Saturday, January 12, 2019

Voyeurism: Playing God

Thursday, March 31, 2011

Chillers and Thrillers: The Fiction of Fear

Something is similar with regard to the ultimate object of fear. Many persons, places, and things instill fear, but they all do it the same way--by threatening us with loss. The loss with which we're threatened is related to a significant possession, to something that we value highly: life, limb, mind, health, a loved one, and life itself are some possibilities.

It's been argued that we fear the unknown. I think that, yes, we do fear the unknown, but only because it may be associated with a possible threat to us or to something or someone else we value.

What is death? Simply annihilation? Or, as Hamlet suggests, is death but a prelude to something much worse, to possible damnation and an eternity of pain and suffering in which we're cut off from both God and humanity? That's loss, too--loss of companionship, friendship, communion, fellowship, and love. Against such huge losses, annihilation looks pretty cozy.

Horror fiction--the fiction of fear--wouldn't have much to offer us, though, if all it did was make us afraid of death and/or hell. It does do more, though, quite a bit more, as it turns out, which is why it's important in its own way.

First, if Stephen King (by way of Aristotle) is right, horror fiction provides a means both of exercising and of exorcising our inner demons. It allows us to become the monster for a time in order to rid ourselves of the nasty feelings and impulses we occasionally entertain. Horror fiction is cathartic. It allows us to vent the very feelings that, otherwise, bottled up inside, might make us become the monster permanently and drive us, as such, to murder and mayhem.

Horror fiction provides us with a way of exercising and of exorcising our inner demons, but it also reminds us that life is short, and it suggests to us that we should be grateful to be alive, that we should appreciate what we have, and that we should take nothing for granted--not life, limb, mind, health, loved ones, or anything else. Horror fiction is a literary memento mori, or reminder of death. In the shadow of death, we appreciate and enjoy the fullness of life.

No one ever wrote a horror story about a man who stubbed his toe or a woman who broke a nail. Horror fiction's themes are bigger; they're more important. They're as vast and profound as the most critically important and most highly valued of all things. Horror fiction, by threatening us with the loss of that which is really important, shows us what truly matters. As such, it's a guide, implicitly, to the good life.

Horror fiction also shows us, sometimes, at least, that no matter how bad things are, we can survive our losses. We can regroup, individually or collectively, subjectively or objectively, and we can continue to fight the good fight.

Chillers and thrillers are important for all these reasons and at least one other. They're entertaining to read or watch; they're fun!

Sources Cited:

King, Stephen, "Why We Crave Horror Movies," originally published in Playboy, 1982.

Thursday, September 23, 2010

Adolescent and Adult Themes

In any television series, a few (sometimes, many) episodes will be dedicated to establishing and developing the season’s arc, or the plot’s tangent. The other episodes in the season are often one- or two-part stories. As such, they suggest the types of themes, or topics, that a series of a particular type, directed toward a specific audience, may address. For example, Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer, directed at middle-class American teenagers and young adults, deals with themes of interest to such an audience. The series deals with unbridled ambition (“The Witch”), inappropriate adult-teen romance (“Teacher’s Pet”), the demands of duty and their conflict with personal desire (“Never Kill a Boy on the First Date”), the perils of negative peer pressure (“The Pack”), the dangers of young romance (“Angel”), the dangers of Internet dating (“I Robot, You Jane”), child abuse (“Nightmares”), the callous disregard for one who doesn’t measure up to the superficial standards of the clique (“Out of Sight, Out of Mind”)--and these all in the show’s first, shorter-than-normal season!

Although the episodes of horror or fantasy series that are written with an adult audience in mind may take the “monster of the week” approach, featuring a specific type of antagonist weekly or periodically, the episodes of such shows typically don’t deal with a specific concern that their viewers share They are not, in this sense, as didactic as shows oriented toward younger viewers. Instead, the more “adult” shows may seek to unsettle their audiences by suggesting that the world may be quite different than it seems and is generally understood to be and that, beyond the ordinary and the everyday, there may exist extraordinary and mysterious persons, places, and things.

The “Squeeze” episode of The X-Files is a good example, as is the series’ use of the skeptical, empirical Dana Scully as a foil to her more open-minded, experiential partner, Fox Mulder. Although both are Special Agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), each has his or her own investigatory methods.

Scully develops a profile of a suspect in a murder and the cannibalism that followed it (the killer ate the victim‘s liver), and, when, during a stakeout, she captures a suspect, Eugene Victor Tooms, he is subjected to a lie-detector test. Her investigatory methods are typical and routine.

Mulder, however, finds a fingerprint at the scene of a murder, and, using a computer program, matches the print to those that were found at several other murder scenes, and, during Tooms’ polygraph test, he asks several questions that makes his fellow agents doubt the validity of the test, and the suspect is released. The fingerprint that Mulder found is stretched out, which makes Mulder believe that Tooms may be a mutant who is able to elongate his body and who has a longer-than-human lifespan, sustained by his diet of human livers between his thirty-year periods of hibernation. Tooms, Mulder believes, committed not only the current murders but those in 1903, 1933, and 1963 as well.

