Sunday, October 13, 2013

Marvelous Ideas

Monday, August 2, 2010

Horror Comics

Not only Stephen King, but also Joss Whedon and many other writers of horror fiction cite horror comic books as inspirational to their own work, especially during such writers’ earlier years.

As a youngster, I must confess that I, too, enjoyed these tawdry, garish periodicals. Sold alongside comics devoted to “funny animals,” superheroes, crime detection, Western heroes, romance, and even classic literature, horror comics were the bad boys of juvenilia, the ones that even kids knew weren’t all that respectable and tended to keep separate from their collections of DC and Marvel.

Horror comics were popular, though, no doubt about it, and with millions of others besides King and Whedon. What made them so were blood and gore and monsters, depicted in all their ghastly glory, of course, and the bizarre and macabre stories they told, but, more than anything else, it was the reader’s own imagination that chilled and thrilled him or her (mostly him; girls seemed to prefer romance and comedy titles).

The titles suggested the appeal of these comics: Adventures into Weird Worlds, Astonishing Tales of the Night, Baffling Mysteries, Terror Tales, Weird Monsters Unleashed, Monster Hunters, Tales of Terror, Chamber of Chills, The Haunt of Fear, Stories to Hold You Spellbound, Startling Terror, Weird Chills, Worlds of Fear: these narratives, told as much, maybe more, in pictures than in words, promised to transport the reader into new “worlds” that were “weird,” “astonishing,” “baffling,” and full of horror, suspense, and fear. Gone would be the mundane world of school, chores, church, sibling nuisances and rivals, bullies, and parents telling one what to do, to be replaced with wonder, mystery, adventure, chills, and thrills.

Like many others, horror writers have developed rationales for why people enjoy being scared out of their wits, probably in response to challenges from literary critics and others, demanding a justification for such fare beyond the “art for art’s sake” line. King offers an Aristotelian argument, contending that horror fiction exorcises the demons within the reader by letting him or her (mostly him) play the role of the monster or, at least, seeing the effects of the monstrosity that he himself often feels within, when it is permitted to go unrestrained. They are pleasant, perhaps, all that blood and all those guts, but they are cathartic as well. There is some truth, perhaps, in this Aristotelian explanation.

Whedon also offers a justification for his work, which, more often than not, is steeped in horror. His rationale for horror is along the lines of the argument that Bruno Bettelheim advances in The Uses of Enchantment:

I think there’s a lot of people. . . who say we must not have horror in any form, we must not say scary things to children because it will make them evil and disturbed. . . . . That offends me deeply because the world is a scary and terrifying place, and everyone is going to get old and die, if they’re that lucky. To set children up to think that everything is sunshine and roses is doing them a great disservice. Children need horror because there are things they don’t understand. It helps them to codify it if it is mythologized, if it’s put into the context of a story, whether the story has a happy ending or not. If it scares them and shows them a bit of the dark side of the world that is there and always will be, it’s helping them out when they have to face it as adults (The Monster Book, viii).There is some truth, too, perhaps, in this explanation.

In previous posts, I have offered my own ideas concerning the reasons for the appeal of horror fiction, so I won’t repeat them here. For those who may be interested, these essays are available in Chillers and Thrillers' massive, ever-growing archives.

Back to the topic at hand, though: horror comics.

As anyone who has ever seen a tyke cowering behind the leg of his or her mother knows, for children, strangers are threatening. This is interesting, I think, because the same toddler who shrinks from a stranger will pick up a snake without the qualms that many an adult shows in handling serpents. As boys, my brothers and I frequently carried box turtles, garter snakes, and frogs with us in our pockets and sought to snare salamanders near a neighbor’s creek, although strangers were regarded as likely demons in human guise. Although, in more recent times, xenophobia has become increasingly politically incorrect, the fear of strangers seems innate, or inborn. Can nature or God be wrong?

Certainly not from the viewpoint of the cowering toddler--or of horror comics. The monster, especially when it is reptilian, insect (the word is both a noun and an adjective, for those who haven’t studied entomology or, for that matter, etymology), or alien (as in extraterrestrial), frequently represents the other who is not only “other” but who is also foreign and, therefore, unknown. Those about whom we have little, if any, knowledge are regarded as threats (it’s better to be safe than sorry) until we learn their intentions and their hearts. This may be a politically incorrect stance, but it’s helped us to survive for millennia and isn’t likely to go away any time soon. Besides, whether the monster in horror comics is equipped with tentacles, a seaweed mustache and beard, bony plates, horns, claws, insect parts, wings, or all of the above or is more human, but repulsive (an animated skeleton, for example, or a rotting, but somehow still living, corpse), it’s apt to be just as terrifying, unpredictable, and dangerous as the children within us have imagined strangers may be.

