Horror fiction often establishes a norm that it then violates. In Stephen King‘s fiction, the norm is usually everyday life as it transpires in small-town America. After setting the stage, often literally before the readers’ eyes, by having them follow a character on his or her way about town, delivering newspapers, jogging, or going about some other, ordinary, everyday task, and introducing them to several characters, King, at some point, upsets the applecart of everydayness by letting not the cat, but the monster, out of the bag. The ordinary laws of the universe no longer apply. At least, they don’t seem to apply.

When something spectacular enough to void the laws of nature occurs, readers may (and do) expect it to explain itself or, rather, they expect the protagonist to find the answers to the conundrum that the abrupt arrival of the uncanny represents. In fact, that’s the formula for much contemporary horror fiction, as I pointed out in a previous post:

1. All is well.

2. Something strange happens.

3. The protagonist learns the cause of the strange event (or series of events).

4. The protagonist uses his or her new-found knowledge to put things right again.

I also argued, as have others, that horror fiction is basically a conservative genre, because it is generally concerned with routing or destroying the monster and reestablishing order. However, in this post, as a sort of follow-up to the one in which I discuss the horror plot formula (“Horror Story Formulae”) and the one in which I talk about the loss of security in the face of evil and death (“Taking Away the Teddy Bear”), I would like to suggest, further, that the reestablishment of order renews readers’ sense of security, hope, and faith in the possibility of experiencing meaning in regard to their lives. Obviously, if the world makes no sense, if it is chaotic and capricious, nothing matters, and there is no hope of accomplishing anything that really counts.

Things that don’t fit the big picture (the model of reality that human beings have pieced together over millennia and continue to piece together in each new generation and age) threaten our security as a species, a nation, a community, or a family. The wholesale death that accompanied the spread of the bubonic plague during the Middle Ages threatened nations’ security, because the Black Death did not fit the picture of a world governed by a loving, all-powerful God. The Holocaust threatened the Jews’ security because the wholesale slaughter of their people did not fit with their understanding of themselves as God’s “chosen people.” A serial killer or a serial rapist threatens a community’s sense of security because a whole series of deaths or rapes in one’s own neighborhood suggests that the local police force is unable to protect the public; therefore, potentially anyone, male or female, is at risk of murder and any woman is at risk of being sexually assaulted. Extramarital affairs, among other things, threaten a family’s security because such behavior can destroy the family’s trust and psychological welfare.

Scientists supposedly revise their models of the universe, or nature, when discoveries warrant such revisions, replacing, for example, Newton’s theory of physics with Einstein’s theory of the same and foregoing Lamarckian evolutionary theory in favor of the Darwinian theory of evolution. By changing the big picture, scientists keep their understanding of the universe current with their discoveries of new facts. In theory, at least, and ideally, this is how scientists are said to work.

Scientists have faith that the universe is orderly, even if their own knowledge and understanding of this order is imperfect and changeable. It is, in fact, upon this bedrock of assumed certainty, of faith, that the scientific enterprise itself is based, for, without such assumed certainty with regard to the universe as orderly, no possibility of obtaining true and certain knowledge at any point would be possible. That doesn’t mean that one’s big picture is perfect; it will need correction from time to time.

The concept of the supernatural versus that of the paranormal clarifies such “paradigm shifts,” as the adaptations of scientific views concerning the universe have been called. At one time, ghosts, werewolves, zombies, and such were believed to be spiritual entities or monstrosities empowered by supernatural entities--beings beyond nature and outside the universe. Today, scientists, when they accept the notion that such phenomena exist at all (and many do not), consider them to be natural forces or entities which are, as yet, not understood, but which are, nevertheless, as natural, rather than supernatural, phenomena, understandable by science in principle.

Individuals have a harder time making such adjustments to their own big pictures. Often, the information they base their decisions--and, indeed, their very lives--on is fragmented, erroneous, partial, or untested. It is more a matter of faith and tradition, of custom and wishful thinking, than it is a matter of knowledge. It is disconnected and idiosyncratic. When new information or experiences challenge individual world views (if, indeed, such a lofty term can be applied to individuals’ often half-baked Weltanschauungs), individuals have trouble adjusting their thinking and adapting their beliefs so as to accommodate such challenges.

Some monsters challenge the world (the Martians in The War of the Worlds); others, nations Godzilla); and still others, communities (King Kong) or families (Cujo). Those that threaten the world or a nation challenge humanity on a global or national level; the others challenge humanity on a communal or familial level. In other worlds, the Martians in H. G. Wells’ novel challenge the security of a species which considers itself God’s gift to the universe, the “crown of creation” itself. If other intelligent life exists, human beings are not unique or even all that special--especially if the extraterrestrial species is technologically superior to the Earthlings whom they seek to conquer.

Human beings tend to congregate, to form cliques, families, communities, nations, and international alliances, mostly to increase their own chances for survival and to protect their group against others. A force that is not powerful enough to destroy the planet may be strong enough to destroy a nation, as the United States appeared to be, during World War II, when it dropped two atomic bombs on Japan. If the building of a nation, over a period of centuries, if not millennia, is no guarantee of safety or survival, nations have a right to tremble, as Japan does, in the shadow of the radioactive Godzilla.

Communities are based upon commonly shared characteristics (geographical location, if nothing else), common interests (the church, for example), or both. Depending upon the strength of the ties that bind such groups together, a community can withstand quite a challenge. New Orleans is regrouping after Hurricane Katrina, and the church has survived a variety of threats, internal and external, throughout much of the world, for thousands of years. However, a resurgence of the primitive, or primordial and instinctive drives that are normally repressed in the interest of the common good, can be potent enough to threaten a community, as King Kong, an embodiment of the primeval and bestial within human beings, almost succeeds in doing.

Likewise, a moral threat, such as adultery, symbolized by the attack of the rabid Saint Bernard in Cujo, or alcoholism and child abuse, the demons that haunt Jack Torrance in The Shining, can destroy one’s family.

There are plenty of threats, on every level of society and civilization, from peer pressure to nuclear annihilation. Security, which depends upon order, social, political, economic, cultural, psychological, moral, and otherwise, is subject to assault at any moment, and, indeed, it is under almost continuous attack. Whether one anchors his or her faith in God, in the human mind, in cultural and social traditions, in law, in parental love, or in some other seabed, sea serpents are apt to threaten such faith and to seek to overturn, or even to destroy, the order it tends to engender and to sustain.

Monsters shake up the big pictures that human beings piece together, on the individual, the familial, the communal, the national, and the global level. In doing so, as painful and as horrible as such “attacks” can be, the monsters do humanity a service. They expose the chinks in the armor of the individual, the familial, the communal, the national, or the international world views which, individually and collectively, comprise the beliefs, understandings, and values of humanity.

Like pain that alerts a person to a health problem, monsters alert people to moral, philosophical, theological, social, cultural, political, economic, or other problems that need to be addressed (or vanquished). If the monster doesn’t kill one (and, more often than not, it doesn’t kill the whole herd), it makes one stronger. By pointing out weaknesses in individual or communal beliefs, knowledge, or values, monsters help us to overcome them and, in the process, to transform fallacies, ignorance, and false values into the real deal, strengthening the bases of security upon which men and women build lives and societies of order, purpose, and significance, for the reestablishment of order which follows the vanquishing of the monster is a restoration of the faith which gives a sense of security to human beings who live in a dangerous world in an uncertain universe.