Mulder’s investigatory methods are both routine (at times) and unusual, to say the least. He helps Scully to research Tooms. They can find neither a birth certificate nor a marriage certificate for the suspect, and the agents meet with a former detective, Frank Briggs, who tells them where Tooms resided in 1903. When Scully and Mulder visit the suspect’s apartment, they find it abandoned. However, Tooms manages to snare Scully’s necklace to add it to his collection of his murder victims’ possessions, which he keeps as souvenirs. Adopting another routine investigatory method, Mulder asks Scully to join him in another stakeout, this time of Tooms’ address, but they are instructed to abandon the surveillance.

Tooms enters Scully’s apartment through the ventilation system, but Mulder arrives in the proverbial nick of time, preventing Tooms from killing his partner, and the agents handcuff the killer. Tooms is subjected to medical tests that show that the killer has abnormal skeletal and muscular systems and an unusual metabolism. The jailed killer smiles when his guard delivers a meal, sliding the tray through the narrow slot in the prisoner’s barred door. Tooms has seen his escape route.

Scully represents the no-nonsense, realistic, down-to-earth, sensible, empirical, and skeptical adult, Mulder the open-minded, curious, even enthusiastic investigator of paranormal and supernatural phenomena who, by his own admission, wants “to believe.” The plots of the episodes play out between the extremes represented by Scully’s relative skeptical empiricism and Mulder’s relative faith and experiential approach to investigating the bizarre cases that seem to fall into his and his partner’s laps. Most adults would tend to side with Scully, seeing the world as largely understood and ordinary. The oddities, aliens, and monsters that appear, week after week, in one guise or another, on the show, however, suggest that Scully’s view may not be altogether effective in explaining some of the more mysterious experiences that he and Scully have or the stranger beings they meet. As Shakespeare’s open-minded Hamlet tells the skeptical Horatio, “There are more things in heaven and earth. . . than are dreamt of in your philosophy” (Hamlet, Act I, Scene 5, Lines 159-167).

That the world may not be what it seems frightens many adults, the same way that the monsters and villains of Buffy frighten younger audiences. Both series exemplify the uneasiness with which younger and older alike live their lives in stifled fear and trembling, looking, always over their shoulders and toward the ends of shadows, to see who--or what--is casting them.

Sunday, May 17, 2009

Characterization via Emotion

Characterization operates by means of depicting emotion. Literary characters are, in fact, embodiments of emotion. Some emotions may be negative, either in the sense that they are unpleasant or in the sense that they cause problems, personal, social, or otherwise. Emotions can also be positive because they are pleasant or because they alleviate or resolve problems, personal, social, or otherwise.

Characters’ responses to incidents--that is, their feelings concerning events--motivate their actions. In other words, characters are often reactive: they respond to internal or external stimuli. Internal stimuli are their own attitudes, beliefs, desires, fantasies, hopes, thoughts, and, of course, emotions, such as fear, love, and self-respect. External stimuli are persons, places, things, qualities, and ideas that elicit characters’ passions, and can include threats, money, beauty, and death.

The overall, consistent pattern which underlies and is discerned in an individual’s behavior over an extended period of time suggests his or her basic personality traits and causes him or her to be regarded as just, wise, kind, ruthless, arrogant, vain, or whatever. However, many lesser, secondary traits also comprise most fictional people at any time of his or her literary life.

Hamlet is driven by his sense of duty to avenge his murdered father, but he is also hesitant, wanting to make sure that he acts justly in killing his father’s true killer--if, indeed, his father was killed, as the spirit who alleges to be the ghost of his father contends the late king was. These traits are the primary ones that motivate Hamlet, both to act and to refrain from acting. Therefore, he can be said to be a dutiful and just, but hesitant, character. In short, we might regard him as being a man of valor.

His antagonist, who is also his uncle and his step-father, King Claudius, is shown to be cold, calculating, and unrepentant, and he is driven by lust, both for power and for sex, having married Hamlet’s mother, Gertrude, shortly after Hamlet’s father died. Therefore, Hamlet can be read as a dramatization of a conflict between these two sets of emotions: Hamlet’s dutifulness, justice, and hesitation collide with Claudius’ coldness, calculation, unwillingness to repent, and lust for power and sex.

Horror fiction is primarily about fear, but its characters are motivated by other emotions as well. Beowulf’s hero wants to prove his mettle as a warrior. Although The Exorcist’s Father Damian Karras has begin to doubt and, perhaps, to lose his faith, he remains a man of God who loves humanity, as it is represented in the possessed soul of young Regan MacNeil, enough to risk his own life in an attempt to exorcise the devil’s victim. Many of Stephen King’s characters are motivated by their need to bond and by their need to belong to a community, or by brotherly love, one might say.

Not only the protagonists of horror fiction are motivated by their emotions; their antagonists are as well. In Beowulf, the monstrous outcast, Grendel, attacks the Danes because he envies their camaraderie. In The Exorcist, the devil possesses Regan in an attempt to get Father Karras to renounce his faith and thus be damned. Many of King’s villains (‘Salem’s Lot’s Barlow, Andre Linoge in Storm of the Century, and the protean monster of It, for example) prey upon the weaknesses of small communities and their residents, motivated by their narcissistic desire to perpetuate themselves. The emotional conflicts in Beowulf, The Exorcist, and ‘Salem’s Lot can be represented this way:

Valor vs. EnvyBy motivating your characters to act according to their passions, you will make your fiction seem more realistic, and you will show what’s at stake, on a personal level, as it were, in the struggle between the story’s protagonist and antagonist. The nature of the struggle, in turn, may suggest your stories’ themes. For example, The Exorcist suggests that love casts out condemnation, just as Beowulf implies that valor vanquishes envy and King's novels indicate that brotherly love is more important than narcissistic self-perpetuation.

