copyright 2008 by Gray L. Pullman

Animals can be affectionate, loyal, and companionable. They can be amusing, amazing, and beautiful. They can work hard on our behalf, and even help to rescue people stranded in the wilderness or fight off would-be attackers, robbers, rapists, and murderers. Well, maybe not goldfish so much. On the other hand, they can also be cunning, ferocious, wild, dangerous, and deadly. Unless one of the friendly sort is going to end up first going mad and then going for the throat, however, as Cujo does, or become a victim of the monster, whatever it is, it’s not likely to be of much use to the horror writer, unless the author happens to be Dean Koontz, and loves dogs more than he does Greta (his wife). California has passed a law, it seems, that anyone who lives in Newport Beach, is a novelist, has a golden retriever, and is married to a woman named Greta who willingly takes second place to the dog must include at least one canine character in every novel he writes, and the dog must be above reproach, even if his or her master is not. For others who write in the genre, the fierce and ferocious--and, often, the biggest--animal is more likely to earn a spot in the story’s cast of characters.

In horror fiction, as in (from some men’s standpoint, but seldom women’s) breasts, generally, the bigger, the better. In another post, concerning “

The Underbelly of the Bug-eyed Monster Movie,” we’ve already discussed some movies that feature big, bug-eyed monsters (hence the title of that particular post). Quite a few movies, especially in the past, featured such villains, as some do today, and novels, of course, and short stories (and some narrative poems, such as

Gilgamesh,

The Odyssey, and

Beowulf) too, for that matter) feature giant animals as their monsters of choice. One of the ones that started it all, as far as novels are concerned, is H. G. Wells’

The Food of the Gods, in which a mad scientist develops a food additive that’s even better--way better, in fact--than Wonder Bread in developing strong bones and bodies or whatever Wonder Bread develops. The formula’s even better than Ovaltine!

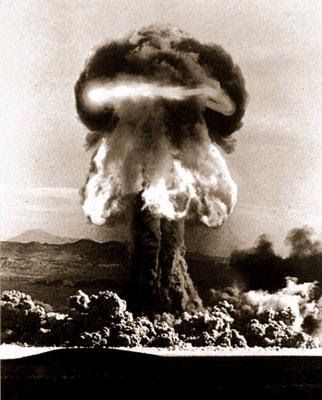

Stories like these usually relied upon the past (dinosaurs), undiscovered countries or lands of the lost (dinosaurs) or mad scientists (giant experimental plants and animals), atomic radiation (giant plants and animals) or extraterrestrial visitations (alien animals) instead of central casting to supply these threats. However, they needn’t have gone to such trouble or looked so far. Nature, right here and right now, supplies writers with real-life giant animals. True, some are more frightening than others, but, if one is, like Stephen King, willing to gross out if he can’t scare a reader, what some of these giants may lack in the fright department they compensate for in the disgusting department.

Here are a few of the more repulsive, sometimes frightening alternatives Mother Nature has in stock at the moment:

- Camel spiders

- Giant catfish

- Giant rats

- Goliath beetles

- Goliath frogs

Camel spiders anesthetize people and then eat them alive. That’s what some American veterans returning from duty in Iraq, the home of the infamous spiders, claimed, anyway--who’d escaped such a fate--but that was an exaggerated contention in several ways. First, the camel spider isn’t really a spider at all. It’s a solpudgid, which is an arachnid, all right, just not one of the spider family. (Other non-spider arachnids include scorpions, mites, ticks, and Peter Parker.) As a solpudgid, the misnamed camel spider has no venom with which to poison (or even anesthetize) anyone, nor does it have a system by which it could deliver such a toxin, even if it had one to deliver. Still, the camel spider

looks diabolical, even deadly, and, in horror fiction, appearances go a long way. The writer can always make up the facts as he or she goes along. If the author wants anesthetizing, or even poisoning, spiders, the author can and will have them. A good writer, especially a writer of horror fiction, never lets the facts get in the way of a good monster.

It might seem that the bewhiskered catfish would make an unlikely horror monster. If there wasn’t at least a glimmer of evil in its lidless, cold eyes, though, do you think it would have come to the attention of so august a body as the

National Geographic Society, the same group who showed bare-breasted African women to the innocent schoolboys of 1950 America? Just look at this sucker! It’s nine feet long, and, according to The Society, as its members in good standing are allowed to call it, this fish is “as big as a grizzly bear,” and “tipped the scales at 646 pounds.” This variety of potential cat food is one of “the species known as the Mekong giant catfish.” Put a few teeth inside it, and it could be the next piranha, super-sized.