Like most subjects, horror fiction is divisible into stories about persons places, and things.

If the monster is the person, the setting is the place, and unfamiliar places are regarded with the same wary mistrust as strangers. Who knows what may lie waiting to ambush us in the dark recesses of an underground cave; among the thick, tall trees of an ancient forest; at the bottom of the murky sea; on far-flung, alien planets; or in any of the other fantastic and mysterious worlds promised in the titles of many horror comics and suggested in the artwork that adorns these periodicals’ covers and the pages within?

Things (or artifacts) also appear in horror comics. As anyone who’s watched the hit Syfy TV series Warehouse 13 knows, such artifacts are everywhere, and many are dangerous in the extreme--and Secret Service agents Myka Bering and Peter Lattimer haven’t located and stored them all for safekeeping yet. There are more, maybe many more, out there, waiting, as it were, to injure and maybe even kill the unsuspecting and the uniformed.

The themes of horror comics are often as simple and straightforward as the tales themselves that these publications tell: bad things happen to those who are in the wrong place at the wrong time, a little beauty of the feminine kind can be a dangerous thing (it tends to attract actual monsters as well as human wolves), a little beauty of the feminine kind can be a dangerous thing (it can get a guy killed), beauty (feminine or otherwise) can be seductive in a bad way, curiosity can kill more than just the cat, there’s no age restriction on potential victims as far as homicidal maniacs are concerned, a trusted and seemingly harmless friend (such as a toy) can turn on one, isolating oneself from the rest of the group is dangerous unless one is a lone wolf, religious faith (often in the shape of a cross) can deliver a believer from evil (and otherwise certain death), there are “more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in our philosophy” (dear Horatio), and creatures of the night are often in need of dental care and a good manicure. Horror comics tell cautionary tales, and there are quite a few to be told. Both King and Whedon admit that just about everything scared or scares them; the same is true of children (and many adults), as horror comic writers and illustrators were fully aware.

A few covers surprise the reader with visual allusions to the occult or classic literature (or, at least, classics of horror). Doorway to Nightmare 2, for example, includes the tarot deck’s Devil card, which features an image of a demon that looks suspiciously like Baphomet, and Frankenstein’s monster, Dracula., and even Cthulhu are frequent guest stars in horror comics.

As mentioned, boys more than girls, read horror comics, and the creators of these publications were aware of the demographics of their readers, which explains not only the sexism of the femme fatale and the seductive siren characters that frequent the pages of horror comics’ storylines but also the scantily clad beauties who grace their covers (usually in the company of a menacing monster). Even when climate or weather or atmospheric conditions do not warrant her doing so, the damsel in distress is likely to be clad in nothing more than a short, clinging dress with a low, low, low-cut neckline; a bikini; or, in some cases, only her birthday suit. Monsters had good taste in (and a hearty appetite for) women, and the imperiled ladies, no doubt, aroused the chivalry (among other things) in the boys who read such fare.

Moreover, the covers seem to issue a challenge to their adolescent male readers: Here is a lady in distress; are you man enough to rescue her? By introducing just a hint of sexuality, horror comics also seemed to prepare boys for a role that they would play as men that has nothing to do with slaying monsters, except that, for boys, women are monsters, an alien species with cooties that may be glamorous and alluring but one that is also something strange and unknown and, therefore, to be feared, until, that is, the humanity beneath the imagined scales and behind the make-believe glowing eyes and razor fangs can be rescued, accepted, known, and, finally, cherished, not only as human but as, indeed, one’s better half.

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

Imagining Hell

The Christian Hell is named for the Norse goddess who ruled the Aesir’s underworld, Hel. The ancient Israelites did not have a hell in the sense that their underworld, Sheol, was a place of eternal punishment. Sheol was much more like the ancient Greeks’ Hades or, for that matter, the Norsemen’s Hel, a place of shadowy existence wherein ghostly “shades” went about the business of postmortem existence. Dante imagined his own hell, in The Inferno, and, for the atheistic French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre, hell was “other people.” Perhaps the closest place to hell in the modern world is prison--or, possibly, Detroit, Michigan. (Michael Moore would have us think hell on earth is neighboring Flint.)

Hell is the garbage dump of eternity. It’s a cosmic prison. It’s the place of “wailing” and the “gnashing of teeth,” wherein the “fire is not quenched” and the “worm dieth not.” It’s the place that Mark Twain would go for “company,” preferring heaven for its “scenery.” For some, hell is a state of mind or a state of the soul, the opposite of the “kingdom of heaven,” which Jesus said “is within you.”