Love vs. Condemnation

Brotherly Love vs. Narcissistic self-perpetuation

Wednesday, July 9, 2008

Perennial Favorites

The ingredients of the horror plot are relatively few and relatively simple:

- A series of bizarre incidents or situations (or both).

- An explanation for the bizarre incidents or situations (or both).

- A battle with the monster in which the monster is defeated (using the knowledge gained by the explanation of the bizarre incidents or situations [or both]).

Usually, such a simple formula results in boredom pretty quickly. Even great literature, such as Voltaire’s Candide and Miguel Cervantes’ Don Quixote, built, as they are, on repetitions of the same plot device (the discovery of evil and suffering in various situations and the misunderstandings of incidents and situations because of a special species of madness, respectively) soon become rather tiresome. Why doesn’t horror fiction?

The answer, of course, is that quite a bit, even of the best of it, does become tiresome, sooner or later. Some stories don’t seem to wear out their welcome as quickly as other stories do or, another way of putting the same thing, some writers don’t seem to wear out their welcome as soon as others do. A few--Mary Shelley, Bram Stoker, Edgar Allan Poe, Bram Stoker, Robert Louis Stevenson, H. G. Wells, Shirley Jackson, Dean Koontz, Stephen King--are perennial favorites, some even long after their demise. (Those who regard Wells as strictly a science fiction writer haven’t read such novels as The Island of Dr. Moreau and The Food of the Gods or such short stories as “The Flowering of the Strange Orchid” and “The Red Room”.)

So what makes a horror story (or its author) a perennial favorite? There are lots of ingredients, but these are some of the more noticeable and longstanding

Mystery, especially when it is coupled with menace, is one of the secret ingredients of the perennial favorite. A sense of foreboding, communicated by the story’s tone and mood--its atmosphere--gets under the skin and stays under the skin sooner and longer than most of the story’s other elements, including, when there is an overt one present, the monster. The vehicle for the creation of such atmosphere is description. The writer who can write powerful descriptions is likely to write powerful fiction, and, when the fiction that he or she writes is horror, it will be horrific. The description of Poe’s House of Usher alerts the reader that the decaying mansion is likely, in some sense, to be haunted, even, perhaps, conscious and aware of itself and others, intentionally evil. Stoker’s description of the countryside through which Dracula’s guest wanders on Walpurgis Night suggests that a tremendously powerful force is operating behind the scenes of natural incidents. H. P. Lovecraft’s varied descriptions of the type of monster that menaces the protagonist and the villagers of the small town in his story, “The Lurking Fear,” takes place keeps the reader on the edge of his or her seat and the protagonist’s teeth on edge. The treatment of a horrendous game of chance as commonplace makes Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” a haunting tale. H. G. Wells’ descriptions of the mysterious incidents upon the remote jungle island upon which Dr. Moreau performs experiments as immoral as they are cruel and vicious keeps readers turning the pages, especially when the protagonist, Edward Prendick, believes he may be the doctor’s next victim. Mary Shelley’s description of the pitiful, but also terrifying and repulsive, creation of Victor von Frankenstein hooks her readers and keeps them hooked.

The knowledge that the hyper-masculine monster is much stronger, faster, and inhuman than the human characters adds to the suspense. How can a band of men and women survive against madmen, monsters, and supernatural threats that, too often, are motivated by impulses foreign to the vast majority of people and are not only dangerous but also frequently lethal? “It is a terrible thing,” Jonathan Edwards warned his congregation, “for a sinner to fall into the hands of the living God.” It is also a “terrible thing,” it seems, for a horror story protagonist to “fall into the hands of a living” madman, monster, or supernatural force or entity. How can a mere man or woman be expected to fight that which is far stronger and faster, but much less human, than they are? A boy told a news anchor what it was like to be picked up and flung by a tornado. It was terrifying, he said, because it made him feel helpless. The wind simply lifted and threw him as if he were nothing more than a rag doll. The same sense of terror and vulnerability would apply were a monster to attack, whether its victim was female or male.

The betrayal by a familiar and trusted family member, friend, or neighbor, or even a dog or everyday object, such as a toy, makes a story or an author popular and memorable, as Stephen King proves with such novels as Cujo, Christine, From a Buick 8, ‘Salem’s Lot, Desperation, The Regulators, and others, and as William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist, Dean Koontz’s The Good Guy and The Taking, and Dan Simmon’s Season of Night, to name but a few, indicate.