Africa’s Goliath frog grows to a length of thirteen inches and can weigh as many as seven pounds!

Its yuck factor is correspondingly great for anyone who has frog fear, which, as it turns out, may be more people, male and female, than one thinks. It can’t quite leap tall buildings in a single bound, but it can cover a distance of twenty feet in a single jump. It can live for fifteen years, so it’s capable of revenge, like Grendel’s mother. It lives in Africa, or, more specifically, Cameron’s Sanaga basin. People eat it, rather than the other way around (so who’s the

real monsters?) or is sold to a zoo, where, usually, it doesn't do well. However, no self-respecting horror story writer would let a frog of this size go to waste as a potential peril to humankind. No way! Instead, like the non-poisonous, non-carnivorous, non-spider camel spiders, in horror fiction, these babies are going to be depicted as venomous, flesh-eating monsters that, having reproduced faster than their normal rate, for some reason having to do with human stupidity and/or greed, are now threats to humans, unable to subsist any longer on lesser animals such as the rhinoceros, hippopotamus, and elephant.

Would a story featuring three-foot-long rats be scary?

Duh! Stories involving rats only the size of puppies are frightening; a film or a novel featuring rats the size of Garfield or Odie would be terrifying (bigger generally is scarier). There’s just one thing wrong with such a scenario. Nobody would buy the existence of a rat that big, right? Wrong. The ones in H. G. Wells’ novel,

The Food of the Gods, were even bigger, and, besides, there really are three-foot-long rats, just not in your neighborhood--at least, not yet. Of course, there’s no reason that a character in a horror story couldn’t legally (or illegally) import some from New Guinea’s Foja Mountains or they couldn’t be procured by a zoo (or even created in a scientific lab). According to Smithsonian Institution scientist

Kristofer Helgen, “"The giant rat,” which weighs up to three pounds, “is about five times the size of a typical city rat," and has no fear of humans.

Another giant among us is the Goliath beetle, which measures about five inches (huge for a bug). It also lives in Africa, and eats human flesh. (Not really. They eat tree sap and fruit in the wild or cat food or dog food in captivity.) They sound like helicopters when they fly, because their bodies are heavily armored. They don’t bother people, but, because humans are naturally squeamish concerning creepy crawlies, they could, especially if they could be induced to swarm for the camera, be pretty good monsters. A writer would probably want to mutate them, though, so they could be transformed into carnivores. That way, they could prefer people meat to Tender Vittles or Kimbles ’n Bits.

Many people would have thought that giant animals, with a few exceptions, such as whales, elephants, and ostriches, are a thing of the past--the distant, prehistoric past--when dinosaurs roamed the planet. The discovery of new giants among us suggests that this is not true.

Over four hundred new species have been discovered on Borneo alone since 1996, and Madagascar and South America, as well as the ocean, have yielded others. In

King Kong, Carl Denham had to go to the uncharted (that is, imaginary) Skull Island to discover the lost world of the giant ape and surviving dinosaurs, but, with the dicovery of new species, including giants, seemingly every other day, horror writers may need to go no farther than Madagascar, the African continent, Japan, or South America to encounter real, living, breathing monstrosities. Who knows? There may even be one in

your backyard, and it may be hungry.

Meanwhile, we can continue to turn to the pages of horror novels and science fiction stories to read about them or watch them wreck havoc on the big screen.

Update (3/21/08)

Over the past year, scientists, poking around in the world’s oceans and rain forests, have announced their discoveries of several new species of animals and of some giants among known species. Among the latest discoveries are giant macroptychaster starfish, measuring two feet across, which were located in New Zealand’s Antarctic Ocean. Other newly found giants include an 11-foot, 844-pound white shark, a 990-pound colossal squid, an Echizen jellyfish larger than a man, and a 23-pound lobster. Scientists aren’t the only ones to encounter these giants. On his farm near Eberswalde, Germany, Karl Szmolinsky breeds 20-pound giant rabbits, like the one he’s holding. More and more, the everyday world is catching up with the imaginary giant creatures of horror, fantasy, and science fiction literature. No doubt, some of these beasties will be tomorrow fiction’s featured creatures, although not, perhaps, the giant bunnies.

“Everyday Horrors: Giant Animals” is part of a series of “everyday horrors” that will be featured in Chillers and Thrillers: The Fiction of Fear. These “everyday horrors” continue, in many cases, to appear in horror fiction, literary, cinematographic, and otherwise.