring us--or herself, perhaps--that the Democratic primary, a game if ever there was one, “is far from over.”) Like most taglines, this one lacks a context--until the title of the movie with which it is associated is read. Along Came a Spider is taken from the “Little Miss Muffet” nursery rhyme:

Little Miss Muffet, sat on a tuffet, Eating her curds and whey; Along came a spider, who sat down beside her And frightened Miss Muffet away.

Therefore, this tagline comprises a literary allusion. After describing a picture of innocence and everyday comfort (a little girl, dining), the tagline introduces a threat--the spider, an unwelcome intruder, which violates the heroine’s personal space, sitting “down beside her,” and frightens her. The tagline also suggests that the nursery rhyme has some bearing upon the movie’s plot, theme or, perhaps, its protagonist or antagonist (or both). If we haven’t yet seen the film, we may not be sure of the exact nature of the significance the nursery rhyme has in regard to the film, but we can be pretty certain that, whatever it is, it will be horrendous, and that it will involve the frightening intrusion of a threat upon an innocent. (In fact, the allusion is a bit more tenuous than we might anticipate; the movie turns out to be more of a thriller than a chiller, the Little Miss Muffet of which is a congressman’s daughter who is abducted from a private school by the kidnapper, or “spider.”)

It doesn’t matter if you’re perfect. You will be (Disturbing Behavior).

Sure enough, the movie involves a plot by townspeople to transform their rebellious teens into perfect citizens. (Ironically, what’s “disturbing” about the teens’ behavior is that it’s literally too good to be true.)

The night has an appetite (The Forsaken).

Be careful who you trust (The Glass House).Pretty sound advice, even if it’s a tad general--especially in a horror movie. Some people, we learn, are not worthy of our trust. The movie’s title calls to mind another aphorism: “People who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones,” meaning that the pot is ill-advised to call the kettle black, since it takes one to know one or something like that. In this movie, the glass house, however, turns out to be the home of the Glasses, Terrence and Erin, who are the former Malibu neighbors of two siblings whose parents are killed in a car crash. After their parents’ deaths, the children, Ruby and Rhett Baker, are taken in by the Glasses, who treat them well--at first. Ruby then finds some evidence that suggests that the Glasses, motivated by the chance to get their greedy hands on their new wards’ four-million-dollar trust fund, may have been responsible for her parents’ deaths. The Glasses are not as transparent as they seem; they have some dark secrets. Once again, Mom’s Maxims prove to be right on the money. (An alternate tagline for this movie is “It’s time to kick some Glass.”)

What’s eating you? (Jeepers Creepers)

Jeepers Creepers, where’d you get those peepers? Jeepers Creepers, where’d you get those eyes? Gosh, all get up! How’d they get so lit up? Gosh, all get up! How’d they get that size? Golly gee! When you turn those heaters on, woe is me! Got to get my cheaters on. Jeepers Creepers, Where’d you get those peepers? Oh, those weepers! How they hypnotize! Where’d you get those eyes? Where’d you get those eyes? Where’d you get those eyes?

Be afraid. Be very afraid (The Fly).

In space, no one can hear you scream (Alien).

- They describe a basic situation that lacks a context, the context being provided by the title of the film for which the tagline is a pitch, making a sort of game out of the two elements (title and tagline).

- They pique our interest by identifying the main characters (protagonist and antagonist) and suggesting the nature of the conflict between them.

- They include plays on words that associate literal with figurative meanings, relating physical actions to emotional states.

- They allude to similar films, suggesting that they are better (read scarier) than their competitors.

- They confront their audience with a powerful, apparently unstoppable foe.

- They personify non-human threats.

- They place characters in nearly impossible situations that are likely to get them dismembered or killed (or both).

An opening paragraph in a short story, the first chapter of a novel, or the first fifteen minutes or so of a movie that accomplishes one of these feats is likely to hook its reader or viewer, too.

The aspiring writer isn’t--or shouldn’t be--too proud to beg, borrow, or steal--well, not steal, maybe--effective techniques wherever he or she may find them, including the lowly motion picture tagline. Nothing succeeds like success, after all, and, yes, sometimes “brevity” certainly is “the soul of wit,” as Shakespeare’s Polonius advised.

Paranormal vs. Supernatural: What’s the Diff?

Sometimes, in demonstrating how to brainstorm about an essay topic, selecting horror movies, I ask students to name the titles of as many such movies as spring to mind (seldom a difficult feat for them, as the genre remains quite popular among young adults). Then, I ask them to identify the monster, or threat--the antagonist, to use the proper terminology--that appears in each of the films they have named. Again, this is usually a quick and easy task. Finally, I ask them to group the films’ adversaries into one of three possible categories: natural, paranormal, or supernatural. This is where the fun begins.