If anyone should be able to imagine hell, it is the writer of horror fiction. How to begin such a--well, hellish--task? Picture the condemned, which is to say, the types of individuals whose lifestyles or behaviors seem to warrant condemnation, banishment, and/or punishment, not just for a day, but for all eternity. Characterize them. What are the attributes of their personalities? What attitudes do they express? What do they believe? What do they imagine? What do they fear? What hopes, if any, do they have? What do they love, better than God or mankind--in other words, what idol do they worship? What is their besetting sin, and what lesser, but related, sins are associated with it, and why? What do they do all day?

Having imagined the denizens of your hell, picture the lay of the land, or “scenery,” that would be appropriate for such residents. Are there mountains and valleys, molten seas, volcanoes in endless eruption, frozen wastelands, deserts, underworlds within--or below--underworlds? Is your hell multileveled like Dante’s Inferno? Perhaps your hell is unlike anything familiar to mortal men and women, something like, but unlike, the mystical worlds of Marvel Comics’ Dr. Strange?

When you’ve finished peopling and landscaping your inferno, ask yourself what symbolic significance the landscape’s features have. In doing so, you might ask yourself what the images of the Christian hell represent figuratively. What is the symbolic significance of the “fire [that] is not quenched” and the “worm [that] dieth not”? Apply the same process of analysis and interpretation to the images of your own hell.

Remember this, too: now that you’ve gone to all the time and trouble of imagining a hell of your own, your stories may sometimes take place in this infernal abode, or its residents may occasionally escape and visit the world of humanity. Angels, by definition, are, after all, messengers of God, and, in the Bible, even “fallen angels,“ or demons, do sometimes visit--and afflict--ordinary men and women and, if The Exorcist is any guide to infernal behavior, children, too. Their chief, Satan, had the audacity to tempt even Christ! What “message” might one of your accursed bring to one or more of your story’s characters?

In another application of your hell, the residents may be seen as “inner,” rather than as outer demons--as psychological defects and disorders, or diseased elements of the soul, with lives of their own, so to speak, along the lines of BTK’s “Factor X” or Ted Bundy’s “entity.” Of course, they may also be both inner and outer demons, as any particular story’s plot dictates. By imagining a hell of your own, you will be more apt to put your own spin on the action you narrate, making an original contribution, perhaps, to the iconography of the damned and offer a few new insights into the hellish behavior of the demonic soul.

For those who are interested in more information about hell, “Hell in the Old Testament” offers quite a bit.

Tuesday, August 5, 2008

Nothing Gets Between a Monster and Its Genes

Why did you throw the jack of hearts away? It was the only card in the deck I had left to play.

-- The Doors

As far as I know, it was Stan Lee of Marvel Comics who introduced comic book readers to the idea of genetic mutation as the cause of superhuman traits that could convert an otherwise normal human being into a godlike character who could use his or her powers for good or evil. In doing so, Lee inserted a joker into the deck of fate. (Actually, since quite a few of the superhuman powers of Marvel’s superheroes and villains were the results of such mutations, Lee inserted almost as many jokers into the deck as there were regular, or “normal” cards.) Since there have been a rash of motion pictures based upon Marvel Comics (and, for that matter DC Comics) of late, many of the characters in which possess powers courtesy of various genetic mutations, it seems unnecessary to review these powers. For those who are unfamiliar with how the Marvel Comics’ powers-by-genetic-mutation technique works, a brief summary is in order. According to Marvel, the Celestials, an extraterrestrial race, visited the Earth a million or so years ago for the express purpose of monk eying with human deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), implanting a substance, the X-Gene, which facilitated beneficial genetic mutations in the implanted hosts, resulting, in more extreme cases, in such characters as those who swelled the ranks of the The Uncanny X-Men (the first issue of which appeared in (1963) and the Brotherhood of Mutants. For years, this was Marvel Comics’ favorite explanation for superheroes’ and villains’ great powers, explaining the abilities of such characters as Apocalypse, Beast, Cyclops, Iceman, Marvel Girl, Professor X, Storm, Wolverine, and many others. Collectively, such characters, in the Marvel universe, are also known as homo superior.

What have they done to the Earth? What have they done to our fair sister? Ravaged and plundered and ripped her and but her, Stuck her with knives in the side of the dawn, Tied her with fences and dragged her down. . . .