Mystery, menace, atmosphere, a powerful monster, and betrayal by one who is familiar and trusted are all ingredients of those horror stories, whether short stories or novels, that become perennial favorites, but one that stands out even more, perhaps, is these narratives’ worlds. The best of these writers have the gift of creating not only intriguing and eerie incidents and situations, sympathetic characters, and zigzagging plots, but each also creates a specific, self-contained world unto itself, full of memorable persons, places, and things. Whether this world is Elm Haven, Castle Rock, Derry, Desperation, Wentworth, a university campus (as in Bentley Little’s University), Dunwich, Arkham, Innsmouth, Kingsport, Moonlight Bay, or some other God-forsaken place, the perennial favorites among horror fiction and authors create their own worlds, replete with all the accoutrements of town, suburbs, or city, even, at times, maps of the streets, complete with the designations of the place’s residents’ houses. These writers make their readers part of a bigger community, giving them a home, no matter how humble and (eventually) dangerous, and the reader, becoming, as it were, him- or herself a fellow resident, at the very least, and possibly a friend, as it were, to one or more of the inhabitants of the story’s town, have themselves a stake in the incidents that occur there and in the outcome of these incidents and situations. It is unfortunate that another person’s house or town or state or country is attacked; it is catastrophic when one's own house, town, state, or country is the one that's attacked--and by a monster, at that! Therefore, to mystery, atmosphere, a powerful monster, and betrayal by one who is familiar, we must add the worst of all possible threats--the one to hearth and home, to family and friend. Look for this sense of community in the stories and novels of horror that have most struck your own fancy and which continue to enthrall and entertain you. It’s one of the horror writer’s most dependable and effective narrative techniques. Hillary Clinton was right about something, after all (sort of); it takes a village to raise the hackles.

Finally, horror fiction offers what no other type of genre can: a unique perspective. The world of horror is not safe (it’s full of monsters and menace, after all), but it’s unsafe in a way unlike the worlds of any other genre. Horror fiction’s ultimate theme is that, in the great roulette wheel in the sky upon which our lives are played out, there is the red (blood) and the black (death), and any spin of the wheel will land us on one or the other. Life, in short, is brutal, full of suffering, and ends, sooner or later (usually sooner, in horror fiction) in death, which may or may not be the end of it. (There could be, as Hamlet supposes, a worse place than the grave.) Life is painful. Life is harsh. Life is grievous. And then we die. However, life has its moments, mostly while the ball is still in motion and hasn’t lit, yet, on the red or the black, and, while the ball is hurtling round and round, we survive; perhaps, we even thrive. We go places, we see things, we might, on occasion, between the halt of the wheel and the jolting hops and skips that end on blood or death, even enjoy ourselves. In addition, since the game of chance that is our lives is viewed, in fiction, from the outside, vicariously through our identification with the little silver ball called the protagonist, we ourselves (although the same may not be said, always, for the protagonist) survive the trauma and the destruction of the red and the black, learning that we can endure despite pain and suffering and death. Meanwhile, the wheel spins, and the silver ball goes round and round, and where she will stop, no one knows (except that it will be on either the red or the black).

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

Tag! You’re It!

His mind is her prison (The Cell).

This tagline suggests that the antagonist is likely to be a stalker. The tagline tells us that he is a male, and his prisoner is a female. His thoughts about the protagonist somehow imprison her. Apparently, he is obsessed with her. He is likely to have stalked her. Whether he has, in fact, kidnapped her is unspecified, but possible--even likely. This tagline is effective. In only five words, it identifies the type of protagonist (a victim) and antagonist (a stalker or a kidnapper) and the nature of the struggle between them. It also raises a few tantalizing questions. If she has been adducted, where is she being held captive (other than in his mind)? If “his mind is her prison,” is he a control freak and, perhaps, a sadist? If she is literally a captive, will she escape? If so, how? If not, why not? Does her captor kill her? In what manner, and why? Is torture involved?

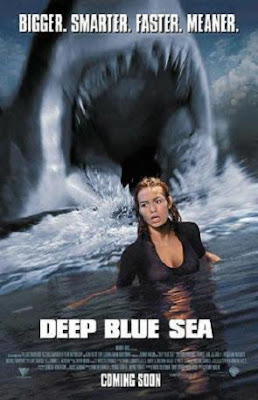

Bigger. Smarter. Faster. Meaner. (Deep Blue Sea)

What’s “bigger, smarter, faster, and meaner”? We aren’t told. Therefore, we’re free to imagine what these adjectives refer to. They could refer to a machine, to a new species resulting from bioengineering or eugenics, or to a robot or cyborg assassin. In fact, it’s a maritime threat, and the comparative forms of the adjectives in the tagline compare it, favorably, against the great white shark that appeared as the monster in Jaws. This tagline, in alluding to a previous movie, appeals to the fans of the Steven Spielberg film, but suggests that the movie to which it refers, Deep Blue Sea, will be even more chilling and thrilling than Jaws was. “If you liked Jaws,” it suggests, “you’ll love Deep Blue Sea.” After all, this movie, like its monster, will be “bigger, smarter, faster, and meaner” than Jaws.

Death doesn’t take “no” for an answer (Final Destination).Death is unavoidable; it “doesn’t take ‘no’ for an answer.” Therefore, the grave is our “final destination,” as the title of the movie, in the context supplied to it by its tagline, suggests. Of course, the tagline also suggests that we’re in imminent danger: death has asked us to join him (or it), and he (or it) is awaiting our answer--which had better be “yes,” since “Death doesn’t take no for an answer.” Is there a fate worse than death? Hamlet thought so:

To be, or not to be--that is the question: Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune Or to take arms against a sea of troubles And by opposing end them. To die, to sleep-- No more--and by a sleep to say we end The heartache, and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to. 'Tis a consummation Devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep-- To sleep--perchance to dream: ay, there's the rub, For in that sleep of death what dreams may come When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause. There's the respect That makes calamity of so long life. For who would bear the whips and scorns of time, Th' oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely The pangs of despised love, the law's delay, The insolence of office, and the spurns That patient merit of th' unworthy takes, When he himself might his quietus make With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscovered country, from whose bourn No traveller returns, puzzles the will, And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all, And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought, And enterprise of great pitch and moment With this regard their currents turn awry And lose the name of action. . . .

