Audiences who watched An American Werewolf in London, The Howling, or even earlier werewolf movies were treated (if such a word may be rightly used in such a context) to the sights (and sounds) of men and women being transformed into wolves--or, rather, bipedal werewolves. The shapes of their skulls changed radically, noses elongating into snouts; mouths enlarging into gaping maws full of sharp, jagged teeth; and ears popping up from their heads. The pupils in their eyes became vertical slits inside yellow irises. Their bodies bulked up like those of athletes on steroids, hands and feet stretching into long paws, tails sprouting from their backs, and fur covering every square inch of their bodies. It wasn’t a pretty sight. In fact, it was pretty appalling.

Other, equally horrific transformations have also been captured on celluloid. In The Fly, a scientist inventing a teleportation device that disassembles one’s molecules at Point A to reassemble them, at light speed, at Point B, is transformed into a fly when one of these insects’ DNA is accidentally mixed with the scientist’s own genetic material, just as the teleportation process gets underway. In The Invasion of the Body Snatchers, alien pods replicate people, producing doppelgangers left and right, which is bad enough in itself--who needs two Paris Hiltons or Lindsay Lohans?--but it’s even worse when a man and his dog are merged during one such transformation, resulting in a truly bizarre creature consisting of a dog’s body with his master’s head--and face.

Even before horror (and science fiction), there were such transformations, of course. Quite a few of them took place in ancient myths. Ovid wrote of many in his poem, Metamorphoses, in which a statue becomes a woman, girls pursued by would-be rapists are turned into trees, and people are changed into such animals as magpies, deer, a bear, a wolf, and spiders. Even in the Bible, a few such metamorphoses occur, as when God turns Lot’s wife into a pillar of salt or Moses (and pharaoh’s magicians) transform sticks into serpents.

In reality, metamorphoses also occur. Women, becoming pregnant, for example, change shape rather drastically over a relatively short period of time. Living bodies become corpses. Men sometimes develop womanly breasts (a condition known as gynecomastia) and may even lactate, whereas a few women grow mustaches, beards, and thicker-than-usual body hair. Before science could explain such apparently miraculous occurrences, myth-makers made up myths to account for such extraordinary, unusual, or extreme transformations. Today, writers in such genres as fantasy, horror, and science fiction continue to do so, creating monstrosities that, one may suppose, would warm the hearts of editors and publishers at DC and Marvel Comics.

Before science, the world was full of divinities and demons, and, often, it was the activity of such spirits that caused the wonders of the world, including the metamorphoses through which rocks, plants, animals, and people sometimes went. In “

The Growth of Explanatory Transformation Myth,” Professor Andrew Dickson White lists several of the many ways in which myth was used to explain--or to explain away--the oddities and seeming wonders of the world, such as “mountains, rocks, and boulders seemingly misplaced.” Many of these were the missiles, he says, of warring gods. In the Middle East, Christian or Muslim religion explains the odd appearance or unlikely locations of these natural objects, just as, in Asia, Buddhism accounts for the strange rock formations and “in Teutonic lands, as a rule, wherever a strange rock or stone is found, there will be found a myth or a legend, heathen or Christian, to account for it.”

Of course, more than just the appearance and location of rocks and mountains--or of even the lay of the land in general--is explained by etiological (explanatory) myths, and the explanations deal with the “why” as well as the “how” of things, answering such fundamental questions as why people die, why people have skins of various colors, why animals have certain features, why this ruler rules, or why this rite is practiced.

The College of Siskiyous (yes, it

does exist; it’s a community college in Weed, California (yes, it

does sound like a joke), near Mt. Shasta) offers a (a rather oddly written) summary of the role of the

etiological myth, differentiating it, at the same time, from science’s similar role in explaining the whys and wherefores of the world:

While science might [?] say the sky is blue due to excited nitrogen and refractive dust particles, myth is more likely to explain [that] the blue is due to a giant bird’s blue feathers or the cold breath of an ancient god.

The same site challenges visitors to create their own etiological myth, offering several examples and these useful guidelines:

Your etiological narrative can be either a myth or a folktale. It can recount the creation of a well-known geographical feature (Mt Shasta, Lake Tahoe), specific animal traits (why dogs bark, why ants work together), taboos (why incest is wrong), customs (why people are buried underground). Please be descriptive. You may use dialogue, figurative language, or any other rhetorical device you wish. Try to imagine you are a member of an ancient culture, a pre-scientific culture, and myth is your vehicle of explanation. Indicate in the title whether your narrative is an etiological myth or an etiological folktale.

