Copyright 2007 by Gary L. Pullman

My analysis of a number of horror novels, short stories, and movies has turned up no fewer than two dozen plots that are routinely used in horror, fantasy, science fiction, horror, and other genres of popular fiction. Don’t be surprised if they pop up in a few classic literary texts, too.

Invasion: An outside threat attacks a community. The community may be idealized, as a near-perfect place to live. Many residents are likely to be introduced. The reader is apt to like or sympathize with many of them. A few may be unlikable because they are arrogant, condescending, cruel, obscene, racist, or unfaithful. Some of these may become victims of the entity or force that attacks the community. Although the community may be a total institution, such as a hospice, a hotel, a nursing home, a private school, or a prison, it is often an entire town. A community, to some extent, may be regarded as an extension of one's home, as the term "hometown" suggests; therefore, one's neighbors may be regarded as one's extended family. In attacking a community, the invader is attacking one's home and family, both immediate and extended. Examples of novels and movies that are based on the Invasion plot are Invaders From Mars, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Relic, ‘Salem’s Lot, It, Desperation, The Regulators, Summer of Night, The Taking, and Stinger. A non-fantasy/horror/science fiction story that is based on the Invasion plot is Taps, in which the students at a military academy repel an attempt by the police to shut down the school (to allow its conversion into a condominium complex) and, ultimately, take on the National Guard. Prototype: Satan’s invasion of the Garden of Eden in Genesis.

Fools Rush In: Characters enter the monster’s lair: To conduct a rescue, to neutralize a threat, to capture an unusual animal, to gather plants that may be the source for a new miracle drug, to conduct scientific research, or for a number of other (sometimes foolish) reasons, a character or, more often, a team of characters, enters the place in which a dangerous entity or force resides or is located, and the entity or force protects its territory with disastrous results for the character or team that has entered its lair. Examples of novels and movies that are based on the Fools Rush In plot include Alien, Predator, King Kong, Anaconda, Subterranean, and Descent.

Let Sleeping Dogs Lie: Characters seek to capture, kill, or otherwise abuse or exploit a monster: This plot is a subtype of the fools rush in plot in which a character or team of characters enters the territory of an unusual organism specifically to capture it or to kill it. The reason for wanting to capture it varies. The capture may be for the purpose of displaying the organism, studying it, or neutralizing it. Examples of novels and movies that are based on the Let Sleeping Dogs Lie plot are King Kong, Anaconda, and Predator.

Serendipity: A chance discovery leads to mayhem. The Thing, Alien, and Rendezvous With Rama are based on the Serendipity plot. Prototype: Pandora’s Box।

Hubris: Pride goes before a fall: (Frankenstein, Jurassic Park, The Island of Dr. Moreau). Prototype: Satan’s rebellion against God in Paradise Lost, which is suggested, but not dramatized, in the Bible.

Deliverance: A hero or a company of heroes seeks to slay or otherwise get rid of a monster: Often, this plot, although it can stand alone, is an extension of the Invasion plot. Once the invader has invaded, one or more characters seek to deliver the community by evicting the invader. Occasionally, the character or characters may travel from one location to another in pursuit of the invader, driving him, her, or it from one invaded community after another. Examples of novels and movies that are based on the Deliverance plot are Beowulf, The Exorcist, It, Summer of Night, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and The Taking. Examples of non-fantasy/horror/science fiction stories that are based on the Deliverance plot are Have Gun, Will Travel, The A Team, and Pale Rider. In Have Gun, Will Travel, a gunfighter offers his services for hire, sometimes in the deliverance of a town that is being run by corrupt officials and their hired guns. The A Team is a group of four Vietnam veterans, framed for a crime they didn't commit, who help the innocent while on the run from the military; often, their help consists of ridding a town or a group of people of a bully. In Pale Rider, a gunfighter poses as a preacher for a group of gold prospectors, delivering them from local gunmen when he seeks revenge for having been shot and whipped by the gunmen and their leader. Prototype: Moses’ deliverance of the Israelites from Egyptian bondage in Exodus.