Wednesday, December 16, 2009

The Reestablishment of Order as the Restoration of Faith

Thursday, May 28, 2009

Modern Monsters

Before Christianity, paganism supplied humanity’s monsters. Initially, many were hybrids of wild animals and humans, among which were the centaur, the harpy, the lamia, the mermaid, the minotaur, the satyr, and the Sphinx. Most of them represented natural forces.“We have seen the enemy, and he is us.” -- Pogo

Christianity contributed the devil and his legions of lesser evil spirits, the demons.

Now that Christianity and other worldwide religions are in eclipse--in agricultural and progressive nations, at least--writers of horror fiction have had to find their monsters elsewhere.

Science has been a major source of modern horror fiction’s nightmarish creatures. Other worlds have supplied writers with menacing demons, extraterrestrial diseases, and a variety of paranormal threats including clairvoyants, telekinetic travelers, time travelers, homicidal cyborgs, and rampaging robots.

Psychology has also been a source for many of the inner demons that haunt the world of the self. Sigmund Freud contends that modern monsters are aspects of ourselves which we have, as it were, cut off and cast out. They are embodiments, in other words, of those elements of ourselves that we repress.

As a species, we have gone from the Other as a duality of the bestial and the human to the Other as a supernatural seducer, tempter, and deceiver to the Other as the rejected elements of a would-be self--from natural to supernatural to psychological. In the process, the monster has gone from the general to the specific.

Edgar Allan Poe showed us the way, substituting the madman for the demon, ghost, vampire, werewolf, or other paranormal or supernatural threat. However, there is another source for the modern monster: the Self--or, rather--the wannabe Self which we repress. At first, such a source might seem too finite for the task we have set it, which is nothing less than that of being the maker of all things destructive, menacing, destructive, evil, and lethal. We need not worry, however, about whether our supply of monsters will peter out. There are as many inner demons as there are individual men, women, and children.

Just the list of inner demons which have found expression as objective Others in the work of Stephen King suggests the breadth of the range of possibilities for such embodiments of iniquity. His novels have depicted demons of child abuse and religious fanaticism (Carrie), narcissistic self-indulgence and hypocrisy (Needful Things), alcoholism and psychosis (The Shining), spousal abuse (Rose Madder), adultery (Cujo), government abuse of its citizenry (Firestarter), and a host of other Others.

To develop the modern monster, one must become adept at seeing the repressed Other in oneself and in other people, for, today, the repressed is the monstrous.

Two clues are rationalization and hypocrisy. We want to be perfect, even though we know that we are not, and cannot be, without fault. Therefore, we tend to deny what is obviously true to others about behaviors which we may do but certainly not want to admit that we do them.

Instead, we lie to ourselves about our behavior, make excuses for our conduct, and deny that we have acted in anything but an admirable and proper manner. What we would condemn in others, we accept, or even celebrate, in ourselves. By identifying behaviors which we rationalize or would condemn in others but approve in ourselves, we can identify the inner demons both of ourselves and others.

Sunday, April 26, 2009

The Value of Literature

Wednesday, March 25, 2009

Sensory Links

The size of the sensory homunculus’ hands, tongue, ears, nose, and eyes represents the relative space that human body parts occupy on the somatosensory cortex and the motor cortex and the relative sensitivity of each of the senses of touch, taste, hearing, smell, and vision, respectively.

In first five paragraphs of Monster, Frank Peretti uses sound and sight to link paragraphs, which not only provides transitions that might otherwise not exist, except as chronological associations among the incidents of action represented by the author’s descriptions, but also lends to the action itself a sense of immediacy, creating the illusion that the reader him- or herself is, as it were, on the scene. Whether through auditory, visual, olfactory, gustatory, or tactile sensations, such references to the senses and their perceptions can link paragraphs for any writer, whether Peretti or you, whether the fiction is of the horror or another genre. Therefore, it is worthwhile to consider how Peretti accomplishes this feat, quoting a few paragraphs from his novel. In doing so, we start with the first paragraph and quote the next ten, each in turn, as well, bolding the auditory sensory links in blue and the visual sensory links in green (which are neither bolded nor colored in the novel itself, of course):

The Hunter, rifle in his hands, dug in a heel and came to a sudden halt on the game trail, motionless, nearly invisible in a thicket of serviceberry and crowded pines. He heard something.

The first rays of the sun flamed over the ridge to the east, knifing through the pine boughs and morning haze in translucent wedges, backlighting tiny galaxies of swirling bugs. Soon the warming air would float up the draw and the pines would whisper like distant surf. But in the lull between the cool of night and the warmth of day, the air was still, the sounds distinct. The Hunter heard his own pulse. The scraping of branches against his camouflage sleeves was crisp and brilliant, the snapping of twigs under his boots almost startling.

And the eerie howl was clear enough to reach him from miles away, audible under the sound of the jays and between the chatterings of a squirrel.

He waited, not breathing, until he heard it again: long, mournful, rising in pitch, and then holding that anguished note to the point of agony before trailing off.

The Hunter’s brow crinkled under the bill of his cap. The howl was too deep and guttural for a wolf. A cougar never made a sound like that. A bear? Not to his knowledge. If it was his quarry, it was upset about something.

And far ahead of him.

He moved again, quickstepping, ducking branches, eyes darting about, dealing with the distance.

Before he had worked his way through the forest another mile he saw a breach in the forest canopy and an open patch of daylight through the trees. He was coming to a clearing.

He slowed, cautious, found a hiding place behind a massive fallen fir, and peered ahead.

Just a few yards beyond him, the forest had been shorn open by a logging operation, a wide swath of open ground littered with forest debris and freshly sawn tree stumps. A dirt road cut through it all, a house-sized pile of limbs and slash awaited burning, and on the far side of the clearing, a hulking yellow bulldozer sat cold and silent, its tracks caked with fresh earth. A huge pile of logs lay neatly stacked near the road, ready for the logging trucks.

He saw no movement, and the only sound was the quiet rumble of a battered pickup truck idling near the center of the clearing.The book goes on, for approximately 425 more pages, so we will part company with it here, and see what we can fathom as to the narrative and rhetorical purposes that Peretti’s sometimes simultaneous, sometimes alternating use of mostly auditory and visual sensory links within and among these paragraphs suggests.

He waited, crouching, eyes level with the top of the fallen tree, scanning the clearing, searching for the human beings who had to be there. But no one appeared and the truck just kept idling.

His gaze lifted from the truck to the bulldozer, then to the huge pile of logs, and then to the truck again where something protruding from behind the truck’s front wheels caught his eye. He grabbed a compact pair of binoculars from a pocket and took a closer look.

The protuberance was a man’s arm, motionless and streaked with blood.

Often in the novel, as in its opening paragraphs, sounds precede sights, reversing the order in which human beings normally perceive their environment, for we are much more dependent upon sight than hearing; sight, it could be said, is our preferred sense. It is the one to which we look, if such a pun may be pardoned, before we look to any of the others.

Hearing and touch tell us much, and we are also highly dependent upon them, of course, and less so upon smell and taste (although, once the novel’s protagonist, Rebecca [“Beck”] Shelton, is abducted by the monster of the novel’s title, she is surprised as to how much she becomes dependent upon her sense of smell as well as those of her sight and hearing). In the big pine woods, to which Beck, her husband Reed, and their friends have come to undergo a few days of survival training, sight is greatly reduced by the thick foliage of the dense stands of trees, and normal perception is put, as it were, off balance. (Even the hunter frustrates vision by wearing camouflage.)