Many others, both fictional and living, believe the same thing, more or less, and are afraid that there may very well be “more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in. . . [their] philosophy,” including, perhaps, hell. The fear of damnation, which still beats within the breasts of many, is the wellspring of terror upon which the following tagline depends for its gush of dread, implying that, as great as it may be to lose one’s life, the loss of one’s eternal soul is unimaginably worse:

Many others, both fictional and living, believe the same thing, more or less, and are afraid that there may very well be “more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in. . . [their] philosophy,” including, perhaps, hell. The fear of damnation, which still beats within the breasts of many, is the wellspring of terror upon which the following tagline depends for its gush of dread, implying that, as great as it may be to lose one’s life, the loss of one’s eternal soul is unimaginably worse:

You have nothing to lose but your soul (Lost Souls)

The next tagline refers to a game, and a common metaphor compares life to a game:

The next tagline refers to a game, and a common metaphor compares life to a game:

The game is far from over (Along Came a Spider)Other types of games may spring to mind, too, such as the rather sadistic “game of cat and mouse,” wherein a predator amuses itself by tormenting its prey. If the game in question is life--and life, perhaps, spent in misery, as the victim of a sadist who amuses himself by tormenting his victim--and “the game is far from over,” a sense of horror asserts itself readily enough. (We were much more frightened when we thought that the tagline might refer to Hillary Clinton’s winning the White House! After all, she’s always assuring us--or herself, perhaps--that the Democratic primary, a game if ever there was one, “is far from over.”) Like most taglines, this one lacks a context--until the title of the movie with which it is associated is read. Along Came a Spider is taken from the “Little Miss Muffet” nursery rhyme:

Little Miss Muffet, sat on a tuffet, Eating her curds and whey; Along came a spider, who sat down beside her And frightened Miss Muffet away.

Therefore, this tagline comprises a literary allusion. After describing a picture of innocence and everyday comfort (a little girl, dining), the tagline introduces a threat--the spider, an unwelcome intruder, which violates the heroine’s personal space, sitting “down beside her,” and frightens her. The tagline also suggests that the nursery rhyme has some bearing upon the movie’s plot, theme or, perhaps, its protagonist or antagonist (or both). If we haven’t yet seen the film, we may not be sure of the exact nature of the significance the nursery rhyme has in regard to the film, but we can be pretty certain that, whatever it is, it will be horrendous, and that it will involve the frightening intrusion of a threat upon an innocent. (In fact, the allusion is a bit more tenuous than we might anticipate; the movie turns out to be more of a thriller than a chiller, the Little Miss Muffet of which is a congressman’s daughter who is abducted from a private school by the kidnapper, or “spider.”)

It doesn’t matter if you’re perfect. You will be (Disturbing Behavior).

Sure enough, the movie involves a plot by townspeople to transform their rebellious teens into perfect citizens. (Ironically, what’s “disturbing” about the teens’ behavior is that it’s literally too good to be true.)

The night has an appetite (The Forsaken).

Be careful who you trust (The Glass House).Pretty sound advice, even if it’s a tad general--especially in a horror movie. Some people, we learn, are not worthy of our trust. The movie’s title calls to mind another aphorism: “People who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones,” meaning that the pot is ill-advised to call the kettle black, since it takes one to know one or something like that. In this movie, the glass house, however, turns out to be the home of the Glasses, Terrence and Erin, who are the former Malibu neighbors of two siblings whose parents are killed in a car crash. After their parents’ deaths, the children, Ruby and Rhett Baker, are taken in by the Glasses, who treat them well--at first. Ruby then finds some evidence that suggests that the Glasses, motivated by the chance to get their greedy hands on their new wards’ four-million-dollar trust fund, may have been responsible for her parents’ deaths. The Glasses are not as transparent as they seem; they have some dark secrets. Once again, Mom’s Maxims prove to be right on the money. (An alternate tagline for this movie is “It’s time to kick some Glass.”)

What’s eating you? (Jeepers Creepers)

Jeepers Creepers, where’d you get those peepers? Jeepers Creepers, where’d you get those eyes? Gosh, all get up! How’d they get so lit up? Gosh, all get up! How’d they get that size? Golly gee! When you turn those heaters on, woe is me! Got to get my cheaters on. Jeepers Creepers, Where’d you get those peepers? Oh, those weepers! How they hypnotize! Where’d you get those eyes? Where’d you get those eyes? Where’d you get those eyes?

Be afraid. Be very afraid (The Fly).

In space, no one can hear you scream (Alien).

- They describe a basic situation that lacks a context, the context being provided by the title of the film for which the tagline is a pitch, making a sort of game out of the two elements (title and tagline).

- They pique our interest by identifying the main characters (protagonist and antagonist) and suggesting the nature of the conflict between them.

- They include plays on words that associate literal with figurative meanings, relating physical actions to emotional states.

- They allude to similar films, suggesting that they are better (read scarier) than their competitors.