Call To Duty: A prophecy must be fulfilled, a quest must be undertaken, or a mission must be accomplished: Often the call to duty has worldwide, or even cosmic, implications and long-lasting, or even eternal, consequences and may involve supernatural entities and forces, including God and his angels or Satan and his demons. Examples of novels and movies that are based on the Call to Duty plot are Excalibur!, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, The Dark Crystal, Star Wars, It, and Summer of Night. Prototype: Abraham’s call to become the “father of many nations,” which was preceded, on a smaller scale, by God’s call to Noah to build the ark that saves a remnant of humanity (Noah and his family) from the universal flood of God’s wrath against sin.

Need To Feed: A monster is hungry; people are its food: To survive, characters must figure out a way to outsmart or circumvent the monster. The Need To Feed plot may be regarded as the Freudian oral stage of psychosexual development out of control. Examples of novels and movies that are based on the Need To Feed plot are Tremors, Jaws, and Dracula.

Need To Breed: A monster needs to reproduce, but, to do so, it requires a human mate: A search, with a series of fatalities, may be needed before the monster can find the right mate with which to breed, and the breeding itself may have fatal consequences to the human partner. Sometimes, the Need To Breed takes a technological rather than a biological form, as in Rejuvenator and Demon Seed. Examples of novels and movies that are based on the Need To Feed plot are Species, Rosemary‘s Baby, and Demon Seed.

Something To Prove: The main character has something to prove--courage, innocence, judgment: Jurassic Park is, in part, based on the Something To Prove plot.

Too Good To Be True: Beware a bargain! The main character makes a deal, usually with the devil, only to find that the price that he or she must pay far outweighs the benefits, power, or gift that he or she receives in exchange: (“What profits a man who gains the world and loses his own soul?”) Examples of novels and movies that are based on the Too Good To Be True plot are Faust, The Amityville Horror, Needful Things, and The Devil’s Apprentice.

Redemption or Assuaged Guilt: A character attempts to redeem him- or herself or someone else (a family member or a friend) for a past misdeed: Usually, the past misdeeds will be monstrous--far greater wrongs than are done by most other people (matricide, patricide, the killing of a sibling, rape, perjury that results in another person’s imprisonment or execution)-- and, consequently, the redemption, if it comes at all, will be a laborious and protracted process. Often, the character will doubt that he or she can ever be pardoned or forgiven and that, for him or her, the whole process is futile; nevertheless, out of a guilt and a sense, perhaps, of moral responsibility, if not hope for ultimate redemption, the tortured character will persist in performing his or her penance. Example of stories that are based on the Assuaged Guilt plot are The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Angel. Prototype: The redemption of humanity in Christ, as told in the Gospels.

Avengers, Assemble!: A wronged person seeks revenge (A Nightmare on Elm Street, The Abominable Dr. Phibes, The X-Men). Non-fantasy/horror/science fiction movies that are based on the Avengers, Assemble! plot are Sudden Impact, in which the sister of a woman whose gang rape caused her to become catatonic becomes a vigilante, avenging her sister by tracking down and killing her assailants; Rolling Thunder, in which a war hero seeks revenge against the thugs who, in stealing silver dollars from him, kill his wife and son and destroy his hand; and the Death Wish series, in which A New York City architect becomes a one-man vigilante squad against those who have killed his wife, his daughter, and other innocent people.

The Devil Made Me Do It: A character does evil because he or she is possessed by the devil or a demon or is the literal or figurative child of Satan: Examples of novels and movies that are based on The Devil Made Me Do It plot are The Exorcist, The Omen, Faust, The Regulators, Desperation, and The Devil‘s Advocate). Prototype: Satan’s tempting of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden in Genesis.

Greed: Greed outweighs common sense and decency; as a result, someone is usually maimed or killed: In part, King Kong, Jaws, and Poltergeist are based on the Greed plot.