-- The Doors

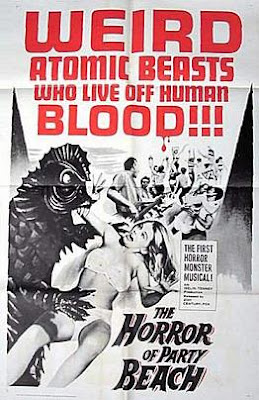

Even before Lee introduced genetic mutations as a cause of characters’ special effects, so to speak, horror fiction monsters were spawned, as it were, as a result of genetic mutations. (Most appeared in decidedly bad--no, make that terrible--B films.) Among such creatures are the sea monsters of The Horror of Party Beach (1964) (human skeletons radiated by atomic waste that leaks from an undersea drum, a peril of humans’ disdain for ecological purity); the monster of Godzilla (1954) (an undersea creature that had an origin identical to the monsters of Party Beach); The Being (1983) (a monster who was spawned by the wastes in a disposal dump); Creatures from the Abyss (1994) (teen love makers, whose decision to make out aboard an abandoned yacht equipped with a bio lab causes them to become infected with radioactive plankton); C.H.U.D. (1984) (people become monsters as a result of toxic waste dumped in the Big Apple’s sewers); It’s Alive (1974) (a mutant baby is sought by the authorities, who don’t intend to nurture it); and many others.

Even before Lee introduced genetic mutations as a cause of characters’ special effects, so to speak, horror fiction monsters were spawned, as it were, as a result of genetic mutations. (Most appeared in decidedly bad--no, make that terrible--B films.) Among such creatures are the sea monsters of The Horror of Party Beach (1964) (human skeletons radiated by atomic waste that leaks from an undersea drum, a peril of humans’ disdain for ecological purity); the monster of Godzilla (1954) (an undersea creature that had an origin identical to the monsters of Party Beach); The Being (1983) (a monster who was spawned by the wastes in a disposal dump); Creatures from the Abyss (1994) (teen love makers, whose decision to make out aboard an abandoned yacht equipped with a bio lab causes them to become infected with radioactive plankton); C.H.U.D. (1984) (people become monsters as a result of toxic waste dumped in the Big Apple’s sewers); It’s Alive (1974) (a mutant baby is sought by the authorities, who don’t intend to nurture it); and many others.

Why the popularity of genetic mutations as an explanation for the acquisition of superhuman or monstrous abilities? There seem to be several reasons:When the still sea conspires an armor And her sullen and aborted Currents breed tiny monsters True sailing is dead.

--The Doors

- When horror films and Marvel Comics introduced the idea, genetic mutation as the result of changes to an organism’s DNA was relatively new, or cutting edge, as was the idea for genetic engineering. However, eugenics was already a well-known concept and attempts at engineering an ideal race were tried by mad scientists during the years of Nazi Germany. (The concept of what constitutes such a race--and, indeed, the very idea of a “master race”--is, or can be, in itself a monstrous notion and involves the same hubris that was demonstrated by Victor von Frankenstein and Dr. Moreau in earlier times.) Writers are always looking for new ideas because new ideas, in and of themselves, are intriguing.

- The origins of good and evil tend to be limited to such causes as divine creation, demonic possession or manipulation of human beings, madness, improper behavior (sin, crime, or anti-social conduct), birth defects, extraterrestrial intervention in human affairs, scientific and technological manipulations of nature and human nature, and the like. When a new cause for good or evil (and not just abilities) is unearthed, it’s apt to be popular and persistent among authors, especially of fantasy, science fiction, and horror, including writers of comic books that involve or are based upon such genres.

- Genetic mutations are real! They actually happen in nature and can be engineered in scientific labs by real-life “mad scientists.” Of course, any scientist worth his or her weight in neutronium will tell one that such mutations, rather than benefiting an organism, are more likely to have a negative, or even fatal, effect upon it. That’s a small detail often overlooked by comic book, fantasy, science fiction, and horror writers, although some do capitalize upon this fact, using genetic mutations as a way of effecting madness or physical deformity that, in return, has monstrous results.

- Genetic mutations that result from scientific and technological manipulations of nature replace miracles as a means of effecting changes to DNA and, therefore, to human nature and behavior, allowing human beings, in their arrogance, to wrest creation from the creator, putting people in charge of a world they never made but one that they are hot to remake in their own image and likeness. From a religious point of view, such arrogance, or pride, is blasphemous and can be expected to result is sure punishment. From a secular point of view, such hubris is presumptuous and, perhaps, premature, and will likely bring about, in its results, its own penalty, for, after all, it’s nice to fool with Mother Nature and it’s even worse to fool around with her.

He was a monster, dressed in black leather; She was a princess, Queen of the highway. -- The Doors

Saturday, May 17, 2008

Going Through the Motions, or The Physics of Fiction

- An object at rest remains at rest, or if moving remains moving in a straight line if no external forces act upon it.