- They confront their audience with a powerful, apparently unstoppable foe.

- They personify non-human threats.

- They place characters in nearly impossible situations that are likely to get them dismembered or killed (or both).

An opening paragraph in a short story, the first chapter of a novel, or the first fifteen minutes or so of a movie that accomplishes one of these feats is likely to hook its reader or viewer, too.

The aspiring writer isn’t--or shouldn’t be--too proud to beg, borrow, or steal--well, not steal, maybe--effective techniques wherever he or she may find them, including the lowly motion picture tagline. Nothing succeeds like success, after all, and, yes, sometimes “brevity” certainly is “the soul of wit,” as Shakespeare’s Polonius advised.

Friday, January 18, 2008

Poe and King: Two Unlikely Beauties

Structure has beauty. Unity has beauty. Coherence has beauty. Harmony and balance have beauty. A work, even if it treats of the horrifying and the terrifying, is beautiful if it exhibits these qualities. Edgar Allan Poe’s stories and poems show these attributes. Therefore, such narratives as The Raven, “The Tell-Tale Heart,” “The Cask of the Amontillado,” “The Masque of the Red Death,” and “The Pit and the Pendulum” are beautiful. They are works of art. Each word, each image, each figure of speech, and each part of the whole, in each case, builds toward a single effect--fear. Poe means to frighten his readers, and he carefully plots every incident of his story’s action to do just this. In his theory, outlined in “The Philosophy of Composition,” every word has a place in the bigger scheme of things, and every word must be in its place. The fact that his name remains in lights a century after his death is a measure of his success.

In horror fiction, Poe remains the master of masters. In our time, Stephen King is often held up as, well, the king of the horror genre. It’s doubtful that even King himself would claim to be of the same rank as Poe as a literary artist, though, however popular and prolific in output King may be. In fact, he refers to himself as the “literary equivalent of a Big Mac and fries.” Can it be said, though, that King has an aesthetics of horror? Maybe.

If we regard Aristotle as correct in his judgment that plot is the most important element of narrative, we may charge King with having an aesthetic. King knows how to tell a story, creating and maintaining suspense alongside pace and throwing a curve to his readers at just the right moment to keep them guessing (and reading). If Aristotle was right, King, in plotting his novels, might be said to create things of lasting beauty.

If, in striving for effect, Poe created whole new literary genres, King, in plotting his tales, recreated at least one--the horror genre. He took age-old, moldering themes, such as the vampire, and reenergized them. In bringing the parasitic bloodsuckers from Europe’s Gothic landscapes and installing them in small-town 'Salem's Lot, King not only gave them a local, and an American, home, but he also modernized them, making them, in a willing-suspension-of-disbelief-kind-of-way, believable and, therefore, frightening. King knows that home is not where one hangs one’s hat, but, rather, where one’s heart is, and, by making old world horrors at home in small-town America, he shocked and terrified and repulsed his countrymen, here and now. He also revolutionized the horror genre, which is no small feat in itself.

Home is Eden, King knows, and, so, he brought the serpent back into the garden. He did it by plotting his novels to demonstrate something simple but vital: what threatens one’s local community, one’s hometown, or one’s neighborhood, threatens oneself. That’s what’s scary nowadays, whether the threat takes the form of ancient vampires and werewolves or contemporary shape shifters and extraterrestrial entities beyond human ken.

Of course, some believe that Aristotle is mistaken about plot’s being the most important narrative element, pointing, instead, to character. The creation of memorable and significant literary personages who embody a great and lasting insight into humanity, as Hamlet, Othello, Macbeth, or even Scarlett O’Hara, does, is, these critics argue, what counts as great literary art. One Huckleberry Finn or Carrie White is worth any number of plots, they say.

If their point of view is true, King stands, on less certain ground in having developed a horror aesthetic, for, in fact, character doesn’t depend upon horror; stories of all types are peopled, as it were, with characters, many of high artistic quality. Many of Charles Dickens’ novels have little to do with horror as a genre that is represented by Poe, H. P. Lovecraft, King, and the like, but his characters certainly are giants among their peers or, in many cases, hey are peerless.

For many, Henry James solved the problem of plot, raised, on one hand, by Aristotle and of character, raised, on the other hand, by the philosopher’s critics, asserting that the two are but flip sides of the same coin. Action (the incidents of which comprise the plot) represents character, James suggested, just as character determines action. To put it in simpler terms, one is what one does, and what one does is what one is. An alcoholic, for example, is someone who drinks to excess, and someone who drinks to excess is an alcoholic. If James is right, in plotting the action of his novels, King is representing his characters, and his characters, in turn, determine what will happen in his books.

Action, one may quibble, is not the same as plot. Action is what happens; plot is how and why it happens. Action is what a character does; plot is how and why he or she does it. E. M. Forrester (I believe) distinguished between the two with a simple example--or two simple examples, actually. This is an example of action, he said:

The queen died. Then, the king died.

This is an example of plot, he said:

The queen died. Then, the king died of grief.

The addition of the two words “of grief” explain how and why the king died. In the first instance, there is no necessary connection between the incident of the queen’s death and that of the king’s demise. The two incidents are related strictly through chronological sequence: one happens before the other. In the second instance, there is a cause-and-effect relationship between the two incidents: the king’s grief, which was caused by the queen’s death, effects his own demise. A plot is a series of causally related incidents, each of which is cause by its antecedent and, in turn, causes its successor to occur.

