Wednesday, January 7, 2009

Generating Horror Plots, Part V

Sunday, March 9, 2008

Borderlands: Realms of Gold? Okay, Maybe They’re Realms of Pyrite, But They Still Glitter Pretty Well

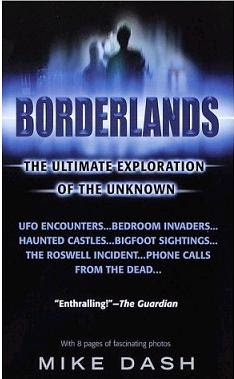

According to the flyleaf of his book Borderlands: The Ultimate Exploration of the Unknown, Dr. Mike Dash “studied history at Cambridge University” and is “chief researcher at the Fortean Times, the journal of strange phenomena.” He describes the “Borderlands” of the title of his book as “an enigmatic world where almost anything seems possible.” Although a bizarre place, it is, as Dash describes it, also an inviting one. Consisting of “territories. . . where the known shades into [the] unknown, occurrences can be both terrifying and hilarious, and fiction mutates strangely into fact,” the Borderlands includes “grey areas, though the things that go on there are frequently intensely colorful.”

By their very nature, imaginary lands are intriguing. They’re places that many would like to visit, although, perhaps, they wouldn’t want to live there, which is why many writers, ancient, medieval, modern, and contemporary, have created imaginary places. Some are islands, others towns or cities. Quite a few are worlds, and some are worlds within worlds. There are so many imaginary locations, in fact, that a pair of enterprising writers, Alberto Manguel and Gianni Guadalupi, have written a sort of travel guide to them, The Dictionary of Imaginary Places.

Some of the more familiar imaginary places include:

- Mount Olympus (Greek mythology)

- Atlantis (Plato’s Timaeus)

- The nine worlds (Norse mythology)

- The five palaces of pleasure (one for each of the physical senses) in William Beckford’s The History of the Caliph Vathek

- Jules Verne’s Lincoln Island (The Mysterious Island)

- William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County

- L. Frank Baum’s Oz

- H. P. Lovecraft’s Dunwich, Innsmouth, and Kingsport

- C. S. Lewis’ Narnia

- J. R. R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth

- Stephen King’s trio of Maine towns, Castle Rock, Derry, and ‘Salem’s Lot.

There are plenty more!

One such place, which Europeans called “the New World,” really did--and does--exist, although it is not quite as new today as it was in 1492. If you live in North (or, for that matter, Central or South) America, you’re living in it, right now. Although it’s familiar enough today, it was once as strange and wonderful a place as any of which a writer, whether of fantasy, science fiction, horror, or otherwise, ever dreamed.

Dash’s Borderlands are not unknown, he says; in fact, “we have. . . been tracking them for centuries, but they remain” a mysterious landscape “to which existing guidebooks are often inadequate and sometimes dangerously misleading.” A “terra incognita,” its boundaries are fluid, rather than static, and tend to shift and change because of “answers” that “suggest questions,” scientific “anomalies,” revisionist history, and the “schismatics and heretics” or religion. Access to the Borderlands is easy, for its “ordinary doorways . . . stand permanently ajar,” although, travelers are warned, “at such a border crossing, reality and the unreal stand so close together we are not always aware we have moved from one world to another.”

Borderlands is not a physical landscape, but one of the mind, or, more specifically, of the imagination, although, at times, its fancies may be based, however loosely, upon facts. A glance at the book’s index shows the types of flora and fauna, the monuments and museums, and the other points of interest that this strange country offers to those who prefer to take the road less-often traveled. Those who have read the works of Charles Fort or the magazine launched in his memory and honor, The Fortean Times, will be familiar, already, with these sights: aliens, apparitions, Bigfoot, crop circles, demons, dinosaurs, the Flying Dutchman, ghosts, heaven, hell, ley lines, the Loch Ness monster, monsters, near-death experiences, psychic warfare, remote viewing, spontaneous human combustion, Stonehenge, theosophy, UFOs, vampires, Zener cards, and the like.

Dash’s first foray into Borderlands is “Strange Planet,” which, among other mysteries, recounts a fall of red snow in Antarctica. The phenomenon captures the attention of those who are interested in the odd, the curious, and the bizarre, and it is with the words “red snow” that the “Strange Planet” chapter begins.