Writers of fantasy, science fiction, and horror may want to employ a similar strategy in creating fantasy worlds, scientific marvels, or monsters. Forget the scientific explanation as to how and why something is what it is or does what it does. Instead, recapture the spirit, so to speak, of our ancient ancestors, looking at the world anew, or see it as young children see it, fresh and vivid. Ask yourself, How? Ask yourself, Why? (a child’s favorite question, as every parent knows). Be creative. As a result, you’re apt to infuse your fiction with excitement, glamour, chills, and thrills.

At

Chillers and Thrillers, we don’t denigrate science. In fact, we appreciate and admire it. Besides, since many horror stories involve mad scientists and their attempts to transform, if not dominate, the world, we find the principles and theories of the sciences to be very useful. Nevertheless, from a mystical point of view, such as was common among pre-scientific societies, science seems to have demystified the world, depleting it of its deities and its demons, as Edgar Allan Poe observes in his “Sonnet--To Science” (written when he was but a lad of twenty years):

Science! true daughter of Old Time thou art!

Who alterest all things with thy peering eyes.

Why preyest thou thus upon the poet's heart,

Vulture, whose wings are dull realities?

How should he love thee? or how deem thee wise?

Who wouldst not leave him in his wandering

To seek for treasure in the jewelled skies,

Albeit he soared with an undaunted wing?

Hast thou not dragged Diana from her car?

And driven the Hamadryad from the wood

To seek a shelter in some happier star?

Hast thou not torn the Naiad from her flood,

The Elfin from the green grass, and from me

The summer dream beneath the tamarind tree?

In “Intimations of Immortality,” William Wordsworth laments a similar loss of the magic and mystery of nature, as it appears through the eyes of a child, capturing, at the same time, a sense of the very “glory” the passing of which he mourns:

There was a time when meadow, grove, and stream,

The earth, and every common sight,

To me did seem

Apparell'd in celestial light,

The glory and the freshness of a dream.

It is not now as it hath been of yore;--

Turn wheresoe'er I may,

By night or day,

The things which I have seen I now can see no more.

The rainbow comes and goes,

And lovely is the rose;

The moon doth with delight

Look round her when the heavens are bare;

Waters on a starry night

Are beautiful and fair;

The sunshine is a glorious birth;

But yet I know, where'er I go,

That there hath pass'd away a glory from the earth. . . .

As long as we persist in seeing a snake only as science defines it--as “a legless reptile of the sub-order Serpentes with a long, thin body and a fork-shaped tongue,” (Allwords.com)--rather than as Emily Dickinson’s “narrow fellow in the grass” or D. H. Lawrence’s “king,” it shall never appear to us with the vividness--or the sheer presence--as Dickinson’s serpent:

A narrow fellow in the grass

Occasionally rides;

You may have met him,--did you not,

His notice sudden is.

The grass divides as with a comb,

A spotted shaft is seen;

And then it closes at your feet

And opens further on.

He likes a boggy acre,

A floor too cool for corn.

Yet when a child, and barefoot,

I more than once, at morn,

Have passed, I thought, a whip-lash

Unbraiding in the sun,--

When, stooping to secure it,

It wrinkled, and was gone.

Several of nature's people

I know, and they know me;

I feel for them a transport

Of cordiality;

But never met this fellow,

Attended or alone,

Without a tighter breathing,

And zero at the bone.

Nor shall we see this “legless reptile” as Lawrence saw it:

A snake came to my water-trough

On a hot, hot day, and I in pyjamas for the heat,

To drink there.

In the deep, strange-scented shade of the great dark carob-tree

I came down the steps with my pitcher

And must wait, must stand and wait, for there he was at the trough before me.

He reached down from a fissure in the earth-wall in the gloom

And trailed his yellow-brown slackness soft-bellied down, over the edge of the stone trough

And rested his throat upon the stone bottom,

And where the water had dripped from the tap, in a small clearness,

He sipped with his straight mouth,

Softly drank through his straight gums, into his slack long body,

Silently.

Someone was before me at my water-trough,

And I, like a second comer, waiting.

He lifted his head from his drinking, as cattle do,

And looked at me vaguely, as drinking cattle do,

And flickered his two-forked tongue from his lips, and mused a moment,

And stooped and drank a little more,

Being earth-brown, earth-golden from the burning bowels of the earth

On the day of Sicilian July, with Etna smoking.