Moreover, with the sense of hearing heightened and the sense of sight impeded, the auditory perceives nothing reassuring; far from it, the sounds of the forest are unfamiliar (“He heard something,” but he doesn’t know what, nor do we, the readers), and even the sense of sound, like that of sight, is reduced and obstructed: it is often reduced to a whisper or a lull, or silenced altogether. What is heard distinctly is the terrifying howling of “something” that, as Peretti is careful to inform us, is unlikely to be any familiar forest predator, whether wolf, cougar, or bear. The implication is that, whatever the howling “something” is, it is far worse even than these predatory beasts.

The deep forest makes the use of the senses upon which human beings most depend--sight and sound--problematic at best, increasing their ignorance and subjecting them to more potential menace. As such, the reduction of the senses, referenced within and between the novel’s opening paragraphs by the sensory links of sound and sight, of the auditory and the visual, may be a metaphor for the ignorance of humanity itself, especially in regard to knowledge that is assimilated by means of the senses--in other words, empirical knowledge, the type upon which scientists, including the evolutionary biologists who are the novel’s antagonists as much as the monster of its title, depend.

If the senses are undependable; if they are all but shut down, as it were, at times, then, perhaps, the sciences that are built upon them and its theories, including the theory of evolution, are tentative at best and prone to error. Certainly, this is the view of the creationist scientist Dr. Michael (“Cap”) Capella and his “lovely Coeur d’Alene Native American” wife, Sings in the Morning, or “Sing.” Ironically, both she and the novel’s other Native American character, a tracker, believe in the reality of the monster that abducts Beck; it is the immigrant European, the white man, who disbelieves, despite Caucasian scientists’ attempt to create, a la Dr. Moreau, a hideous new species of human-animal hybrids.

The undependability of the senses, especially those of sight and hearing, seems to reinforce the irony of empirical scientists who are skeptical of divine creation, having neither the eyes, as it were, to see the error of their theory nor the ears to hear the creationists’ criticisms of their fallacious reasoning. If anything, it is faith, not empirical knowledge or even reason, that must save the day.

It is good writing to link paragraphs by the use of words and phrases that appeal to sight and sound, both within and between, paragraphs, but it is superb writing to make such a device thematic as well as merely rhetorical, as Peretti does, creating of such links a metaphor that echoes and reinforces the novel’s very theme, expressed explicitly, several times by Dr. Capella in the course of the novel, and, quite succinctly, by one of Cap’s colleagues, Dr. Emile Baumgartner: “Tampering with DNA is like a child trying to fix a high-tech computer with a toy hammer. It’s always am injury, never an improvement, and we have boxcar loads of dead, mutated fruit flies and lab mice to prove it.”

Empirical science, sense-based, as it is and must be, has its limitations, even aided by reason, for the senses are limited, often inaccurate, sometimes deceived, and cannot penetrate beyond mere appearances. To pretend to understand the origin of the universe and the consequences that flow from the uncaused cause of the Big Bang is not only absurd, but it is also dangerous, Peretti suggests--as dangerous as being alone in a dense forest in which there be monsters that one cannot see or hear--until, perhaps, it is too late.

Friday, December 12, 2008

Fallacious Horrors

A nice bit of pseudo-logic, to be sure, but this one, reported in the same article, is even more unseemly and amusing:

Ad hoc hypotheses are common in defense of the pseudoscientific theory known as biorhythm theory. For example, there are very many people who do not fit the predicted patterns of biorhythm theory. Rather than accept this fact as refuting evidence of the theory, a new category of people is created: the arhythmic. In short, whenever the theory does not seem to work, the contrary evidence is systematically discounted.

Friday, August 29, 2008

Teleology and Horror

The evolution of hair, of eyes, of noses, of mouths, of sex and the sexes--these are fascinating topics, and they point, each one, to sometimes disturbing, sometimes revolting, but always fascinating, moments in which something original arose out of nature or creation, usually in response to a need. But in anticipation of a need to come?

Impossible, one might suppose--but what if evolution isn’t blind; what if it’s an instrument of an all-knowing, all-seeing God? In other words, what if evolution is teleological? (The very word “teleology,” of course, itself breeds horror among atheistic evolutionists, in whose number Charles Darwin did not, by the way, count himself any more than did the Catholic theologian and evolutionist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin.)

Teleology, in relation to evolution, suggests that organisms develop along lines that are purposeful and goal-directed. Teleologists argue that, rather than being determined by its environment and the stimuli that it provides, the organism and its organs are determined by its (and their) purpose. For example, people have physical senses because they need to see, hear, touch, taste, and smell; they don’t sense things because they have senses.

The view of metaphysical naturalism that atheistic evolutionists hold and the view of ontogenesis that teleologists hold have moral implications concerning minerals, plants, animals, and humans. The former assumes that organisms are what they are and that they are neither good nor evil nor better nor worse than one another. The latter view is often the basis for the concept of lesser and greater organisms which each have a correspondingly lower or higher place in the cosmic chain of being. To personalize these views, one might say that Lucretius and Aldous Huxley hold the former view and that Aristotle and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin hold the latter view.

Nothing in the body is made in order that we may use it. What happens to exist is the cause of its use. -- Lucretius. (In other words, function follows form)

Nature adapts the organ to the function, and not the function to the organ. -- Aristotle. (In other words, form follows function.)

These contrasting views of evolution frequently fuel speculative fiction, especially the science fiction branch of it, but they have also occasionally driven horror fiction, especially if one holds, as it seems easy enough to do, that human beings are natural organisms that have evolved to a point that is sufficient for them to begin, through such means as agricultural hybridization, eugenics, genetic engineering, and cloning, to direct evolution, for even adherents of metaphysical naturalism must find it difficult to deny any possibility of purposeful and goal-directed activity to human behavior in its entirety. We have become the gods that nature, perhaps blindly, or that God, with forethought, intended, us to become, and we are now capable, to whatever limited and clumsy degree, of determining the direction and the purpose of nature, as many a horror story involving the experimental procedures of mad scientists have indicated.

If Harry Harrison’s Deathworld trilogy is an example of the function-follows-form theory of evolution (the whole planet and everything in it has evolved to survive at the expense of all other plants and animals), the Terminator film series (especially the original) is an example of the form-follows-function theory of evolution (cyborgs have been created to seek and kill a specific individual and anyone or anything else that gets it its way, and they even build themselves). Both result in scary worlds in which one is apt to end up dead. Which method of execution seems scarier may come down to two questions:

- Would you rather be killed by a natural, organic monstrosity that responds to the stimulus of your presence by killing you or by a technological monstrosity that kills you because it’s programmed to do so?

- Is there an intelligence operating the universe (that is, nature) behind the scenes, so to speak and, if so, is this intelligence gracious or cruel, loving or malevolent?

Tuesday, August 5, 2008

Nothing Gets Between a Monster and Its Genes

Why did you throw the jack of hearts away? It was the only card in the deck I had left to play.