- If an external force is applied, the object’s motion will change in either magnitude or direction, and the rate of change of the motion (its acceleration) when multiplied by the object’s mass is equal to the applied force.

- For every force applied to an object there is an equal and opposite force exerted back by the object (24-25).

Let’s apply these laws of motion to the horror story plot (or, for that matter, any other type of plot).

According to Gustav Freytag, an incident in the story’s plot sets everything that follows it into motion. This incident, called the inciting moment, is like a spark that starts a fire or, in terms of Newton’s laws of motion, it is the external force that changes the plot-as-object’s motion, causing it to take a new direction. Were it not for the inciting moment, the plot would continue forward, in a straight line, so to speak, rather than changing direction as it begins its upward climb which commences what Freytag calls the plot’s rising action.

The third law of motion is also useful as a means of envisioning what writers, literary critics, and readers call conflict, for it is the “force applied” by the protagonist to the antagonist, or “object,” countered by the “equal and opposite force exerted back” by the antagonist that balances the story’s action (at least until the turning point, a second inciting moment of sorts, which intervenes to set the plot off in a new, downward direction, as it were, Freytag’s falling action.

As Kakalios points out, the second law of motion (“If an external force is applied, the object’s motion will change in either magnitude or direction, and the rate of change of the motion (its acceleration) when multiplied by the object’s mass is equal to the applied force”) can be represented by the mathematical formula F = ma, wherein F = force, m = mass, and a = acceleration (25). (Acceleration differs from velocity, Kakalios reminds his readers. The former refers to the change in speed over time, whereas the latter refers to the change in speed over distance [30].) Mass is simply a measure of how many atoms make up an object. A piece of plastic is made up of relatively few atoms, whereas lead is comprised of many more atoms, packed, as it were, in an equal amount of space. The more atoms-per-space (mass) and the greater the rate of acceleration, the more force results. In terms of story plotting, we mentally replace atoms with narrative incidents (or, in description, perhaps with action verbs and shorter sentences). The more incidents, action verbs, and sentences we “pack” into a passage, the greater its force, or narrative effect, upon the reader. It seems that Edgar Allan Poe has something similar to this concept, minus the physical laws of motion, in mind, when he argues, in “The Philosophy of Composition,” that a shorter story, especially one that can be read in “a single sitting,” without interruption, has a greater effect upon its readers than a longer story which is, in effect, simply a series of shorter stories told successively and related to one another through cause and effect. To make a story more horrifying, speed up the action (writing action verb-packed short sentences in a rapid-fire series of narrative incidents); to slow the pace and the story’s effect (horror), slow down the same process.

It seems that, understood figuratively, Newton’s laws of motion apply to plotting horror fiction (and other literary genres) as much as they do to physical and mechanical motion.

Source cited

Kakalios, James. The Physics of Superheroes. New York: Gotham Books, 2005.

Saturday, February 23, 2008

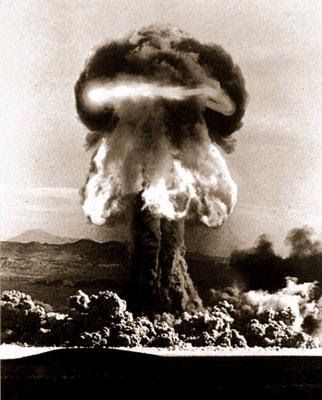

Everyday Horrors: The Atomic Bomb

When we see or hear the word “bikini,” we tend to think of--well, not death and destruction, certainly. However, it was upon the Bikini atoll, in the Pacific Ocean, that the first several nuclear bombs were tested. After detonating the bomb, the U. S. government relocated natives back to the atoll, from which they’d been evacuated, but the levels of radioactivity within their bodies suggested that they should be relocated again, so they were moved to Kili island, where they remain, wards of the federal government.

It was a Bikini atoll test that awakened the Japanese monster Godzilla. However, the U. S. was involved in far more sinister activities than those precipitated by the awakening of the fictitious Godzilla.

One of these activities was Project 4.1, a medical experiment that the government conducted in secret upon Marshall Island residents who had been exposed to radioactive fallout as a result of the government’s Castle Bravo nuclear test, which took place upon the Bikini atoll. The experiment, which began within a week of the Castle Bravo test, was known, officially, as “Study of Response of Human Beings Exposed to Significant Beta and Gamma radiation due to Fall-Out from High Yield Weapons.” (The powers of many of the Marvel Comics characters, including the Hulk and Spider-man, are results of radioactive experiments. Perhaps Stan Lee knew more than he’s saying?)