In King’s fiction, bizarre, horrifying incidents (actions) occur with great regularity, but they don’t occur in a vacuum. They are related by a chain of cause and effect. Moreover, these plots happen in relation to a specific type of character--the man, woman, or child who lives in small-town, modern-day America. In tying together plots that involve strange incidents with today’s small-town residents, King unites past with present, old world with new world, tradition with innovation, childhood with adulthood, monsters with contemporary fears and anxieties. This marriage, whether made in heaven or in the other place, has a structure, a unity, a coherence, a harmony, and a balance that is beautiful to see--and to read. It seems safe to say that King’s horror fiction has an aesthetic; it’s just not lik, e Poe’s.

Paranormal vs. Supernatural: What’s the Diff?

Sometimes, in demonstrating how to brainstorm about an essay topic, selecting horror movies, I ask students to name the titles of as many such movies as spring to mind (seldom a difficult feat for them, as the genre remains quite popular among young adults). Then, I ask them to identify the monster, or threat--the antagonist, to use the proper terminology--that appears in each of the films they have named. Again, this is usually a quick and easy task. Finally, I ask them to group the films’ adversaries into one of three possible categories: natural, paranormal, or supernatural. This is where the fun begins.

It’s a simple enough matter, usually, to identify the threats which fall under the “natural” label, especially after I supply my students with the scientific definition of “nature”: everything that exists as either matter or energy (which are, of course, the same thing, in different forms--in other words, the universe itself. The supernatural is anything which falls outside, or is beyond, the universe: God, angels, demons, and the like, if they exist. Mad scientists, mutant cannibals (and just plain cannibals), serial killers, and such are examples of natural threats. So far, so simple.

What about borderline creatures, though? Are vampires, werewolves, and zombies, for example, natural or supernatural? And what about Freddy Krueger? In fact, what does the word “paranormal” mean, anyway? If the universe is nature and anything outside or beyond the universe is supernatural, where does the paranormal fit into the scheme of things?

According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word “paranormal,” formed of the prefix “para,” meaning alongside, and “normal,” meaning “conforming to common standards, usual,” was coined in 1920. The American Heritage Dictionary defines “paranormal” to mean “beyond the range of normal experience or scientific explanation.” In other words, the paranormal is not supernatural--it is not outside or beyond the universe; it is natural, but, at the present, at least, inexplicable, which is to say that science cannot yet explain its nature. The same dictionary offers, as examples of paranormal phenomena, telepathy and “a medium’s paranormal powers.”

Wikipedia offers a few other examples of such phenomena or of paranormal sciences, including the percentages of the American population which, according to a Gallup poll, believes in each phenomenon, shown here in parentheses: psychic or spiritual healing (54), extrasensory perception (ESP) (50), ghosts (42), demons (41), extraterrestrials (33), clairvoyance and prophecy (32), communication with the dead (28), astrology (28), witchcraft (26), reincarnation (25), and channeling (15); 36 percent believe in telepathy.

As can be seen from this list, which includes demons, ghosts, and witches along with psychics and extraterrestrials, there is a confusion as to which phenomena and which individuals belong to the paranormal and which belong to the supernatural categories. This confusion, I believe, results from the scientism of our age, which makes it fashionable for people who fancy themselves intelligent and educated to dismiss whatever cannot be explained scientifically or, if such phenomena cannot be entirely rejected, to classify them as as-yet inexplicable natural phenomena. That way, the existence of a supernatural realm need not be admitted or even entertained. Scientists tend to be materialists, believing that the real consists only of the twofold unity of matter and energy, not dualists who believe that there is both the material (matter and energy) and the spiritual, or supernatural. If so, everything that was once regarded as having been supernatural will be regarded (if it cannot be dismissed) as paranormal and, maybe, if and when it is explained by science, as natural. Indeed, Sigmund Freud sought to explain even God as but a natural--and in Freud’s opinion, an obsolete--phenomenon.

Meanwhile, among skeptics, there is an ongoing campaign to eliminate the paranormal by explaining them as products of ignorance, misunderstanding, or deceit. Ridicule is also a tactic that skeptics sometimes employ in this campaign. For example, The Skeptics’ Dictionary contends that the perception of some “events” as being of a paranormal nature may be attributed to “ignorance or magical thinking.” The dictionary is equally suspicious of each individual phenomenon or “paranormal science” as well. Concerning psychics’ alleged ability to discern future events, for example, The Skeptic’s Dictionary quotes Jay Leno (“How come you never see a headline like 'Psychic Wins Lottery'?”), following with a number of similar observations:

Psychics don't rely on psychics to warn them of impending disasters. Psychics don't predict their own deaths or diseases. They go to the dentist like the rest of us. They're as surprised and disturbed as the rest of us when they have to call a plumber or an electrician to fix some defect at home. Their planes are delayed without their being able to anticipate the delays. If they want to know something about Abraham Lincoln, they go to the library; they don't try to talk to Abe's spirit. In short, psychics live by the known laws of nature except when they are playing the psychic game with people.In An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural, James Randi, a magician who exercises a skeptical attitude toward all things alleged to be paranormal or supernatural, takes issue with the notion of such phenomena as well, often employing the same arguments and rhetorical strategies as The Skeptic’s Dictionary.

