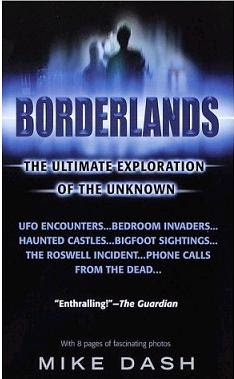

According to the flyleaf of his book Borderlands: The Ultimate Exploration of the Unknown, Dr. Mike Dash “studied history at Cambridge University” and is “chief researcher at the Fortean Times, the journal of strange phenomena.” He describes the “Borderlands” of the title of his book as “an enigmatic world where almost anything seems possible.” Although a bizarre place, it is, as Dash describes it, also an inviting one. Consisting of “territories. . . where the known shades into [the] unknown, occurrences can be both terrifying and hilarious, and fiction mutates strangely into fact,” the Borderlands includes “grey areas, though the things that go on there are frequently intensely colorful.”

By their very nature, imaginary lands are intriguing. They’re places that many would like to visit, although, perhaps, they wouldn’t want to live there, which is why many writers, ancient, medieval, modern, and contemporary, have created imaginary places. Some are islands, others towns or cities. Quite a few are worlds, and some are worlds within worlds. There are so many imaginary locations, in fact, that a pair of enterprising writers, Alberto Manguel and Gianni Guadalupi, have written a sort of travel guide to them, The Dictionary of Imaginary Places.

Some of the more familiar imaginary places include:

- Mount Olympus (Greek mythology)

- Atlantis (Plato’s Timaeus)

- The nine worlds (Norse mythology)

- The five palaces of pleasure (one for each of the physical senses) in William Beckford’s The History of the Caliph Vathek

- Jules Verne’s Lincoln Island (The Mysterious Island)

- William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County

- L. Frank Baum’s Oz

- H. P. Lovecraft’s Dunwich, Innsmouth, and Kingsport

- C. S. Lewis’ Narnia

- J. R. R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth

- Stephen King’s trio of Maine towns, Castle Rock, Derry, and ‘Salem’s Lot.

There are plenty more!

One such place, which Europeans called “the New World,” really did--and does--exist, although it is not quite as new today as it was in 1492. If you live in North (or, for that matter, Central or South) America, you’re living in it, right now. Although it’s familiar enough today, it was once as strange and wonderful a place as any of which a writer, whether of fantasy, science fiction, horror, or otherwise, ever dreamed.

Dash’s Borderlands are not unknown, he says; in fact, “we have. . . been tracking them for centuries, but they remain” a mysterious landscape “to which existing guidebooks are often inadequate and sometimes dangerously misleading.” A “terra incognita,” its boundaries are fluid, rather than static, and tend to shift and change because of “answers” that “suggest questions,” scientific “anomalies,” revisionist history, and the “schismatics and heretics” or religion. Access to the Borderlands is easy, for its “ordinary doorways . . . stand permanently ajar,” although, travelers are warned, “at such a border crossing, reality and the unreal stand so close together we are not always aware we have moved from one world to another.”

Borderlands is not a physical landscape, but one of the mind, or, more specifically, of the imagination, although, at times, its fancies may be based, however loosely, upon facts. A glance at the book’s index shows the types of flora and fauna, the monuments and museums, and the other points of interest that this strange country offers to those who prefer to take the road less-often traveled. Those who have read the works of Charles Fort or the magazine launched in his memory and honor, The Fortean Times, will be familiar, already, with these sights: aliens, apparitions, Bigfoot, crop circles, demons, dinosaurs, the Flying Dutchman, ghosts, heaven, hell, ley lines, the Loch Ness monster, monsters, near-death experiences, psychic warfare, remote viewing, spontaneous human combustion, Stonehenge, theosophy, UFOs, vampires, Zener cards, and the like.

Dash’s first foray into Borderlands is “Strange Planet,” which, among other mysteries, recounts a fall of red snow in Antarctica. The phenomenon captures the attention of those who are interested in the odd, the curious, and the bizarre, and it is with the words “red snow” that the “Strange Planet” chapter begins.

The next paragraph solves the mystery of the red snow: “The Antarctic whiteness had been stained by penguin droppings, colored red by the shellfish that the birds had eaten.” This is an interesting explanation, but it’s also a bit disappointing. We expected something a little more out of the ordinary than penguins or, more specifically, their “droppings.” Such evidence is grotesque, perhaps, but it’s not especially horrible, even red.

But, wait! There’s more!

Dash explains that a rain in Italy delivered seeds from a tree that grows “only in central Africa and the Caribbean”; that sand, instead of water, rained upon “dusty Baghdad”; and that, in Stroud, Gloucestershire, “rose-colored frogs . . . tumbled from the sky, bouncing off umbrellas and pavements amid townspeople going about their business.” As a result of these anecdotes and others, Dash concludes that the planet earth is a much stranger place that anyone has imagined, even in accounts of strictly imaginary places: “This is a book about strange phenomena,” he alerts us in his second chapter, in case we had any doubts, its purpose to “argue that ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’ are inadequate categories when it comes to sifting strange phenomena.”

The rest of his book introduces readers to these “strange phenomena,” from the consideration of which Dash concludes three things: their experience “is utterly subjective,” “there seems to be no such thing as a consistently inexplicable phenomenon,” and “the human mind possesses an inherent sense of wonder” that enriches life and has “a powerful capacity to change lives.”

In “Sonnet: To Science,” Edgar Allan Poe observes that science has demystified the world, driving “the Hamadryad from the wood. . . . the Naiad from her flood,” “the Elfin from the green grass,” and “from me/ The summer dream beneath the tamarind tree.”

A visit to Borderlands such as Dash, and before him Fort, and others, charts for readers allows us to revisit the demon- and divinity-haunted woods of Poe’s sylvan countryside. However, Dash knows that we may be as reluctant to undertake the adventure as Frodo Baggins was to leave the comfort of his cozy Hobbit-hole in the familiar Shire, so, to excite our interest, he uses the metaphor of an exotic, new land on the edge of the known and the unknown, wherein “almost anything seems possible.”

The days of Chapman’s Homer and of John Keats, who waxed poetic concerning the translation, in which the latter poet wrote--

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

--are long gone, it seems.

It’s unfortunate that most people don’t want to undertake a journey simply for the journey’s sake, but, especially nowadays, and especially when the journey is figurative, requiring the reading of a book, such is often the case. Even Christopher Columbus needed more than the opportunity to go to new places and see new things to inspire him to hoist anchor and sail west. He needed to believe that he was undertaking a mission imposed upon him by God and that he would obtain costly spices, or even gold, enough to make his trip not only worth it to his sponsors, but to make himself a wealthy man as well--one, for whom, perhaps, his traveling days would then be forever over.

Dash, Mike. Borderlands: The Ultimate Exploration of the Unknown. Woodstock, NY: The Overlook Press, 2000.