The next paragraph solves the mystery of the red snow: “The Antarctic whiteness had been stained by penguin droppings, colored red by the shellfish that the birds had eaten.” This is an interesting explanation, but it’s also a bit disappointing. We expected something a little more out of the ordinary than penguins or, more specifically, their “droppings.” Such evidence is grotesque, perhaps, but it’s not especially horrible, even red.

But, wait! There’s more!

Dash explains that a rain in Italy delivered seeds from a tree that grows “only in central Africa and the Caribbean”; that sand, instead of water, rained upon “dusty Baghdad”; and that, in Stroud, Gloucestershire, “rose-colored frogs . . . tumbled from the sky, bouncing off umbrellas and pavements amid townspeople going about their business.” As a result of these anecdotes and others, Dash concludes that the planet earth is a much stranger place that anyone has imagined, even in accounts of strictly imaginary places: “This is a book about strange phenomena,” he alerts us in his second chapter, in case we had any doubts, its purpose to “argue that ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’ are inadequate categories when it comes to sifting strange phenomena.”

The rest of his book introduces readers to these “strange phenomena,” from the consideration of which Dash concludes three things: their experience “is utterly subjective,” “there seems to be no such thing as a consistently inexplicable phenomenon,” and “the human mind possesses an inherent sense of wonder” that enriches life and has “a powerful capacity to change lives.”

In “Sonnet: To Science,” Edgar Allan Poe observes that science has demystified the world, driving “the Hamadryad from the wood. . . . the Naiad from her flood,” “the Elfin from the green grass,” and “from me/ The summer dream beneath the tamarind tree.”

A visit to Borderlands such as Dash, and before him Fort, and others, charts for readers allows us to revisit the demon- and divinity-haunted woods of Poe’s sylvan countryside. However, Dash knows that we may be as reluctant to undertake the adventure as Frodo Baggins was to leave the comfort of his cozy Hobbit-hole in the familiar Shire, so, to excite our interest, he uses the metaphor of an exotic, new land on the edge of the known and the unknown, wherein “almost anything seems possible.”

The days of Chapman’s Homer and of John Keats, who waxed poetic concerning the translation, in which the latter poet wrote--

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

--are long gone, it seems.

It’s unfortunate that most people don’t want to undertake a journey simply for the journey’s sake, but, especially nowadays, and especially when the journey is figurative, requiring the reading of a book, such is often the case. Even Christopher Columbus needed more than the opportunity to go to new places and see new things to inspire him to hoist anchor and sail west. He needed to believe that he was undertaking a mission imposed upon him by God and that he would obtain costly spices, or even gold, enough to make his trip not only worth it to his sponsors, but to make himself a wealthy man as well--one, for whom, perhaps, his traveling days would then be forever over.

Dash, Mike. Borderlands: The Ultimate Exploration of the Unknown. Woodstock, NY: The Overlook Press, 2000.

Wednesday, February 13, 2008

Everyday Horrors: Anglerfish

What lies beneath? Three-fifths of the earth’s surface is covered with water, and the oceans are deep. Strange, shadowy shapes weave and waver beneath the waves, suggesting fabulous creatures beyond human ken. As well as warnings of boiling seas, the maps of ancient and medieval mariners were crowded with images of mythical sea monsters that sailors swore they’d seen. These strange, misshapen creatures, sometimes of colossal size, greater even than that of the sailing ships from which, allegedly, they were seen, are revealing, if not of nature per se, of human nature, at least, and of the nature of fantasy.

Usually, scientists believe, such creatures have some real-world inspiration, but they are products of fear more than of observation, a part of something mysterious giving rise to something even more baffling and horrible. Exaggeration is often at work, too, in the creation of the serpents of the sea. Attributes are multiplied, enlarged, combined, or, in a few cases, denied. Jules Verne combined a parrot’s beak with an octopus to create the giant squid of which he writes in 20,000 Leagues Beneath the Sea, and the delta of a river may have given birth to the many-headed Grecian hydra that Hercules and Iolaus slew. Columbus, as we saw in a previous post, may have mistaken manatees for mermaids.