-- The Doors

As far as I know, it was Stan Lee of Marvel Comics who introduced comic book readers to the idea of genetic mutation as the cause of superhuman traits that could convert an otherwise normal human being into a godlike character who could use his or her powers for good or evil. In doing so, Lee inserted a joker into the deck of fate. (Actually, since quite a few of the superhuman powers of Marvel’s superheroes and villains were the results of such mutations, Lee inserted almost as many jokers into the deck as there were regular, or “normal” cards.) Since there have been a rash of motion pictures based upon Marvel Comics (and, for that matter DC Comics) of late, many of the characters in which possess powers courtesy of various genetic mutations, it seems unnecessary to review these powers. For those who are unfamiliar with how the Marvel Comics’ powers-by-genetic-mutation technique works, a brief summary is in order. According to Marvel, the Celestials, an extraterrestrial race, visited the Earth a million or so years ago for the express purpose of monk eying with human deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), implanting a substance, the X-Gene, which facilitated beneficial genetic mutations in the implanted hosts, resulting, in more extreme cases, in such characters as those who swelled the ranks of the The Uncanny X-Men (the first issue of which appeared in (1963) and the Brotherhood of Mutants. For years, this was Marvel Comics’ favorite explanation for superheroes’ and villains’ great powers, explaining the abilities of such characters as Apocalypse, Beast, Cyclops, Iceman, Marvel Girl, Professor X, Storm, Wolverine, and many others. Collectively, such characters, in the Marvel universe, are also known as homo superior.

What have they done to the Earth? What have they done to our fair sister? Ravaged and plundered and ripped her and but her, Stuck her with knives in the side of the dawn, Tied her with fences and dragged her down. . . .

-- The Doors

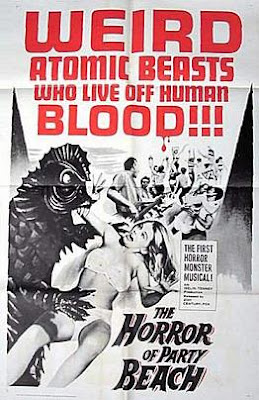

Even before Lee introduced genetic mutations as a cause of characters’ special effects, so to speak, horror fiction monsters were spawned, as it were, as a result of genetic mutations. (Most appeared in decidedly bad--no, make that terrible--B films.) Among such creatures are the sea monsters of The Horror of Party Beach (1964) (human skeletons radiated by atomic waste that leaks from an undersea drum, a peril of humans’ disdain for ecological purity); the monster of Godzilla (1954) (an undersea creature that had an origin identical to the monsters of Party Beach); The Being (1983) (a monster who was spawned by the wastes in a disposal dump); Creatures from the Abyss (1994) (teen love makers, whose decision to make out aboard an abandoned yacht equipped with a bio lab causes them to become infected with radioactive plankton); C.H.U.D. (1984) (people become monsters as a result of toxic waste dumped in the Big Apple’s sewers); It’s Alive (1974) (a mutant baby is sought by the authorities, who don’t intend to nurture it); and many others.

Even before Lee introduced genetic mutations as a cause of characters’ special effects, so to speak, horror fiction monsters were spawned, as it were, as a result of genetic mutations. (Most appeared in decidedly bad--no, make that terrible--B films.) Among such creatures are the sea monsters of The Horror of Party Beach (1964) (human skeletons radiated by atomic waste that leaks from an undersea drum, a peril of humans’ disdain for ecological purity); the monster of Godzilla (1954) (an undersea creature that had an origin identical to the monsters of Party Beach); The Being (1983) (a monster who was spawned by the wastes in a disposal dump); Creatures from the Abyss (1994) (teen love makers, whose decision to make out aboard an abandoned yacht equipped with a bio lab causes them to become infected with radioactive plankton); C.H.U.D. (1984) (people become monsters as a result of toxic waste dumped in the Big Apple’s sewers); It’s Alive (1974) (a mutant baby is sought by the authorities, who don’t intend to nurture it); and many others.

Why the popularity of genetic mutations as an explanation for the acquisition of superhuman or monstrous abilities? There seem to be several reasons:When the still sea conspires an armor And her sullen and aborted Currents breed tiny monsters True sailing is dead.

--The Doors

- When horror films and Marvel Comics introduced the idea, genetic mutation as the result of changes to an organism’s DNA was relatively new, or cutting edge, as was the idea for genetic engineering. However, eugenics was already a well-known concept and attempts at engineering an ideal race were tried by mad scientists during the years of Nazi Germany. (The concept of what constitutes such a race--and, indeed, the very idea of a “master race”--is, or can be, in itself a monstrous notion and involves the same hubris that was demonstrated by Victor von Frankenstein and Dr. Moreau in earlier times.) Writers are always looking for new ideas because new ideas, in and of themselves, are intriguing.

- The origins of good and evil tend to be limited to such causes as divine creation, demonic possession or manipulation of human beings, madness, improper behavior (sin, crime, or anti-social conduct), birth defects, extraterrestrial intervention in human affairs, scientific and technological manipulations of nature and human nature, and the like. When a new cause for good or evil (and not just abilities) is unearthed, it’s apt to be popular and persistent among authors, especially of fantasy, science fiction, and horror, including writers of comic books that involve or are based upon such genres.

- Genetic mutations are real! They actually happen in nature and can be engineered in scientific labs by real-life “mad scientists.” Of course, any scientist worth his or her weight in neutronium will tell one that such mutations, rather than benefiting an organism, are more likely to have a negative, or even fatal, effect upon it. That’s a small detail often overlooked by comic book, fantasy, science fiction, and horror writers, although some do capitalize upon this fact, using genetic mutations as a way of effecting madness or physical deformity that, in return, has monstrous results.

- Genetic mutations that result from scientific and technological manipulations of nature replace miracles as a means of effecting changes to DNA and, therefore, to human nature and behavior, allowing human beings, in their arrogance, to wrest creation from the creator, putting people in charge of a world they never made but one that they are hot to remake in their own image and likeness. From a religious point of view, such arrogance, or pride, is blasphemous and can be expected to result is sure punishment. From a secular point of view, such hubris is presumptuous and, perhaps, premature, and will likely bring about, in its results, its own penalty, for, after all, it’s nice to fool with Mother Nature and it’s even worse to fool around with her.

He was a monster, dressed in black leather; She was a princess, Queen of the highway. -- The Doors

Sunday, June 22, 2008

Explanations For Evil

Horror maestro Stephen King

One way to consider a lot of the explanations horror fiction has put forth for the evils that this genre of fiction depicts (and sometimes celebrates) is to consider some of the major novels of Stephen King (stories with identical causes are excluded, as are those for which no more than a mere mention is given on King’s website:

What makes one explanation for the bizarre incidents and situations in a horror story acceptable to an audience while another explanation for such happenings is not? Here are a few possibilities:

- Magical Thinking. No, we don’t live in a pre-scientific age during which magical thinking is part and parcel of one’s worldview, but, were we to be honest, we’d have to admit that, even in the twenty-first century, after having put a man on the moon, we still believe in magic, at least on a gut level. How else do we explain such notions as penis envy, the Oedipus complex, phallic women, and Rorschach inkblots? How else do we understand the way television signal transmissions and receptions operate or gravity or thermodynamics? The scientists among us may be able to answer some of the questions we have concerning the universe and our place in it, but they also admit that many of their statements are analogical or metaphorical, rather than literal, meaning that, beyond a certain level, they have no idea what they’re talking about. As Sir William Frazier points out in The Golden Bough, there are basically two types of magic: sympathetic, or imitative, magic and the magic of correspondence. Both rely upon magical thinking--the belief that non-scientific relationships among phenomena can be of such a nature that one somehow (mysteriously) affects or controls another. Sympathetic magic rests upon the premise that one can obtain the results that he or she imitates. Want to cause someone to suffer a heart attack? Stick a pin into voodoo doll’s chest. Correspondence rests upon the premise that one can influence what occurs to one person, place, or thing by manipulating another person, place, or thing to which the former is somehow related. Astrology (“as above, so below”) is a perfect example: the positions of heavenly bodies affect and determine one’s fate. According to The Skeptic’s Dictionary, sympathetic magic is probably behind such beliefs as those pertaining to “most forms of divination. . . voodoo. . . psychometry. . . psychic detectives. . . graphologists. . . karma. . . synchronicity. . . homeopathy” and, of course, magic itself. This list indicates that, pre-scientific age or not, ours is still one in which there are a great many believers in magic and the thinking that underlies it.