The voice of my education said to me

He must be killed,

For in Sicily the black, black snakes are innocent, the gold are venomous.

And voices in me said, If you were a man

You would take a stick and break him now, and finish him off.

But must I confess how I liked him,

How glad I was he had come like a guest in quiet, to drink at my water-trough

And depart peaceful, pacified, and thankless,

Into the burning bowels of this earth?

Was it cowardice, that I dared not kill him?

Was it perversity, that I longed to talk to him?

Was it humility, to feel so honoured?

I felt so honoured.

And yet those voices:

If you were not afraid, you would kill him!

And truly I was afraid, I was most afraid,

But even so, honoured still more

That he should seek my hospitality

From out the dark door of the secret earth.

He drank enough

And lifted his head, dreamily, as one who has drunken,

And flickered his tongue like a forked night on the air, so black,

Seeming to lick his lips,

And looked around like a god, unseeing, into the air,

And slowly turned his head,

And slowly, very slowly, as if thrice adream,

Proceeded to draw his slow length curving round

And climb again the broken bank of my wall-face.

And as he put his head into that dreadful hole,

And as he slowly drew up, snake-easing his shoulders, and entered farther,

A sort of horror, a sort of protest against his withdrawing into that horrid black hole,

Deliberately going into the blackness, and slowly drawing himself after,

Overcame me now his back was turned.

I looked round, I put down my pitcher,

I picked up a clumsy log

And threw it at the water-trough with a clatter.

I think it did not hit him,

But suddenly that part of him that was left behind convulsed in undignified haste.

Writhed like lightning, and was gone

Into the black hole, the earth-lipped fissure in the wall-front,

At which, in the intense still noon, I stared with fascination.

And immediately I regretted it.

I thought how paltry, how vulgar, what a mean act!

I despised myself and the voices of my accursed human education.

And I thought of the albatross

And I wished he would come back, my snake.

For he seemed to me again like a king,

Like a king in exile, uncrowned in the underworld,

Now due to be crowned again.

And so, I missed my chance with one of the lords

Of life.

And I have something to expiate:

A pettiness.

All good fiction, whatever its genre, immerses its readers in the world, in sensory perceptions, in experience, bringing to life again that which was dead, and presenting to the attention that which is taken for granted, forgotten, or ignored. Intensity of presence, like the quality of mystery, is a hallmark of superior writing, especially in regard to imaginative prose or poetry.

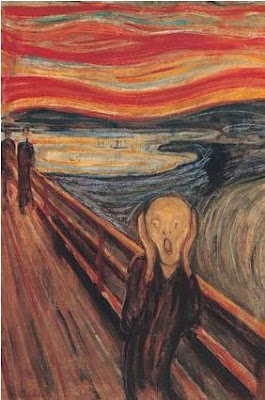

However, as we have said before, horror is horror, not romance (or, for that matter, fantasy or science fiction or any other genre, although horror fiction may contain elements of any of these, and other, types of literature). Horror fiction has its own bent, its own interest, its own passionate concern. For horror, this focus is the dreadful, the horrific, the appalling. Horror fiction is, first and foremost, after all, the fiction of fear. It is fear that is the “certain slant of light” with which horror fiction is concerned, to borrow a phrase from another of Dickinson’s poems, one that has a peculiar suitability to chillers and thrillers:

There's a certain Slant of light,

Winter Afternoons--

That oppresses, like the Heft

Of Cathedral Tunes--

Heavenly Hurt, it gives us--

We can find no scar,

But internal difference,

Where the meanings are--

None may teach it--Any--

'Tis the Seal Despair--

An imperial affliction Sent us of the Air--

When it comes, the Landscape listens--

Shadows--hold their breath--

When it goes, 'tis like the Distance

On the look of Death--

We discuss this “Heavenly Hurt” to which Dickinson alludes in a more detailed, if less poetic, fashion in “

Chillers and Thrillers: The Fiction of Fear,” our blog’s inaugural post:

Horror fiction provides us with a way of exercising and of exorcising our inner demons, but it also reminds us that life is short, and it suggests to us that we should be grateful to be alive, that we should appreciate what we have, and that we should take nothing for granted--not life, limb, mind, health, loved ones, or anything else. Horror fiction is a literary memento mori, or reminder of death.