People Are Such Animals!: Men and women turn into beasts: Such transformation stories tap into the sometimes-fine line between the human and the bestial, suggesting that, despite art, culture, and civilization, human beings are closer to the so-called lower animals than they’d care to admit and may act on the same instincts as those upon which animals act, especially on the need to feed and the need to breed. Usually, the only way to end the nightmare is to kill the beast. Examples of novels and films that are based on the People Are Such Animals! Plot are Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Wolfman, The Howling, and Silver Bullet.

Experiment Goes Awry: A mad scientist’s research runs amuck: This is often a subtype of the Hubris plot, the scientist’s arrogance leading to his or her manipulation of nature with disastrous, unforeseen effects. Examples of novels and movies that are based on the Invasion plot are Frankenstein, The Fly, The Island of Dr, Moreau, The Invisible Man, and The Food of the Gods.

Cannibals: Human monsters enjoy gourmet food--people: Examples of novels and movies that are based on the Cannibals plot are Soylent Green, The Silence of the Lambs, The Hills Have Eyes, and Ravenous.

Wrong Turn: A simple mistake or a purposeful cover up has fatal consequences: Wrong Turn and I Know What You Did Last Summer are based on the Wrong Turn plot.

Ragnarok: Something or someone is trying to end the world, often as a prelude to establishing a world of its own: This plot differs from the Invasion plot because the antagonist’s threat is not merely occupation but the annihilation of the invaded community, and the community is not merely a total institution or a town, but the entire world (although the annihilation may begin on a local scale). Examples of novels and movies that are based on the Ragnarok plot are War of the Worlds, Invaders From Mars, and The Taking. Prototypes: Revelation in the Bible, Ragnarok (in Norse mythology).

Starting Over: Having survived an apocalyptic catastrophe, natural or man-made, such as a universal flood, a nuclear holocaust, or a plague, a remnant of humanity overcomes extreme hardship and dangers as they rebuild their lost civilization. This plot requires a vast setting and many characters. Often, several small groups will compete against one another for dominance or to become the sole survival, Examples of novels and movies that are based on the Post-apocalyptic Starting Over plot are Damnation Alley, The Stand, Swan’s Song, A Boy and His Dog, The Omega Man, and Road Warrior (a. k. a. Mad Max II).

Dystopia: The world has gone to hell, without the hand basket: The dystopian world is the opposite of a utopia, or heaven on earth, in which, frequently, human beings have been reduced to slavery and are ruled by a ruthless, often barbaric, elite. George Orwell's 1984 and Aldous Huxley's Brave New World are non-horror examples, as is Fritz Lang's Metropolis.

Do or Die: A heroic character must complete a series of tasks or he or someone he loves will be killed; sometimes, a clock is ticking: An examples of a story that is based on the Do or Die plot is Dean Koontz's Velocity. Prototype: The 12 Labors of Hercules.

Copycat Killers: Crimes (usually murder) are based on urban legends or are copied from other, previous crimes. Often, in committing these crimes, the perpetrator seeks to share the notoriety of the original criminal (Urban Legends).

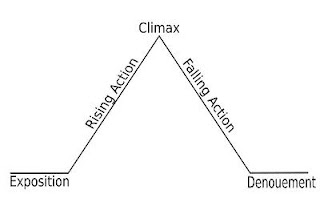

Building Up the Plot

The 24 basic plots identified above may be too simple, by themselves, to keep readers or moviegoers interested in the story. However, they provide the foundation for building a more complex plot that will keep readers or audience members’ interest. These are some ways that writers build from the 24 simple plots to more complex plots:

Outer and Inner: Relate the basic plot’s outer (natural or social) conflict to the protagonist’s inner (psychological) conflict: For example, in The Exorcist, the battle is between the priest and the devil, but it is also a struggle between the priest and himself, as he tries to hold on to the tattered remnants of his faith, which was shattered by his mother’s protracted suffering and death (a concrete example of the philosophical concern for the so-called problem of evil).