It’s a simple enough matter, usually, to identify the threats which fall under the “natural” label, especially after I supply my students with the scientific definition of “nature”: everything that exists as either matter or energy (which are, of course, the same thing, in different forms--in other words, the universe itself. The supernatural is anything which falls outside, or is beyond, the universe: God, angels, demons, and the like, if they exist. Mad scientists, mutant cannibals (and just plain cannibals), serial killers, and such are examples of natural threats. So far, so simple.

What about borderline creatures, though? Are vampires, werewolves, and zombies, for example, natural or supernatural? And what about Freddy Krueger? In fact, what does the word “paranormal” mean, anyway? If the universe is nature and anything outside or beyond the universe is supernatural, where does the paranormal fit into the scheme of things?

According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word “paranormal,” formed of the prefix “para,” meaning alongside, and “normal,” meaning “conforming to common standards, usual,” was coined in 1920. The American Heritage Dictionary defines “paranormal” to mean “beyond the range of normal experience or scientific explanation.” In other words, the paranormal is not supernatural--it is not outside or beyond the universe; it is natural, but, at the present, at least, inexplicable, which is to say that science cannot yet explain its nature. The same dictionary offers, as examples of paranormal phenomena, telepathy and “a medium’s paranormal powers.”

Wikipedia offers a few other examples of such phenomena or of paranormal sciences, including the percentages of the American population which, according to a Gallup poll, believes in each phenomenon, shown here in parentheses: psychic or spiritual healing (54), extrasensory perception (ESP) (50), ghosts (42), demons (41), extraterrestrials (33), clairvoyance and prophecy (32), communication with the dead (28), astrology (28), witchcraft (26), reincarnation (25), and channeling (15); 36 percent believe in telepathy.

As can be seen from this list, which includes demons, ghosts, and witches along with psychics and extraterrestrials, there is a confusion as to which phenomena and which individuals belong to the paranormal and which belong to the supernatural categories. This confusion, I believe, results from the scientism of our age, which makes it fashionable for people who fancy themselves intelligent and educated to dismiss whatever cannot be explained scientifically or, if such phenomena cannot be entirely rejected, to classify them as as-yet inexplicable natural phenomena. That way, the existence of a supernatural realm need not be admitted or even entertained. Scientists tend to be materialists, believing that the real consists only of the twofold unity of matter and energy, not dualists who believe that there is both the material (matter and energy) and the spiritual, or supernatural. If so, everything that was once regarded as having been supernatural will be regarded (if it cannot be dismissed) as paranormal and, maybe, if and when it is explained by science, as natural. Indeed, Sigmund Freud sought to explain even God as but a natural--and in Freud’s opinion, an obsolete--phenomenon.

Meanwhile, among skeptics, there is an ongoing campaign to eliminate the paranormal by explaining them as products of ignorance, misunderstanding, or deceit. Ridicule is also a tactic that skeptics sometimes employ in this campaign. For example, The Skeptics’ Dictionary contends that the perception of some “events” as being of a paranormal nature may be attributed to “ignorance or magical thinking.” The dictionary is equally suspicious of each individual phenomenon or “paranormal science” as well. Concerning psychics’ alleged ability to discern future events, for example, The Skeptic’s Dictionary quotes Jay Leno (“How come you never see a headline like 'Psychic Wins Lottery'?”), following with a number of similar observations:

Psychics don't rely on psychics to warn them of impending disasters. Psychics don't predict their own deaths or diseases. They go to the dentist like the rest of us. They're as surprised and disturbed as the rest of us when they have to call a plumber or an electrician to fix some defect at home. Their planes are delayed without their being able to anticipate the delays. If they want to know something about Abraham Lincoln, they go to the library; they don't try to talk to Abe's spirit. In short, psychics live by the known laws of nature except when they are playing the psychic game with people.In An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural, James Randi, a magician who exercises a skeptical attitude toward all things alleged to be paranormal or supernatural, takes issue with the notion of such phenomena as well, often employing the same arguments and rhetorical strategies as The Skeptic’s Dictionary.

In short, the difference between the paranormal and the supernatural lies in whether one is a materialist, believing in only the existence of matter and energy, or a dualist, believing in the existence of both matter and energy and spirit. If one maintains a belief in the reality of the spiritual, he or she will classify such entities as angels, demons, ghosts, gods, vampires, and other threats of a spiritual nature as supernatural, rather than paranormal, phenomena. He or she may also include witches (because, although they are human, they are empowered by the devil, who is himself a supernatural entity) and other natural threats that are energized, so to speak, by a power that transcends nature and is, as such, outside or beyond the universe. Otherwise, one is likely to reject the supernatural as a category altogether, identifying every inexplicable phenomenon as paranormal, whether it is dark matter or a teenage werewolf. Indeed, some scientists dedicate at least part of their time to debunking allegedly paranormal phenomena, explaining what natural conditions or processes may explain them, as the author of The Serpent and the Rainbow explains the creation of zombies by voodoo priests.