- Recognition. Emotion, rather than logic, can be sufficient grounds for many of us to accept an explanation as appropriate and satisfying. To be emotionally acceptable to us, the explanation for the horror story’s uncanny events must suggest that the truth that the main character learns about him- or herself and/or the world, including others, is a natural, even inevitable, consequence of his or her experience. In other words, given what has happened to him or her, the protagonist has no other alternative but to draw the conclusions that he or she draws concerning the cause of these events--and the cause will have to do with his or her own behavior. Carrie’s explanation for the bizarre incidents that take place in the novel (and the movie based upon the novel) is acceptable to its readers (and viewers) because Stephen King ties the incidents to the existential and psychological states of the protagonist whose telekinesis, in service to her damaged emotions, self-image, and thinking, causes the murder and mayhem that she unleashes upon her tormentors, almost as an afterthought, once she realizes that, despite appearances to the contrary, nothing has changed, and she is still the target of other people’s prejudices and hatred.

- Tradition, or Familiarity. Once a type of monster gains acceptance from the general public, usually as a result of its traditional use, its reference as the cause of the story’s eerie events is accepted for the sake of the narrative, even if (as is likely) it is rejected on the rational level. In other words, readers and viewers are willing to suspend their disbelief. This tendency on the part of readers and moviegoers to accept traditional monsters as the causes of bizarre incidents is the basis for the use of demons, ghosts, mummies, vampires, werewolves, and the like as causal agents in horror stories. Familiarity may breed contempt, but it can also generate a grudging acceptance of causality which, otherwise, would be summarily dismissed. “Oh, it’s a werewolf. Okay, then.”

- Analogy. To be persuasive as a cause of the horror story’s horrific events, an explanation must be detailed. There must be a series of correspondences between the alleged cause and the alleged effects. In other words, one must be able to infer, on the basis of the similarities between two things that these same two things are alike in yet other ways (“A” is like “B.” “B” has property “C.” Therefore, “A” has property “C.”) Analogies are notoriously unreliable and often fallacious, but that doesn’t stop them from being persuasive to many, and, in fiction, what counts is their persuasiveness as causes. Writers of fiction are not especially concerned at all points (or maybe at any point) as to whether statements are true; they’re concerned with entertaining their audience, and, to this end, with whether their audience will “buy” a particular explanation of their action’s incidents and situations, bizarre and uncanny or otherwise.

- Integrality. The explanation, whatever it is, must not be haphazard. It must not be tacked on, seemingly at the last minute, simply to explain (or to explain away) the story’s eerie occurrences. Instead, the explanation must be essential. Without the explanation, the series of odd incidents and situations would make no sense (not that they need to make a whole lot of sense, necessarily, even with the explanation in place). For the explanation to be acceptable or plausible, the writer must give hints early and often as to the nature of the cause behind the effects. In The Taking, Dean Koontz, early on, plants the idea that the bizarre actions in his novel may be the effect of Satan’s return to earth, and this possibility is repeated in the thoughts of the protagonist concerning her sorrow for past moral offenses she’s committed and her hope for forgiveness and reconciliation and by the narrative’s end, in which she becomes a new Eve, carrying within her womb the first of humanity’s new humanity. At the same time, however, the possibility that the novel’s bizarre events are the effects of reverse-terraforming by an advance party of invading aliens purposely detracts from this, the actual, cause. By contrast, in The Resort, Bentley Little merely mentions an older resort near the one in which his story’s action take place and implies, without ever saying exactly how, that the former resort is somehow associated with the contemporary one. There are no specific correspondences, no detailed links, between the two (the older one of which, in fact, has burned down). There is only the suggestion, without a supporting context supplied by a pertinent back story or other means of exposition. The result is the deux ex machina that Aristotle so much abhorred and rejects in his Poetics as emotionally and dramatically unconvincing.

Dean Koontz and Trixie

A horror story stands or falls, to a large extent, by its explanation for the evil, bizarre events and situations that occur during much of the story. The explanation may not pass scientific muster, but it must at least pass the emotional and dramatic smell tests of the audience if it is to be satisfying and, therefore, successful. In the final analysis, the inexplicable must be explained, if only in theory.Sunday, May 18, 2008

Fictional Stories as Thought Experiments

According to James Robert Brown’s article in the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, thought experiments are “devices of the imagination used to investigate the nature of things.” (This definition makes fiction itself a grand and complex thought experiment, we may argue.) Among the more famous of such experiments are “Newton’s bucket, Maxwell’s demon, Einstein’s elevator, Heisenberg’s gamma-ray microscope, and Shrodinger’s cat”:

Schrödinger's cat. . . does not show that quantum theory (as interpreted by Bohr) is internally inconsistent. Rather it shows that it is conflict with some very powerful common sense beliefs we have about macro-sized objects such as cats. The bizarreness of superpositions in the atomic world is worrisome enough, says Schrödinger, but when it implies that same bizarreness at an everyday level, it is intolerable. . . . Einstein's elevator showed that light will bend in a gravitational field; Maxwell's demon showed that entropy could be decreased. . . . Newton's bucket showed that space is a thing in its own right; Parfit's splitting persons showed that survival is a more important notion than identity when considering personhood (“Thought Experiments”).

Thought experiments are just as important to philosophy, Brown observes, as they have proven to be to science: “Much of ethics, philosophy of language, and philosophy of mind is based firmly on the results of thought experiments,” and, to illustrate his observation, he identifies several of the more important philosophical thought experiments: “Thompson's violinist, Searle's Chinese room, Putnam's twin earth, Parfit's people who split like an amoeba.” (We might add the example of the philosophical zombie, discussed in a previous post, as well.)

Describing an early thought experiment, which appears in Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura, Brown identifies three “common features of thought experiments”: “We visualize some situation; we carry out an operation; we see what happens.”

Like special effects, thought experiments can be conducted even when actual conditions or moral considerations make an actual experiment impossible or objectionable.

Occasionally, thought experiments might help to revolutionize scientific theory as well, according to Thomas Kuhn: “a well-conceived thought experiment can bring on a crisis or at least create an anomaly in the reigning theory and so contribute to paradigm change” (Brown). For additional benefits from, and some objections that scientists and philosophers have advanced concerning the use of thought experiments, those which were conducted by the likes of Newton and Einstein notwithstanding, check out Brown’s article (liked above).

We suggest that, before science, there were also thought experiments, called fiction (or, before fiction was recognized as invented rather than of an inspired or an empirical origin), as myths, folktales, and legends. Ancient Greek (and Egyptian and Norse) myths were of special significance in establishing the ways by which storytellers and their audiences (pretty much all of any society of the time) understood, thought about, and interpreted themselves and the world around them. Such stories, from time to time, also sought to investigate the possibilities of human existence and of nature. At such times as these, the myths became what we could call narrative or dramatic thought experiments. Even today, stories, especially in the fantasy and science fiction genres, continue to pose and conduct thought experiments about all aspects of human existence and nature itself. Horror fiction also conducts such experiments on occasion (as the popularity of the mad scientist, for example, suggests).