The Department of Energy stated the threefold purpose of the project: “(1) evaluate the severity of radiation injury to the human beings exposed, (2) provide for all necessary medical care, and (3) conduct a scientific study of radiation injuries to human beings.” The study showed significant effects from the Marshallese’s exposure to the radioactive fallout, including hair loss, skin damage (“raw, weeping lesions”), miscarriages, stillbirths, cancer, and neoplasms.

As bad as the fate of the test site’s human guinea pigs was, that of the Japanese at Nagasaki and Hiroshima were even worse. Those victims of the atomic bombs designated as Little Boy (which took out Hiroshima on August 6, 1945) and Fat Man (which took out Nagasaki on August 9, 1946), who survived the attack experienced severe burns, radiation sickness, and a variety of diseases, including cancer. As many as 140,000 people in Hiroshima and 80,000 in Nagasaki were killed by the explosion of the bomb. The cities themselves were leveled, with only a few, burned-out structures remaining. Had Japan not surrendered, ending World War II, the U. S. had planned to drop several more atomic bombs on the island nation, as more of the weapons were in production and were expected to be completed during the next few months.

The atomic bomb was the product of the Manhattan Project, headed by J. Robert Oppenheimer.

During the 1950’s and 1960’s, many B horror films were made that featured monsters (often Bug-eyed Monsters) created by the effects of the atomic bomb or radiation in general, including:

- Amazing Colossal Man, The

- Attack of the Giant Leeches

- Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, The

- Bride of the Monster

- Creature from the Black Lagoon, The

- Damnation Alley

- Day the Earth Caught Fire, The

- Day the earth Ended, The

- Fiend without a Face

- Godzilla

- Hills Have Eyes, The

- Incredible Shrinking Man, The

- It Came from Beneath the Sea

- Killer Shrews, The

- Omega Man, The

- Rocket Ship X-M

- Them!

- Airship Nine

- Alas, Babylon

- Amnesia Moon

- Arc Light

- Ashes Series

- Brother in the Land

- Canticle for Leibowitz, A

- Children of the Dust

- Chrysalids, The

- Commander-1

- Dark Tower Saga, The

- Dark December by Alfred Coppel

- Dark Mirrors

- Day They H-Bombed Los Angeles, The

- Dr. Bloodmoney, or How We Got Along After the Bomn

- Domain

- Doomday Wing

- Down to a Sunless Sea

- Dune

- Earthwreck!

- End of the World, The

- Farnham's Freehold

- Gate to Women's Country, The

- Hostage

- Last Children of Schewenborn, The

- Last Ship, The

- Level 7

- Light's Out

- Long Mynd, The

- Malevil

- Not This August

- On the Beach

- Outward Urge, The

- Postman, The

- Red Alert

- Resurrection Day

- Riddley Walker

- Pre-Empt

- Pulling Through

- School for Atheists, The

- Seventh Day, The

- Small Armageddon, A

- Solution T-25

- Swan Song

- Systemic Shock

- Road, The

- This Is the Way the World Ends

- This Time Tomorrow

- Tomorrow!

- Triton Ultimatum, The

- Warday

- When the Wind Blows

- Wild Shore, The

- World Set Free , The

- World Next Door, The

- Worldwar

- Z for Zachariah

- Zone, The

However, when one considers the U. S. government’s irresponsible testing and use of human guinea pigs, to say nothing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the films featuring monsters pale in comparison to the horrors unleashed by the feds. It’s as is, in seizing the power of God, humanity has become not divine, but demonic, a destroyer rather than a creator.

More horrible yet may be the proliferation of atomic weapons around the world. According to the Federation of American Scientists, these nations have nuclear weapons capabilities:

- China

- France

- India

- Israel

- North Korea

- Pakistan

- Russia

- United Kingdom

- United States

“Everyday Horrors: The Atomic Bomb” is the first in a series of “everyday horrors” that will be featured in Chillers and Thrillers: The Fiction of Fear. These “everyday horrors” continue, in many cases, to appear in horror fiction, literary, cinematographic, and otherwise.

Paranormal vs. Supernatural: What’s the Diff?

Sometimes, in demonstrating how to brainstorm about an essay topic, selecting horror movies, I ask students to name the titles of as many such movies as spring to mind (seldom a difficult feat for them, as the genre remains quite popular among young adults). Then, I ask them to identify the monster, or threat--the antagonist, to use the proper terminology--that appears in each of the films they have named. Again, this is usually a quick and easy task. Finally, I ask them to group the films’ adversaries into one of three possible categories: natural, paranormal, or supernatural. This is where the fun begins.