In the shadow of death, we appreciate and enjoy the fullness of life.No one ever wrote a horror story about a man who stubbed his toe or a woman who broke a nail. Horror fiction's themes are bigger; they're more important. They're as vast and profound as the most critically important and most highly valued of all things. Horror fiction, by threatening us with the loss of that which is really important, shows us what truly matters. As such, it's a guide, implicitly, to the good life.Horror fiction also shows us, sometimes, at least, that no matter how bad things are, we can survive our losses. We can regroup, individually or collectively, subjectively or objectively, and we can continue to fight the good fight.

It is this “slant of light” of which Dickinson writes, or something very much like it, to which H. P. Lovecraft refers in “

Notes on Writing Weird Fiction”:

My reason for writing stories is to give myself the satisfaction of visualising more clearly and detailedly and stably the vague, elusive, fragmentary impressions of wonder, beauty, and adventurous expectancy which are conveyed to me by certain sights (scenic, architectural, atmospheric, etc.), ideas, occurrences, and images encountered in art and literature. I choose weird tories because they suit my inclination best--one of my strongest and most persistent wishes being to achieve, momentarily, the illusion of some strange suspension or violation of the galling limitations of time, space, and natural law which forever imprison us and frustrate our curiosity about the infinite cosmic spaces beyond the radius of our sight and analysis. These stories frequently emphasise the element of horror because fear is our deepest and strongest emotion, and the one which best lends itself to the creation of Nature-defying illusions. Horror and the unknown or the strange are always closely connected, so that it is hard to create a convincing picture of shattered natural law or cosmic alienage or "outsideness" without laying stress on the emotion of fear. The reason why time plays a great part in so many of my tales is that this element looms up in my mind as the most profoundly dramatic and grimly terrible thing in the universe. Conflict with time seems to me the most potent and fruitful theme in all human expression.

In setting aside the explanations of science and delving, once more, into that deep reservoir of what science might characterize as superstition, but what others might call faith, and seeing the world anew, as our ancient ancestors did or as young children still do, we reconnect with the mystery (and the dread, or awe) of life, immersing ourselves in the experience of Rudolph Otto’s numinous, the “mysterium tremendum et fascinans” that inspires faith in powers “wholly other” than, and greater than, our own, some of which may be friendly and helpful and some of which may be fiends and monsters. The numinous is neither exclusively divine nor exclusively demonic; rather, it is a quality of the mind or of an experience, which, in the Bible (and in the work of Soren Kierkegaard), is sometimes described as one of “fear and trembling.” In The Idea of the Holy, Otto describes the numinous, in part, as:

The feeling of it may at times come sweeping like a gentle tide, pervading the mind with a tranquil mood of deepest worship. It may pass over into a more set and lasting attitude of the soul, continuing, as it were, thrillingly vibrant and resonant, until at last it dies away and the soul resumes its "profane," non-religious mood of everyday experience. It may burst in sudden eruption up from the depths of the soul with spasms and convulsions, or lead to the strongest excitments, to intoxicated frenzy, to transport, and to ecstasy. It has its wild and demonic forms and can sink to an almost grisly horror and shuddering (12-13).

As Otto defines the term, the numinous is awful (that is, it fills one with awe), overpowering, urgent, fascinating, and completely alien to human experience.

In our “

Why Monsters? Why Metaphors?” post, we identified the use of the monstrous, or grotesque, as having a purpose similar to that which Walker Percy and Flannery O’Connor, each in his or her own way, seeks to accomplish in his or her respective fiction; it seeks to grasp, to seize, and to awaken one to the presence of the depth and mystery of existence. We might also characterize this purpose as being to recover a perception of the holy, or the numinous. We said that monsters are often used as metaphors in horror fiction because monsters “they have presence”:

What do I mean by “presence”? Walker Percy illustrates the idea well in his novel The Moviegoer. His protagonist, Binx Bolling, a soldier at this time in the story, has been injured in a battle. As he lies upon the battlefield, he catches sight of a dung beetle. Normally, he probably wouldn’t have seen the insect and, if he had, he wouldn’t have been likely to devote careful study to it. However, he is not operating under normal circumstances, and he is astonished to see the beetle, in all its glorious detail. It has presence for him; it has become visible. In doing so, it has shed the malaise of everydayness and become real. Here’s the way that Percy describes the scene:

. . . I remembered the first time the search occurred to me. I came to myself under a chindolea bush. . . . Six inches from my nose a dung beetle was scratching around under the leaves. As I watched there awoke within me an immense curiosity. I was onto something.