Brown’s analysis of Lucretius’ thought experiment led him to posit three features characteristic of all thought experiments: “We visualize some situation; we carry out an operation; we see what happens.” The what-if mode of envisioning stories (an abbreviated way of saying “What might happen if”), common, once again, to fantasy and science fiction (and to alternate history stories) virtually demands such an approach, at least at times, but horror fiction and literature in other genres can do so, too. In horror fiction, we might ask, “What if a chemical compound could, when ingested, cause abnormally large growth in the animals that had consumed it?” The result of this visualization of a specific situation, carried out by the telling of the tale, might be H. G. Wells’ The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth, in which the result is shown to be an imminent war between the haves (the “Children of the Food” and the have-nots (the “Pygmies”) to determine whether growth shall win out over the non-growth of the status quo.

Unhampered by modern science’s knowledge of natural laws, Greek myths (as well as those of other ancient nations) asked what-if questions with the abandonment that can result only from the naiveté of the abysmally ignorant:

- What if a person (or maybe a demon) could assume whatever shape it chose, for as long as it chose to do so?

- What if a person were of gigantic size and had a single eye in the middle of his forehead?

- What if a creature were half-man and half-horse?What if a creature were half-woman and half-fish?

- What if a horse, having wings, could fly?

- What if men and women lived forever and could rule over various aspects of nature?

- What if one man had the strength of twenty men?

- What if women could fight as good as--no, better than--men?

- What if a woman had a baby after being raped by the devil?

- What if God mated with a mortal woman?

- What if a house were haunted by a vengeful ghost?

Horror fiction asks similar (or, indeed, on occasion, identical) questions, but with an emphasis on the horrific:

- What if a person (or maybe a demon) could assume whatever shape it chose, for as long as it chose to do so? (It)

- What if a demon could animate a corpse? (Dracula)

- What if the spirits of the dead exist in some shadowy manner and can interact with humans? (The Turn of the Screw)

- What if a scientist could cause a body constructed of parts from corpses to live again? (Frankenstein)

- What if a man could change into a wolf and back again into a man? (The Howling)

- What if a woman, raped by the devil, gave birth to a son? (Rosemary’s Baby)

- What if a child abuser, torched by his victims’ parents, returned as a vengeful bogeyman? (Nightmare on Elm Street) \

- What if an extraterrestrial female came to earth, seeking a mate? (Species)

- What if vampires came to a small town in modern America? (‘Salem’s Lot)

- What if a modern-day Cinderella with telekinetic powers had a terrible time at the ball? (Carrie)

- What if myths were based upon true incidents or creatures? (Dominion)

- What if the earth were invaded by a Martian military force (The War of the Worlds)

- What if a scientist tried to create an intelligent, hybrid human-animal species? (The Island of Dr. Moreau)

- What if a brain could survive inside a decapitated head on life-support? (The Brain That Wouldn’t Die)

- What if an extraterrestrial creature, trapped in a block of ice, were thawed out by a group of scientists operating an arctic research laboratory? (The Thing)

These and countless other what-if questions allow writers to envision a situation that is improbable or impossible in nature or because of moral concerns, carry out a thought experiment (writing or reading the resulting story), and see what happens. Different genres appeal to different concerns and respond to different issues:

- Adventure appeals to the desire to escape and to explore new worlds.

- Detective and mystery stories appeal to the desire to solve a puzzle and to see that justice is served.

- Fantasy appeals to the desire for experience wonder and awe.

- Horror appeals to the desire to survive against seemingly impossible odds and to endure great losses and suffering.

- Science fiction appeals to one’s innate curiosity about the world and the desire to discern the realities behind appearances.

- Romance appeals to the desire to meet and marry Mr. Right.

- Westerns appeal to the desire for law, order, and justice, especially for the underdog.

Each genre of fiction is apt to pose imaginary (and imaginative) situations that, peculiarly appropriate to their own purposes, allow writers and readers to “carry out an operation” and “see what happens” with regard to the genres’ own special interests and concerns. As much as the myths, legends, and folktales of yesteryear, contemporary fiction, including horror stories, remains a vast and complex series of never-ending thought experiments that can draw upon not only science and philosophy but also theology, art, and all other cultural realms and practical aspects of human existence.

Source cited

Brown, James Robert. "Thought Experiments.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2007.

Saturday, May 17, 2008

Going Through the Motions, or The Physics of Fiction

- An object at rest remains at rest, or if moving remains moving in a straight line if no external forces act upon it.

- If an external force is applied, the object’s motion will change in either magnitude or direction, and the rate of change of the motion (its acceleration) when multiplied by the object’s mass is equal to the applied force.

- For every force applied to an object there is an equal and opposite force exerted back by the object (24-25).

Let’s apply these laws of motion to the horror story plot (or, for that matter, any other type of plot).

According to Gustav Freytag, an incident in the story’s plot sets everything that follows it into motion. This incident, called the inciting moment, is like a spark that starts a fire or, in terms of Newton’s laws of motion, it is the external force that changes the plot-as-object’s motion, causing it to take a new direction. Were it not for the inciting moment, the plot would continue forward, in a straight line, so to speak, rather than changing direction as it begins its upward climb which commences what Freytag calls the plot’s rising action.

The third law of motion is also useful as a means of envisioning what writers, literary critics, and readers call conflict, for it is the “force applied” by the protagonist to the antagonist, or “object,” countered by the “equal and opposite force exerted back” by the antagonist that balances the story’s action (at least until the turning point, a second inciting moment of sorts, which intervenes to set the plot off in a new, downward direction, as it were, Freytag’s falling action.

As Kakalios points out, the second law of motion (“If an external force is applied, the object’s motion will change in either magnitude or direction, and the rate of change of the motion (its acceleration) when multiplied by the object’s mass is equal to the applied force”) can be represented by the mathematical formula F = ma, wherein F = force, m = mass, and a = acceleration (25). (Acceleration differs from velocity, Kakalios reminds his readers. The former refers to the change in speed over time, whereas the latter refers to the change in speed over distance [30].) Mass is simply a measure of how many atoms make up an object. A piece of plastic is made up of relatively few atoms, whereas lead is comprised of many more atoms, packed, as it were, in an equal amount of space. The more atoms-per-space (mass) and the greater the rate of acceleration, the more force results. In terms of story plotting, we mentally replace atoms with narrative incidents (or, in description, perhaps with action verbs and shorter sentences). The more incidents, action verbs, and sentences we “pack” into a passage, the greater its force, or narrative effect, upon the reader. It seems that Edgar Allan Poe has something similar to this concept, minus the physical laws of motion, in mind, when he argues, in “The Philosophy of Composition,” that a shorter story, especially one that can be read in “a single sitting,” without interruption, has a greater effect upon its readers than a longer story which is, in effect, simply a series of shorter stories told successively and related to one another through cause and effect. To make a story more horrifying, speed up the action (writing action verb-packed short sentences in a rapid-fire series of narrative incidents); to slow the pace and the story’s effect (horror), slow down the same process.

It seems that, understood figuratively, Newton’s laws of motion apply to plotting horror fiction (and other literary genres) as much as they do to physical and mechanical motion.

Source cited

Kakalios, James. The Physics of Superheroes. New York: Gotham Books, 2005.