In short, the difference between the paranormal and the supernatural lies in whether one is a materialist, believing in only the existence of matter and energy, or a dualist, believing in the existence of both matter and energy and spirit. If one maintains a belief in the reality of the spiritual, he or she will classify such entities as angels, demons, ghosts, gods, vampires, and other threats of a spiritual nature as supernatural, rather than paranormal, phenomena. He or she may also include witches (because, although they are human, they are empowered by the devil, who is himself a supernatural entity) and other natural threats that are energized, so to speak, by a power that transcends nature and is, as such, outside or beyond the universe. Otherwise, one is likely to reject the supernatural as a category altogether, identifying every inexplicable phenomenon as paranormal, whether it is dark matter or a teenage werewolf. Indeed, some scientists dedicate at least part of their time to debunking allegedly paranormal phenomena, explaining what natural conditions or processes may explain them, as the author of The Serpent and the Rainbow explains the creation of zombies by voodoo priests.

Based upon my recent reading of Tzvetan Todorov's The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to the Fantastic, I add the following addendum to this essay.

According to Todorov:

The fantastic. . . lasts only as long as a certain hesitation [in deciding] whether or not what they [the reader and the protagonist] perceive derives from "reality" as it exists in the common opinion. . . . If he [the reader] decides that the laws of reality remain intact and permit an explanation of the phenomena described, we can say that the work belongs to the another genre [than the fantastic]: the uncanny. If, on the contrary, he decides that new laws of nature must be entertained to account for the phenomena, we enter the genre of the marvelous (The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre, 41).Todorov further differentiates these two categories by characterizing the uncanny as “the supernatural explained” and the marvelous as “the supernatural accepted” (41-42).

Interestingly, the prejudice against even the possibility of the supernatural’s existence which is implicit in the designation of natural versus paranormal phenomena, which excludes any consideration of the supernatural, suggests that there are no marvelous phenomena; instead, there can be only the uncanny. Consequently, for those who subscribe to this view, the fantastic itself no longer exists in this scheme, for the fantastic depends, as Todorov points out, upon the tension of indecision concerning to which category an incident belongs, the natural or the supernatural. The paranormal is understood, by those who posit it, in lieu of the supernatural, as the natural as yet unexplained.

And now, back to a fate worse than death: grading students’ papers.

My Cup of Blood

Anyway, this is what I happen to like in horror fiction:

Small-town settings in which I get to know the townspeople, both the good, the bad, and the ugly. For this reason alone, I’m a sucker for most of Stephen King’s novels. Most of them, from 'Salem's Lot to Under the Dome, are set in small towns that are peopled by the good, the bad, and the ugly. Part of the appeal here, granted, is the sense of community that such settings entail.

Isolated settings, such as caves, desert wastelands, islands, mountaintops, space, swamps, where characters are cut off from civilization and culture and must survive and thrive or die on their own, without assistance, by their wits and other personal resources. Many are the examples of such novels and screenplays, but Alien, The Shining, The Descent, Desperation, and The Island of Dr. Moreau, are some of the ones that come readily to mind.

Total institutions as settings. Camps, hospitals, military installations, nursing homes, prisons, resorts, spaceships, and other worlds unto themselves are examples of such settings, and Sleepaway Camp, Coma, The Green Mile, and Aliens are some of the novels or films that take place in such settings.

Anecdotal scenes--in other words, short scenes that showcase a character--usually, an unusual, even eccentric, character. Both Dean Koontz and the dynamic duo, Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, excel at this, so I keep reading their series (although Koontz’s canine companions frequently--indeed, almost always--annoy, as does his relentless optimism).

Atmosphere, mood, and tone. Here, King is king, but so is Bentley Little. In the use of description to terrorize and horrify, both are masters of the craft.

Innovation. Bram Stoker demonstrates it, especially in his short story “Dracula’s Guest,” as does H. P. Lovecraft, Edgar Allan Poe, Shirley Jackson, and a host of other, mostly classical, horror novelists and short story writers. For an example, check out my post on Stoker’s story, which is a real stoker, to be sure. Stephen King shows innovation, too, in ‘Salem’s Lot, The Shining, It, and other novels. One might even argue that Dean Koontz’s something-for-everyone, cross-genre writing is innovative; he seems to have been one of the first, if not the first, to pen such tales.

Technique. Check out Frank Peretti’s use of maps and his allusions to the senses in Monster; my post on this very topic is worth a look, if I do say so myself, which, of course, I do. Opening chapters that accomplish a multitude of narrative purposes (not usually all at once, but successively) are attractive, too, and Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child are as good as anyone, and better than many, at this art.

A connective universe--a mythos, if you will, such as both H. P. Lovecraft and Stephen King, and, to a lesser extent, Dean Koontz, Bentley Little, and even Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child have created through the use of recurring settings, characters, themes, and other elements of fiction.

A lack of pretentiousness. Dean Koontz has it, as do Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, Bentley Little, and (to some extent, although he has become condescending and self-indulgent of late, Stephen King); unfortunately, both Dan Simmons and Robert McCammon have become too self-important in their later works, Simmons almost to the point of becoming unreadable. Come on, people, you’re writing about monsters--you should be humble.

Longevity. Writers who have been around for a while usually get better, Stephen King, Dan Simmons, and Robert McCammon excepted.