Based upon my recent reading of Tzvetan Todorov's The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to the Fantastic, I add the following addendum to this essay.

According to Todorov:

The fantastic. . . lasts only as long as a certain hesitation [in deciding] whether or not what they [the reader and the protagonist] perceive derives from "reality" as it exists in the common opinion. . . . If he [the reader] decides that the laws of reality remain intact and permit an explanation of the phenomena described, we can say that the work belongs to the another genre [than the fantastic]: the uncanny. If, on the contrary, he decides that new laws of nature must be entertained to account for the phenomena, we enter the genre of the marvelous (The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre, 41).Todorov further differentiates these two categories by characterizing the uncanny as “the supernatural explained” and the marvelous as “the supernatural accepted” (41-42).

Interestingly, the prejudice against even the possibility of the supernatural’s existence which is implicit in the designation of natural versus paranormal phenomena, which excludes any consideration of the supernatural, suggests that there are no marvelous phenomena; instead, there can be only the uncanny. Consequently, for those who subscribe to this view, the fantastic itself no longer exists in this scheme, for the fantastic depends, as Todorov points out, upon the tension of indecision concerning to which category an incident belongs, the natural or the supernatural. The paranormal is understood, by those who posit it, in lieu of the supernatural, as the natural as yet unexplained.

And now, back to a fate worse than death: grading students’ papers.

My Cup of Blood

Anyway, this is what I happen to like in horror fiction:

Small-town settings in which I get to know the townspeople, both the good, the bad, and the ugly. For this reason alone, I’m a sucker for most of Stephen King’s novels. Most of them, from 'Salem's Lot to Under the Dome, are set in small towns that are peopled by the good, the bad, and the ugly. Part of the appeal here, granted, is the sense of community that such settings entail.

Isolated settings, such as caves, desert wastelands, islands, mountaintops, space, swamps, where characters are cut off from civilization and culture and must survive and thrive or die on their own, without assistance, by their wits and other personal resources. Many are the examples of such novels and screenplays, but Alien, The Shining, The Descent, Desperation, and The Island of Dr. Moreau, are some of the ones that come readily to mind.

Total institutions as settings. Camps, hospitals, military installations, nursing homes, prisons, resorts, spaceships, and other worlds unto themselves are examples of such settings, and Sleepaway Camp, Coma, The Green Mile, and Aliens are some of the novels or films that take place in such settings.

Anecdotal scenes--in other words, short scenes that showcase a character--usually, an unusual, even eccentric, character. Both Dean Koontz and the dynamic duo, Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, excel at this, so I keep reading their series (although Koontz’s canine companions frequently--indeed, almost always--annoy, as does his relentless optimism).

Atmosphere, mood, and tone. Here, King is king, but so is Bentley Little. In the use of description to terrorize and horrify, both are masters of the craft.

Innovation. Bram Stoker demonstrates it, especially in his short story “Dracula’s Guest,” as does H. P. Lovecraft, Edgar Allan Poe, Shirley Jackson, and a host of other, mostly classical, horror novelists and short story writers. For an example, check out my post on Stoker’s story, which is a real stoker, to be sure. Stephen King shows innovation, too, in ‘Salem’s Lot, The Shining, It, and other novels. One might even argue that Dean Koontz’s something-for-everyone, cross-genre writing is innovative; he seems to have been one of the first, if not the first, to pen such tales.

Technique. Check out Frank Peretti’s use of maps and his allusions to the senses in Monster; my post on this very topic is worth a look, if I do say so myself, which, of course, I do. Opening chapters that accomplish a multitude of narrative purposes (not usually all at once, but successively) are attractive, too, and Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child are as good as anyone, and better than many, at this art.

A connective universe--a mythos, if you will, such as both H. P. Lovecraft and Stephen King, and, to a lesser extent, Dean Koontz, Bentley Little, and even Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child have created through the use of recurring settings, characters, themes, and other elements of fiction.

A lack of pretentiousness. Dean Koontz has it, as do Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, Bentley Little, and (to some extent, although he has become condescending and self-indulgent of late, Stephen King); unfortunately, both Dan Simmons and Robert McCammon have become too self-important in their later works, Simmons almost to the point of becoming unreadable. Come on, people, you’re writing about monsters--you should be humble.

Longevity. Writers who have been around for a while usually get better, Stephen King, Dan Simmons, and Robert McCammon excepted.