Thursday, February 14, 2008

Alternative Explanations, Part I: Demons and Ghosts

The type of info you’ll need to know depends upon the type of paranormal or supernatural force or entity that is (allegedly) involved. Is it a demon? A ghost? A clairvoyant or a telekinetic person? Someone who’s adept at levitation whom other characters just don’t want hanging around all the time? Vampires? Werewolves? Zombies? An extraterrestrial species? Cthuthlu? Something else entirely?

Let’s take a look at some of the paranormal and supernatural classics and mainstays of the horror genre and the alternative explanations for them.

Okay, demons. First, what are they supposed to be? Evil spirits, right? But spirits of what? Dead animals? Dead people? Hats and shoes? Or are they a breed apart? Biblical traditions maintain that demons are fallen angels--angels, in other words, who rebelled against God, perhaps under the leadership of Satan, and were punished by being cast out of heaven and into hell. From time to time, they may visit the earth to tempt human beings for fun and profit (their victims’ eternal damnation, which would swell the population of hell).

Apparently, demons--or, quite a few of them, anyway--can possess people, and they may do so either individually or in groups. William Peter Blatty’s novel The Exorcist and the movie based upon it are supposedly based upon a true exorcism. The movies The Possession of Emily Rose and Requiem are both allegedly based upon another real-life case. They are interesting to study because each suggests a different approach that the skeptic character in your story could take in debunking the existence of demons--at least those who possess people.

The case upon which The Exorcist is supposedly based is nothing more than the result of exaggerations of the incidents that are alleged to have occurred in the actual case or sheer inventions, some contend. According to “The Real Story Behind the Exorcist,” “virtually all of the gory and sensational details were embellished or made up. Simple spitting became Technicolor, projectile vomiting; (normal) shaking of a bed became thunderous quaking and levitation; the boy’s low growl became a gravelly, Satanic voice.”

The Exorcism of Emily Rose and Requiem rely upon mischaracterizing mental illness and its effects as being demonic possession and its effects, critics argue. Adopting this approach to debunk diagnoses of demonic possession, the horror story’s skeptical character would say that the supposedly possessed person is mentally ill and susceptible to suggestions on the part of the exorcist:

“. . . exorcisms have been (and continue to be) performed, often on emotionally and mentally disturbed people. . . . Most often, exorcisms are done on people of strong religious faith. To the extent that exorcisms ‘work,’ it is primarily due to the power of suggestion and the placebo effect. If you believe you are possessed, and that a given ritual will cleanse you, then it just might.”

Mark Opsasnick’s thorough, detailed debunking, “The Haunted Boy: The Cold, Hard Facts Behind the Story that Inspired The Exorcist,” explains the exaggeration-invention approach to creating demons and demonic possession. The Skeptic’s Dictionary lists it and numerous other books and articles that question, evaluate, and reject spurious claims to demonic possession. (The Skeptic’s Dictionary, by the way, is an excellent basic source for all alternative explanations of allegedly paranormal and supernatural and, indeed, otherworldly, or extraterrestrial, phenomena).

Thus, the horror story’s skeptical character can explain demons and demonic possession by suggesting that demons and demonic possession are concocted out of exaggerations and inventions, the misdiagnoses of mental illness as demonic possession and susceptibility of the apparently possessed religious victim, or both.

- They’re made of ectoplasm.

- Their presence is discernable by psychics.

- They make the air cold because they’re energy magnets, and thermal energy is energy. (One might say that ghosts were once environmental threats, except that, with global warming underway, they may now be ecological heroes.)

- They tend to be rather camera shy, but other equipment seems to register phantom phenomena.

- They sometimes haunt places or people or both with which or whom they were associated in the days of their incarnation, perhaps for revenge or for no other reason that they don’t know they’re dead (hard to imagine) or how to get to the great beyond.

- They can walk through solid objects, such as walls or your Aunt Betty.

- Some, known as poltergeists, are especially noisy and destructive.

What’s our skeptic’s likely answers to such claims? Ghosts may also be products of hallucinations, especially during sleep paralysis. Most ghost stories rely upon anecdotal evidence, which is “always incomplete and selective.” (For a critique of anecdotal evidence, check out “anecdotal [tensional] evidence”.)

According to The Skeptic’s Dictionary, skeptics have found cheesecloth an excellent “ectoplasm” material for use at séances conducted by mediums (sort of psychic midwives), especially if the medium who delivered the ghosts, so to speak, was a woman. Scientific American established a committee to investigate one medium’s psychic abilities, Harvard psychology professor William McDougall summarizing one of his group’s findings: “There is good evidence that "ectoplasm" issues, or did issue on some and probably all occasions [from] one particular 'opening in the anatomy' (i.e., the vagina).” She refused to be strip-searched before séances and would not “perform in tights.” Another skeptic “offers a much simpler explanation for the production of ectoplasm. Have your husband sit next to you during the séance. Make sure he has stuffed his shirt or pants with stuff to slip to you under the table when the lights are out.”

According to The Skeptic’s Dictionary, the big chill that is said to accompany the presence of ghosts is likely to result from drafts of air. Some noise may also be attributed to such ventilation. The activity of mechanical equipment, such as extraction fans, may also create air currents that produce odd sounds. Ghosts supposedly prefer night to day and darkness to light because it’s easier to see them in the dark than in daylight, since their ectoplasm is supposedly see-through. Our skeptic might counter this claim by suggesting another reason for ghosts’ alleged preference for darkness: it’s much easier to deceive others under conditions of darkness, too, than it is in broad daylight or in a well-lighted room.

While few ghosts worthy of the film have appeared on camera, some ghost hunters claim to have caught evidence of them on such equipment as “tape recorders, EMF detectors, video cameras with night vision, metal detectors.” Skeptics might question whether this--or any--equipment has been designed to detect ghosts, noting that, just because such equipment may look scientific, doesn’t mean that it is, and that certainly “tape recorders, EMF detectors, video cameras with night vision, metal detectors.” are not designed to detect the spirits of the deceased. Live Science finds ghost hunters’ supposedly scientific equipment questionable and challenges the claims its users have made concerning the equipment’s detection of ghosts. After pointing out that “the equipment is only as scientific as the person using it,” Benjamin Radford, the author of “The Shady Science of Ghost Hunting,” queried an equipment supplier as to the “scientific rationale. . . behind the equipment he sold” and received this surprisingly candid answer:

“At a haunted location," Cook said, "strong, erratic fluctuating EMFs are commonly found. It seems these energy fields have some definite connection to the presence of ghosts. The exact nature of that connection is still a mystery. However, the anomalous fields are easy to find. Whenever you locate one, a ghost might be present.... any erratic EMF fluctuations you may detect may indicate ghostly activity. . . . There exists no device that can conclusively detect ghosts."

Radford observes, with logic fatal to ghost hunting, “The supposed links between ghosts and electromagnetic fields, low temperatures, radiation, odd photographic images, and so on are based on nothing more than guesses, unproven theories, and wild conjecture. If a device could reliably determine the presence or absence of ghosts, then by definition, ghosts would be proven to exist.”

As Radford points out in the same article, statistics also cast doubt upon ghosts who are said to haunt their murderers: “If murder victims whose killings remains unsolved are truly destined to walk the earth and haunt the living, then we should expect to encounter ghosts nearly everywhere. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, roughly a quarter of all homicides remains unsolved each year,” and “There are about 30,000 homicides in America each year.”

He also questions how it is that ghosts wear clothing: “Do shoes, coats, hats, and belts also have souls? Logically, ghosts should appear naked.”