As an American Museum of Natural History piece points out, monsters are also born of misinterpretations, with seaweed being taken for sea serpents and a “deformed blacksnake” having been thought to be a newborn specimen. Moreover, stories told one place are retold in another region, and, often in the retelling, the monsters at their hearts are reformulated and recast, becoming different, at least, if not more hideous and menacing. Before long, there is such a disparity between the original monster and its offspring that any family resemblance is lost, and the two relatives are mistaken for entirely distinct creatures. Sometimes, such monsters are even “manufactured,” purposely, as hoaxes, as the article observes, citing none other than P. T. Barnum as a perpetuator of such a fraud. The showman’s version consisted of a monkey’s head, a fish’s tail, and, perhaps, fish bones and papier-mâché.

However, the world’s oceans, especially at their lowest depths, offers many a strange creature that, with a little modification, might well suggest possibilities for horror story monsters. We’re going to mention only one in this post--the anglerfish, which is known for its method of obtaining prey and its way of reproducing others of its kind.

A moveable fishing rod of sorts grows from their foreheads. It is baited, so to speak, at its tip with an blob of flesh that attracts would-be carnivores of the deep. The anglerfish can wiggle its fleshly fishing rod, called an illicium, in all directions to lure prey close enough to its jaws for the anglerfish to swallow them in a single gulp. The jaws spring into action automatically, by reflex, when the prey brushes its illicium. Some anglerfish are luminescent. Both jaws and stomach can expand so that the anglerfish can swallow prey twice its own size.

Some anglerfish have modified pectoral fins that allow them to “walk” upon the ocean floor, where it conceals itself in the sand or among seaweed. It can change the color of its body to camouflage itself.

Their method of mating is as peculiar as any of the anglerfish’s other characteristic behaviors. When the male reaches maturity, its digestive system degenerates to the point that it is no longer able to feed itself, and it attaches itself to the much larger female’s head, biting into her flesh. The male’s body then releases an enzyme that digests its mouth and the flesh of the female at the site at which the male has attached itself to her, fusing the two sexes so that the female and what is left of the male--eventually nothing but its gonads, or sex organs--share the same blood supply.

There are as many as eighteen families of anglerfish, including humpbacks, monkfish, frogfish, seadevils, footballfish, sea toads, and batfish. Those who have sampled them compare their taste to that of lobster tails.

“Everyday Horrors: Anglerfish” is the part of a series of “everyday horrors” that will be featured in Chillers and Thrillers: The Fiction of Fear. These “everyday horrors” continue, in many cases, to appear in horror fiction, literary, cinematographic, and otherwise.

Paranormal vs. Supernatural: What’s the Diff?

Sometimes, in demonstrating how to brainstorm about an essay topic, selecting horror movies, I ask students to name the titles of as many such movies as spring to mind (seldom a difficult feat for them, as the genre remains quite popular among young adults). Then, I ask them to identify the monster, or threat--the antagonist, to use the proper terminology--that appears in each of the films they have named. Again, this is usually a quick and easy task. Finally, I ask them to group the films’ adversaries into one of three possible categories: natural, paranormal, or supernatural. This is where the fun begins.

It’s a simple enough matter, usually, to identify the threats which fall under the “natural” label, especially after I supply my students with the scientific definition of “nature”: everything that exists as either matter or energy (which are, of course, the same thing, in different forms--in other words, the universe itself. The supernatural is anything which falls outside, or is beyond, the universe: God, angels, demons, and the like, if they exist. Mad scientists, mutant cannibals (and just plain cannibals), serial killers, and such are examples of natural threats. So far, so simple.

What about borderline creatures, though? Are vampires, werewolves, and zombies, for example, natural or supernatural? And what about Freddy Krueger? In fact, what does the word “paranormal” mean, anyway? If the universe is nature and anything outside or beyond the universe is supernatural, where does the paranormal fit into the scheme of things?