Bigger Is Better: Relate the basic plot’s outer conflict to an area of human concern (religion, politics, art, science) that is bigger than the protagonist and his or her immediate concerns: In Pale Rider, the protagonist avenges himself against sadistic men who shot and beat him; in the process, he prevents similar men from expelling gold prospectors from their goldfield and the denial of the better life that they hope to create for their families with the gold that they find. The individual, while serving his own needs, serves those of the community (or the world).

Fantastic Reality: The basic plot’s outer plot, especially if it is fantastic, can be related to a realistic psychological, social, or other outer struggle: In King Kong, the film producer who captures the giant ape hopes that, by displaying it for admission, he can avert the financial ruin that threatens him during the Great Depression.

Metaphorical Monsters: Make the monster a metaphor for a real-life problem that the protagonist faces (neglect, ostracism, drug addiction, spousal abuse); by vanquishing the monster (if vanquish it he or she does), the main character finds acceptance, self-acceptance, or freedom: In “Dead Man’s Party,” Buffy Summers attacks zombies which, as her friend Xander Harris informs her (and the viewer), are symbolic of thoughts, attitudes, and emotions that she has sought to repress: “You can't just bury stuff, Buffy. It'll come right back up to get you.”

Social Commentary: Like Huckleberry Finn, fantasy/science fiction/and horror novels and movies can provide social commentary about current events or eternal questions, examining such topics as dehumanization, euthanasia, interracial marriage, poverty, racism, religious intolerance, or repression of free speech, or war: The Regulators examines the negative effect of children’s television, particularly its violent content, on children’s thoughts, emotions, and behavior. Children of the Corn shows the murderous and suicidal results of an unquestioned devotion to religious doctrine. ‘Salem’s Lot and Needful Things shows the conformity, hypocrisy, corruption, and greed that often underlies the ideal image of the American small town.

Questioning Politically Correct Assumptions: Some fantasy/science fiction/and horror novels and movies question politically correct assumptions, one of which is that xenophobia is unnecessary and bigoted: Since it is directed at anyone who is a stranger, xenophobia is the most general form of bigotry, indiscriminate in its prejudice. One should welcome, not fear, strangers, critics of xenophobia contend. Such novels and movies as Childhood’s End challenge the truth of the politically correct assumptions behind xenophobia’s critics’ contentions. Offering friendship to strangers, these stories suggest, could get a person--or an entire people--or the whole human race--destroyed.

This Is That: This treatment of the basic plot is similar to that of the Bigger Is Better and the Metaphorical Monster treatment: In fact, it is a combination, of sorts, of these two treatments in which one state of affairs is a metaphor or an analogy for another, greater state of affairs that is similar to it. An example is Invasion of the Body Snatchers, which some critics contend, is, paradoxically, simultaneously both “an allegory for the loss of personal autonomy under Communism and as a satire of McCarthyist paranoia about Communism” (Wikipedia article on “Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956 film)”). A non-fantasy/science fiction/horror story that uses a This Is That plot treatment is Animal Farm, in which the farm represents a Communist society (Soviet Russia) ruled by an elite (the Communist Party, headed by Vladimir Lenin.)

Strength In Numbers: This treatment suggests the importance of community or at least cooperation among individuals, for it demonstrates that by such means, a group may vanquish a threat that individuals alone could not hope to conquer: Examples of this treatment abound and include It, Summer of Night, ‘Salem’s Lot, Desperation, The Regulators, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Star Wars, Excalibur!, The X-Men, Tremors, and many others.

New World Exploration: Another way to build a simple plot into a more complex one is to set the action in an undiscovered or new world. This treatment is especially appropriate for fantasy and science fiction novels. Even in novels set in the everyday world, a fresh perspective on a familiar environment can make the familiar seem unusual or bizarre. (Situation comedies often use this technique, making the main character or characters new kids on the block or fish out of water, as it were.) By displacing them from a familiar to a strange environment, writers broaden these characters’ experience; at the same time, writers can depict the new environment as it is seen by the displaced person. James Rollins frequently employs this technique in his novels, as do the writers of The Beverly Hillbillies television series.