Later, a similar experience happens to Binx:

. . . This morning, as I got up, I dressed as usual and began as usual to put my belongings into my pockets: wallet, notebook. . . pencil, keys, handkerchief, slide rule. . . . They looked both unfamiliar and at the same time full of clues. . . . What was unfamiliar about them was that I could see them. They might have belonged to someone else. A man can look at this little pile on his bureau for thirty years and never once see it. It is as invisible as his own hand. Once I saw it, however, the search became possible. . . .

We can all remember the times, usually as a child, during which we could lose ourselves in the contemplation of everyday objects such as a daisy or a drop of dew. We could see each grain of pollen, every glistening color of the rainbow that seemed to emanate from within the clear drop of early morning dew as it shimmered upon a green leaf. All the world was present in a grain of sand.Then, as we grew older, things changed--or we changed. Saddled with responsibilities and governed by social expectations and conventions, our priorities changed. Eventually, we changed. We no longer had time to appreciate, admire, and embrace the world around us. We became alienated from our environment and estranged from or surroundings. We took for granted the wonders and enchantments of nature. More and more, the world began to disappear as we took birds and brooks, sun and moon, mountains and beaches, and pine trees and breezes for granted. The malaise of everydayness spread until we were nearly blind and deaf to the world around us. Things and people alike began to lack presence. Occasionally, something happens, and we see again. We hear again. The world becomes present to us again, as the dung beetle became present for Binx. We recover the world or, perhaps, only a tiny portion of the world--maybe nothing more than a dung beetle. But it’s a start. If we can see an insect today, maybe someday we can see a forest or, looking into a looking-glass, even ourselves. Monsters make us sit up and take notice. They grab our attention. They have immediate and intense presence, even in a world devoid of detail and force. Like a snake, a monster’s hard to miss. Emily Dickinson suggests this quality when she describes a hiker crossing a serpent’s path. . . . The monster, likewise, is noticeable, immediately. That’s one reason that horror writers employ the monstrous. Monsters have presence. They’re bold font, italics, exclamation points, underlining.

Flannery O’Connor, asked why her fiction contains so many grotesque characters--physically, emotionally, or spiritually deformed characters (monsters, of a sort, really)--implied that she wrote for a “hostile audience“ and explained that, “to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost blind you draw large, startling figures.”

In “

Creating Mood in Horror Fiction,”our review of Bram Stoker’s short story, “Dracula’s Guest,” we showed how a great writer in the horror genre creates a sense of the numinous by the way that he describes the various incidents which occur in the narrative and his protagonist’s experiences and perceptions. The techniques that Stoker uses to accomplish this feat are many and varied, as we point out in our review, but we want to recall a couple that seem especially relevant to our present discussion:

. . . The coachman’s account of the abandoned village gives the Englishman a definite destination, and he undertakes a hike into the valley, in search of the site of the deserted town. From a distance, the valley seemed enchanting, pleasant, and inviting, but, as he enters the basin, its appearance changes--or seems to change--becoming “desolation itself.” He pauses to rest, and the cold winter’s night and the gathering of high storm clouds cause him to realize that a blizzard is approaching. As he resumes his trek, the countryside appears “more picturesque,” and he becomes lost to time as he enjoys the “charm of [its] beauty” until, at length, “deepening twilight” turns his thoughts to finding his way back “home.” Stoker adds a discordant note to the “picaresque” scene, as, again, the Englishman hears the sound of a wolf. In this description of the woods, as in others to come, Stoker masterfully suggests that there may be some unseen power, acting behind the scenes, to manipulate and control the protagonist’s perceptions, thoughts, and feelings. Readers are apt to get a strong impression that the valley, including its woods, is truly enchanted--that is, magical--and that the environment has cast a spell upon the traveler, seeming now desolate, now charming, and making him forget both himself and the time of day as he hikes farther and farther on his way to his “unholy” destination, Walpurgis Night fast approaching.