It’s a simple enough matter, usually, to identify the threats which fall under the “natural” label, especially after I supply my students with the scientific definition of “nature”: everything that exists as either matter or energy (which are, of course, the same thing, in different forms--in other words, the universe itself. The supernatural is anything which falls outside, or is beyond, the universe: God, angels, demons, and the like, if they exist. Mad scientists, mutant cannibals (and just plain cannibals), serial killers, and such are examples of natural threats. So far, so simple.

What about borderline creatures, though? Are vampires, werewolves, and zombies, for example, natural or supernatural? And what about Freddy Krueger? In fact, what does the word “paranormal” mean, anyway? If the universe is nature and anything outside or beyond the universe is supernatural, where does the paranormal fit into the scheme of things?

According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word “paranormal,” formed of the prefix “para,” meaning alongside, and “normal,” meaning “conforming to common standards, usual,” was coined in 1920. The American Heritage Dictionary defines “paranormal” to mean “beyond the range of normal experience or scientific explanation.” In other words, the paranormal is not supernatural--it is not outside or beyond the universe; it is natural, but, at the present, at least, inexplicable, which is to say that science cannot yet explain its nature. The same dictionary offers, as examples of paranormal phenomena, telepathy and “a medium’s paranormal powers.”

Wikipedia offers a few other examples of such phenomena or of paranormal sciences, including the percentages of the American population which, according to a Gallup poll, believes in each phenomenon, shown here in parentheses: psychic or spiritual healing (54), extrasensory perception (ESP) (50), ghosts (42), demons (41), extraterrestrials (33), clairvoyance and prophecy (32), communication with the dead (28), astrology (28), witchcraft (26), reincarnation (25), and channeling (15); 36 percent believe in telepathy.

As can be seen from this list, which includes demons, ghosts, and witches along with psychics and extraterrestrials, there is a confusion as to which phenomena and which individuals belong to the paranormal and which belong to the supernatural categories. This confusion, I believe, results from the scientism of our age, which makes it fashionable for people who fancy themselves intelligent and educated to dismiss whatever cannot be explained scientifically or, if such phenomena cannot be entirely rejected, to classify them as as-yet inexplicable natural phenomena. That way, the existence of a supernatural realm need not be admitted or even entertained. Scientists tend to be materialists, believing that the real consists only of the twofold unity of matter and energy, not dualists who believe that there is both the material (matter and energy) and the spiritual, or supernatural. If so, everything that was once regarded as having been supernatural will be regarded (if it cannot be dismissed) as paranormal and, maybe, if and when it is explained by science, as natural. Indeed, Sigmund Freud sought to explain even God as but a natural--and in Freud’s opinion, an obsolete--phenomenon.

Meanwhile, among skeptics, there is an ongoing campaign to eliminate the paranormal by explaining them as products of ignorance, misunderstanding, or deceit. Ridicule is also a tactic that skeptics sometimes employ in this campaign. For example, The Skeptics’ Dictionary contends that the perception of some “events” as being of a paranormal nature may be attributed to “ignorance or magical thinking.” The dictionary is equally suspicious of each individual phenomenon or “paranormal science” as well. Concerning psychics’ alleged ability to discern future events, for example, The Skeptic’s Dictionary quotes Jay Leno (“How come you never see a headline like 'Psychic Wins Lottery'?”), following with a number of similar observations:

Psychics don't rely on psychics to warn them of impending disasters. Psychics don't predict their own deaths or diseases. They go to the dentist like the rest of us. They're as surprised and disturbed as the rest of us when they have to call a plumber or an electrician to fix some defect at home. Their planes are delayed without their being able to anticipate the delays. If they want to know something about Abraham Lincoln, they go to the library; they don't try to talk to Abe's spirit. In short, psychics live by the known laws of nature except when they are playing the psychic game with people.In An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural, James Randi, a magician who exercises a skeptical attitude toward all things alleged to be paranormal or supernatural, takes issue with the notion of such phenomena as well, often employing the same arguments and rhetorical strategies as The Skeptic’s Dictionary.

In short, the difference between the paranormal and the supernatural lies in whether one is a materialist, believing in only the existence of matter and energy, or a dualist, believing in the existence of both matter and energy and spirit. If one maintains a belief in the reality of the spiritual, he or she will classify such entities as angels, demons, ghosts, gods, vampires, and other threats of a spiritual nature as supernatural, rather than paranormal, phenomena. He or she may also include witches (because, although they are human, they are empowered by the devil, who is himself a supernatural entity) and other natural threats that are energized, so to speak, by a power that transcends nature and is, as such, outside or beyond the universe. Otherwise, one is likely to reject the supernatural as a category altogether, identifying every inexplicable phenomenon as paranormal, whether it is dark matter or a teenage werewolf. Indeed, some scientists dedicate at least part of their time to debunking allegedly paranormal phenomena, explaining what natural conditions or processes may explain them, as the author of The Serpent and the Rainbow explains the creation of zombies by voodoo priests.