According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word “paranormal,” formed of the prefix “para,” meaning alongside, and “normal,” meaning “conforming to common standards, usual,” was coined in 1920. The American Heritage Dictionary defines “paranormal” to mean “beyond the range of normal experience or scientific explanation.” In other words, the paranormal is not supernatural--it is not outside or beyond the universe; it is natural, but, at the present, at least, inexplicable, which is to say that science cannot yet explain its nature. The same dictionary offers, as examples of paranormal phenomena, telepathy and “a medium’s paranormal powers.”

Wikipedia offers a few other examples of such phenomena or of paranormal sciences, including the percentages of the American population which, according to a Gallup poll, believes in each phenomenon, shown here in parentheses: psychic or spiritual healing (54), extrasensory perception (ESP) (50), ghosts (42), demons (41), extraterrestrials (33), clairvoyance and prophecy (32), communication with the dead (28), astrology (28), witchcraft (26), reincarnation (25), and channeling (15); 36 percent believe in telepathy.

As can be seen from this list, which includes demons, ghosts, and witches along with psychics and extraterrestrials, there is a confusion as to which phenomena and which individuals belong to the paranormal and which belong to the supernatural categories. This confusion, I believe, results from the scientism of our age, which makes it fashionable for people who fancy themselves intelligent and educated to dismiss whatever cannot be explained scientifically or, if such phenomena cannot be entirely rejected, to classify them as as-yet inexplicable natural phenomena. That way, the existence of a supernatural realm need not be admitted or even entertained. Scientists tend to be materialists, believing that the real consists only of the twofold unity of matter and energy, not dualists who believe that there is both the material (matter and energy) and the spiritual, or supernatural. If so, everything that was once regarded as having been supernatural will be regarded (if it cannot be dismissed) as paranormal and, maybe, if and when it is explained by science, as natural. Indeed, Sigmund Freud sought to explain even God as but a natural--and in Freud’s opinion, an obsolete--phenomenon.

Meanwhile, among skeptics, there is an ongoing campaign to eliminate the paranormal by explaining them as products of ignorance, misunderstanding, or deceit. Ridicule is also a tactic that skeptics sometimes employ in this campaign. For example, The Skeptics’ Dictionary contends that the perception of some “events” as being of a paranormal nature may be attributed to “ignorance or magical thinking.” The dictionary is equally suspicious of each individual phenomenon or “paranormal science” as well. Concerning psychics’ alleged ability to discern future events, for example, The Skeptic’s Dictionary quotes Jay Leno (“How come you never see a headline like 'Psychic Wins Lottery'?”), following with a number of similar observations:

Psychics don't rely on psychics to warn them of impending disasters. Psychics don't predict their own deaths or diseases. They go to the dentist like the rest of us. They're as surprised and disturbed as the rest of us when they have to call a plumber or an electrician to fix some defect at home. Their planes are delayed without their being able to anticipate the delays. If they want to know something about Abraham Lincoln, they go to the library; they don't try to talk to Abe's spirit. In short, psychics live by the known laws of nature except when they are playing the psychic game with people.In An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural, James Randi, a magician who exercises a skeptical attitude toward all things alleged to be paranormal or supernatural, takes issue with the notion of such phenomena as well, often employing the same arguments and rhetorical strategies as The Skeptic’s Dictionary.

In short, the difference between the paranormal and the supernatural lies in whether one is a materialist, believing in only the existence of matter and energy, or a dualist, believing in the existence of both matter and energy and spirit. If one maintains a belief in the reality of the spiritual, he or she will classify such entities as angels, demons, ghosts, gods, vampires, and other threats of a spiritual nature as supernatural, rather than paranormal, phenomena. He or she may also include witches (because, although they are human, they are empowered by the devil, who is himself a supernatural entity) and other natural threats that are energized, so to speak, by a power that transcends nature and is, as such, outside or beyond the universe. Otherwise, one is likely to reject the supernatural as a category altogether, identifying every inexplicable phenomenon as paranormal, whether it is dark matter or a teenage werewolf. Indeed, some scientists dedicate at least part of their time to debunking allegedly paranormal phenomena, explaining what natural conditions or processes may explain them, as the author of The Serpent and the Rainbow explains the creation of zombies by voodoo priests.

Based upon my recent reading of Tzvetan Todorov's The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to the Fantastic, I add the following addendum to this essay.