Earlier in the story, the coachman predicted the advent of a snowstorm, and the gathering clouds support Johann’s forecast. Now, when a blizzard begins, the storm seems natural enough. Indeed, it is expected. At the same time, however, because of the way that Stoker has described the woodland valley, readers are apt to wonder whether the occult power that seems to control the landscape may also be controlling the weather, for the blizzard begins at a most convenient moment, just as the traveler glimpses, through the trees, what appears to be a building and thinks that he has likely discovered the long-abandoned village that has become the object of his quest. This possibility is strengthened by the chorus of wolves’ howls he hears at this same moment and by the way in which the cypress trees form an “alley” that leads to the site. The storm, the wolves, and the “alley” of cypresses all seem to conspire, as it were, to guide and direct the Englishman to the same location. The sense that nature itself is being manipulated and controlled by an unseen power is strong, as is the sense that this same power (or another) is secretly observing the Englishman. These techniques increase the story’s suspense by multiplying the power of the narrative’s unseen protagonist, for whoever or whatever can control nature must be not only supernatural but also extremely powerful. The fact that the adversary is unseen is unnerving as well, because, obviously, one cannot defend oneself against an enemy that he or she cannot see. The invisibility of the adversary also lends it a certain majesty, suggesting, again, that it is beyond human ken. However, Stoker also leaves open the narrow possibility--and the possibility seems to become narrower all the time--that perhaps all is normal, except for the Englishman himself. Perhaps the protagonist merely believes that these incidents have a greater significance than they actually have. So far, there has been no definitive reason to suspect that the apparently supernatural force operating behind the scenes is supernatural or, in fact, that it exists at all. . . .

By using similar techniques, we argued, in “

Horror By the Slice,” our review of “The Lurking Fear,” Lovecraft also succeeds in creating the impression of a mysterious, unseen power operating, as it were, behind the scenes, or, in other words, he likewise captures a sense of the numinous:

In the first part of the story, Lovecraft hints at several possible identities for his story’s antagonist or--he is not clear even as to their number--antagonists. The villain could be a ghost, a demon, or some sort of monster with fangs and claws. He is ambiguous as to the creature’s origin as well. Local residents believe that it is associated with the Martense mansion atop Tempest Mountain. However, the narrator of the story, who is also the narrative’s protagonist, suggests that it may be linked to the weather--particularly, to the thunder. (The mansion and the weather, in fact, may themselves be connected in some way, as the house’s location, atop a mountain that takes its very name from a storm, or “tempest,” suggests.) Lovecraft’s multiplication of these possibilities is only one instance of such multiplications to be found in “The Lurking Fear.” On one occasion, the protagonist is certain that the creature is “organic,” or corporeal, but, later, he is just as sure that it is incorporeal. Obviously, it cannot be both, so which is it, tangible or intangible?

Another way by which Lovecraft multiplies possibilities (and therefore promotes ambiguity) in his tale is by suggesting several possibilities as to the creature’s point of origin. It is said to dwell in “some secret place.” Is it located in the house, in Jan Martense’s grave, in an underground tunnel, in the “odd mounds and hummocks of the region,” or elsewhere? Indeed, at times, it seems to drop out of the sky. Is it of an aerial nature? Neither the protagonist nor his companions, George Bennett and William Tobey, staying overnight in the mansion, know whether to expect the ghost, the demon, or the clawed monster to attack them from within or from without the house, so they are careful to suspend three rope-ladders from the ledge on the wall outside the room, one for each of them, in the event that the monster’s assault is from outside rather from inside the house. When the creature abducts Bennett and Tobey, it’s as if the men simply ceased to exist: they are simply gone, leaving “no trace, not even of a struggle,” and are “never heard of again.” Repeatedly, the reader wonders just what sort of threat it is that the protagonist faces. There are clues aplenty as to its possible identity, but none of them add up. All is confused and ambiguous. Therefore, and thereby, the story’s horror is increased, and its terror mounts.

As do Stoker, Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Stephen King, Dean Koontz, Bentley Little, Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, Dan Simmons, Robert McCammon, James Rollins, and other masters of the horror genre, past and present, Lovecraft both captures the sense of the numinous described by Otto and suggests the “Heavenly Hurt” spoken of by Dickinson--two characteristics that are, as much as the madness, monsters, mayhem, and terror, the hallmarks of horror fiction, representing “the certain slant of light” that illuminates the interests of its writers, readers, critics, and aficionados. In the pages (or upon the screen) of horror fiction, we are in the presence, often, of a “wholly other” force that is overpowering, urgent, and fascinating. Of course, it also happens, more often than not, to be destructive and deadly. It may be a horrible fate to encounter a demon after all, and, as Jonathan Edwards (and, less directly,

Stephen King), warns us, “It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God," to be sure.