Based upon my recent reading of Tzvetan Todorov's The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to the Fantastic, I add the following addendum to this essay.

According to Todorov:

The fantastic. . . lasts only as long as a certain hesitation [in deciding] whether or not what they [the reader and the protagonist] perceive derives from "reality" as it exists in the common opinion. . . . If he [the reader] decides that the laws of reality remain intact and permit an explanation of the phenomena described, we can say that the work belongs to the another genre [than the fantastic]: the uncanny. If, on the contrary, he decides that new laws of nature must be entertained to account for the phenomena, we enter the genre of the marvelous (The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre, 41).Todorov further differentiates these two categories by characterizing the uncanny as “the supernatural explained” and the marvelous as “the supernatural accepted” (41-42).

Interestingly, the prejudice against even the possibility of the supernatural’s existence which is implicit in the designation of natural versus paranormal phenomena, which excludes any consideration of the supernatural, suggests that there are no marvelous phenomena; instead, there can be only the uncanny. Consequently, for those who subscribe to this view, the fantastic itself no longer exists in this scheme, for the fantastic depends, as Todorov points out, upon the tension of indecision concerning to which category an incident belongs, the natural or the supernatural. The paranormal is understood, by those who posit it, in lieu of the supernatural, as the natural as yet unexplained.

And now, back to a fate worse than death: grading students’ papers.

My Cup of Blood

Anyway, this is what I happen to like in horror fiction:

Small-town settings in which I get to know the townspeople, both the good, the bad, and the ugly. For this reason alone, I’m a sucker for most of Stephen King’s novels. Most of them, from 'Salem's Lot to Under the Dome, are set in small towns that are peopled by the good, the bad, and the ugly. Part of the appeal here, granted, is the sense of community that such settings entail.

Isolated settings, such as caves, desert wastelands, islands, mountaintops, space, swamps, where characters are cut off from civilization and culture and must survive and thrive or die on their own, without assistance, by their wits and other personal resources. Many are the examples of such novels and screenplays, but Alien, The Shining, The Descent, Desperation, and The Island of Dr. Moreau, are some of the ones that come readily to mind.

Total institutions as settings. Camps, hospitals, military installations, nursing homes, prisons, resorts, spaceships, and other worlds unto themselves are examples of such settings, and Sleepaway Camp, Coma, The Green Mile, and Aliens are some of the novels or films that take place in such settings.

Anecdotal scenes--in other words, short scenes that showcase a character--usually, an unusual, even eccentric, character. Both Dean Koontz and the dynamic duo, Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, excel at this, so I keep reading their series (although Koontz’s canine companions frequently--indeed, almost always--annoy, as does his relentless optimism).

Atmosphere, mood, and tone. Here, King is king, but so is Bentley Little. In the use of description to terrorize and horrify, both are masters of the craft.

Innovation. Bram Stoker demonstrates it, especially in his short story “Dracula’s Guest,” as does H. P. Lovecraft, Edgar Allan Poe, Shirley Jackson, and a host of other, mostly classical, horror novelists and short story writers. For an example, check out my post on Stoker’s story, which is a real stoker, to be sure. Stephen King shows innovation, too, in ‘Salem’s Lot, The Shining, It, and other novels. One might even argue that Dean Koontz’s something-for-everyone, cross-genre writing is innovative; he seems to have been one of the first, if not the first, to pen such tales.

Technique. Check out Frank Peretti’s use of maps and his allusions to the senses in Monster; my post on this very topic is worth a look, if I do say so myself, which, of course, I do. Opening chapters that accomplish a multitude of narrative purposes (not usually all at once, but successively) are attractive, too, and Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child are as good as anyone, and better than many, at this art.

A connective universe--a mythos, if you will, such as both H. P. Lovecraft and Stephen King, and, to a lesser extent, Dean Koontz, Bentley Little, and even Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child have created through the use of recurring settings, characters, themes, and other elements of fiction.

A lack of pretentiousness. Dean Koontz has it, as do Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, Bentley Little, and (to some extent, although he has become condescending and self-indulgent of late, Stephen King); unfortunately, both Dan Simmons and Robert McCammon have become too self-important in their later works, Simmons almost to the point of becoming unreadable. Come on, people, you’re writing about monsters--you should be humble.

Longevity. Writers who have been around for a while usually get better, Stephen King, Dan Simmons, and Robert McCammon excepted.