According to Todorov:

The fantastic. . . lasts only as long as a certain hesitation [in deciding] whether or not what they [the reader and the protagonist] perceive derives from "reality" as it exists in the common opinion. . . . If he [the reader] decides that the laws of reality remain intact and permit an explanation of the phenomena described, we can say that the work belongs to the another genre [than the fantastic]: the uncanny. If, on the contrary, he decides that new laws of nature must be entertained to account for the phenomena, we enter the genre of the marvelous (The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre, 41).Todorov further differentiates these two categories by characterizing the uncanny as “the supernatural explained” and the marvelous as “the supernatural accepted” (41-42).

Interestingly, the prejudice against even the possibility of the supernatural’s existence which is implicit in the designation of natural versus paranormal phenomena, which excludes any consideration of the supernatural, suggests that there are no marvelous phenomena; instead, there can be only the uncanny. Consequently, for those who subscribe to this view, the fantastic itself no longer exists in this scheme, for the fantastic depends, as Todorov points out, upon the tension of indecision concerning to which category an incident belongs, the natural or the supernatural. The paranormal is understood, by those who posit it, in lieu of the supernatural, as the natural as yet unexplained.

And now, back to a fate worse than death: grading students’ papers.

My Cup of Blood

Anyway, this is what I happen to like in horror fiction:

Small-town settings in which I get to know the townspeople, both the good, the bad, and the ugly. For this reason alone, I’m a sucker for most of Stephen King’s novels. Most of them, from 'Salem's Lot to Under the Dome, are set in small towns that are peopled by the good, the bad, and the ugly. Part of the appeal here, granted, is the sense of community that such settings entail.

Isolated settings, such as caves, desert wastelands, islands, mountaintops, space, swamps, where characters are cut off from civilization and culture and must survive and thrive or die on their own, without assistance, by their wits and other personal resources. Many are the examples of such novels and screenplays, but Alien, The Shining, The Descent, Desperation, and The Island of Dr. Moreau, are some of the ones that come readily to mind.

Total institutions as settings. Camps, hospitals, military installations, nursing homes, prisons, resorts, spaceships, and other worlds unto themselves are examples of such settings, and Sleepaway Camp, Coma, The Green Mile, and Aliens are some of the novels or films that take place in such settings.

Anecdotal scenes--in other words, short scenes that showcase a character--usually, an unusual, even eccentric, character. Both Dean Koontz and the dynamic duo, Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, excel at this, so I keep reading their series (although Koontz’s canine companions frequently--indeed, almost always--annoy, as does his relentless optimism).

Atmosphere, mood, and tone. Here, King is king, but so is Bentley Little. In the use of description to terrorize and horrify, both are masters of the craft.

Innovation. Bram Stoker demonstrates it, especially in his short story “Dracula’s Guest,” as does H. P. Lovecraft, Edgar Allan Poe, Shirley Jackson, and a host of other, mostly classical, horror novelists and short story writers. For an example, check out my post on Stoker’s story, which is a real stoker, to be sure. Stephen King shows innovation, too, in ‘Salem’s Lot, The Shining, It, and other novels. One might even argue that Dean Koontz’s something-for-everyone, cross-genre writing is innovative; he seems to have been one of the first, if not the first, to pen such tales.

Technique. Check out Frank Peretti’s use of maps and his allusions to the senses in Monster; my post on this very topic is worth a look, if I do say so myself, which, of course, I do. Opening chapters that accomplish a multitude of narrative purposes (not usually all at once, but successively) are attractive, too, and Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child are as good as anyone, and better than many, at this art.

A connective universe--a mythos, if you will, such as both H. P. Lovecraft and Stephen King, and, to a lesser extent, Dean Koontz, Bentley Little, and even Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child have created through the use of recurring settings, characters, themes, and other elements of fiction.

A lack of pretentiousness. Dean Koontz has it, as do Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, Bentley Little, and (to some extent, although he has become condescending and self-indulgent of late, Stephen King); unfortunately, both Dan Simmons and Robert McCammon have become too self-important in their later works, Simmons almost to the point of becoming unreadable. Come on, people, you’re writing about monsters--you should be humble.

Longevity. Writers who have been around for a while usually get better, Stephen King, Dan Simmons, and Robert McCammon excepted.