“On the Subject of Ghosts,” an article by Michael LaPointe, the “laws laid down by Sir Isaac Newton” make it “impossible for a non-physical entity to simultaneously walk upon surfaces and pass through solid objects, such as doors and walls; if a being is applying force to the ground in order to propel themselves, they therefore can’t pass through other solids without falling through the floor.” One has a choice, it seems. He or she can believe the anecdotal evidence of a haunted soul who sees ghosts do such things or the eminent scientist Isaac Newton, who says that neither ghosts nor anything else in the universe can perform such impossible feats. The party with whose claim one sides suggests much about his or her faith, whether it’s in the supernatural or the scientific.

As The Skeptic’s Dictionary points out, poltergeists generally turn out to be not mischievous, noisy nuisances of the spirit world but, rather, flesh-and-blood pranksters of a juvenile nature, whose antics are coupled, perhaps, with “perceptual misinterpretations, e. g., seeing things move that never moved or attributing sounds or movement of inanimate objects to spirits when one can't detect the source” or air drafts and other natural causes.

In one case, a woman named Mrs. Connolly found:

“A imitation fireplace and a couple of chairs overturned in the living room. Such things went on for four days. A building inspector suggested the problem might be coming from the fireplace, so Mrs. Connolly hired someone to put a protective covering over the chimney top. "From that moment on, the objects stayed put". . . . Mrs. Connolly was not a superstitious woman and attributed the events to powerful drafts swirling down the chimney and disturbing objects in their path. When confronted with poltergeist activity one should not rule out such natural factors as drafts of wind.”

Children are the poltergeists in another account of alleged poltergeist activity that is recounted in The Skeptic’s Dictionary:

“William Roll investigated the Resch case and declared it authentic. In 1984, Tina was 14 years old and living in Columbus, Ohio. Newspaper reports testified to her chaotic household where telephones would fly, lamps would swing and fall, all accompanied by loud noises. James Randi also investigated the case and found that Tina was hoaxing her adoptive parents and using the media attention to assist her quest to find her biological parents.

A video camera from a visiting TV crew that was inadvertently left running, recorded Tina cheating by surreptitiously pulling over a lamp while unobserved. The other occurrences were shown to be inventions of the press or highly exaggerated descriptions of quite explainable events. (Randi 1995).”

Even mere forgetfulness can explain the movement of objects by ghosts. People sometimes move an object, such as a set of keys, from one location, such as their bedroom dresser, to another, such as the kitchen counter, and, forgetting having done so, attribute the object’s relocation to the ghost that they believe must be haunting their homes.

But what about well-known accounts of ghostly visitations and haunted houses, such as Amityville? A couple of articles have appeared on the Live Science website that debunk Amityville: “The Truth Behind Amityville” and “The Truth Behind the Amityville Horror.” They’re a bit too involved and lengthy to summarize here; that’s why you’re directed there.

In Part II of “Alternative Explanations,” we’ll consider how your horror story’s skeptical character might debunk claims about other paranormal and supernatural phenomena.

Paranormal vs. Supernatural: What’s the Diff?

Sometimes, in demonstrating how to brainstorm about an essay topic, selecting horror movies, I ask students to name the titles of as many such movies as spring to mind (seldom a difficult feat for them, as the genre remains quite popular among young adults). Then, I ask them to identify the monster, or threat--the antagonist, to use the proper terminology--that appears in each of the films they have named. Again, this is usually a quick and easy task. Finally, I ask them to group the films’ adversaries into one of three possible categories: natural, paranormal, or supernatural. This is where the fun begins.

It’s a simple enough matter, usually, to identify the threats which fall under the “natural” label, especially after I supply my students with the scientific definition of “nature”: everything that exists as either matter or energy (which are, of course, the same thing, in different forms--in other words, the universe itself. The supernatural is anything which falls outside, or is beyond, the universe: God, angels, demons, and the like, if they exist. Mad scientists, mutant cannibals (and just plain cannibals), serial killers, and such are examples of natural threats. So far, so simple.

What about borderline creatures, though? Are vampires, werewolves, and zombies, for example, natural or supernatural? And what about Freddy Krueger? In fact, what does the word “paranormal” mean, anyway? If the universe is nature and anything outside or beyond the universe is supernatural, where does the paranormal fit into the scheme of things?

According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word “paranormal,” formed of the prefix “para,” meaning alongside, and “normal,” meaning “conforming to common standards, usual,” was coined in 1920. The American Heritage Dictionary defines “paranormal” to mean “beyond the range of normal experience or scientific explanation.” In other words, the paranormal is not supernatural--it is not outside or beyond the universe; it is natural, but, at the present, at least, inexplicable, which is to say that science cannot yet explain its nature. The same dictionary offers, as examples of paranormal phenomena, telepathy and “a medium’s paranormal powers.”

Wikipedia offers a few other examples of such phenomena or of paranormal sciences, including the percentages of the American population which, according to a Gallup poll, believes in each phenomenon, shown here in parentheses: psychic or spiritual healing (54), extrasensory perception (ESP) (50), ghosts (42), demons (41), extraterrestrials (33), clairvoyance and prophecy (32), communication with the dead (28), astrology (28), witchcraft (26), reincarnation (25), and channeling (15); 36 percent believe in telepathy.

As can be seen from this list, which includes demons, ghosts, and witches along with psychics and extraterrestrials, there is a confusion as to which phenomena and which individuals belong to the paranormal and which belong to the supernatural categories. This confusion, I believe, results from the scientism of our age, which makes it fashionable for people who fancy themselves intelligent and educated to dismiss whatever cannot be explained scientifically or, if such phenomena cannot be entirely rejected, to classify them as as-yet inexplicable natural phenomena. That way, the existence of a supernatural realm need not be admitted or even entertained. Scientists tend to be materialists, believing that the real consists only of the twofold unity of matter and energy, not dualists who believe that there is both the material (matter and energy) and the spiritual, or supernatural. If so, everything that was once regarded as having been supernatural will be regarded (if it cannot be dismissed) as paranormal and, maybe, if and when it is explained by science, as natural. Indeed, Sigmund Freud sought to explain even God as but a natural--and in Freud’s opinion, an obsolete--phenomenon.

Meanwhile, among skeptics, there is an ongoing campaign to eliminate the paranormal by explaining them as products of ignorance, misunderstanding, or deceit. Ridicule is also a tactic that skeptics sometimes employ in this campaign. For example, The Skeptics’ Dictionary contends that the perception of some “events” as being of a paranormal nature may be attributed to “ignorance or magical thinking.” The dictionary is equally suspicious of each individual phenomenon or “paranormal science” as well. Concerning psychics’ alleged ability to discern future events, for example, The Skeptic’s Dictionary quotes Jay Leno (“How come you never see a headline like 'Psychic Wins Lottery'?”), following with a number of similar observations:

Psychics don't rely on psychics to warn them of impending disasters. Psychics don't predict their own deaths or diseases. They go to the dentist like the rest of us. They're as surprised and disturbed as the rest of us when they have to call a plumber or an electrician to fix some defect at home. Their planes are delayed without their being able to anticipate the delays. If they want to know something about Abraham Lincoln, they go to the library; they don't try to talk to Abe's spirit. In short, psychics live by the known laws of nature except when they are playing the psychic game with people.In An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural, James Randi, a magician who exercises a skeptical attitude toward all things alleged to be paranormal or supernatural, takes issue with the notion of such phenomena as well, often employing the same arguments and rhetorical strategies as The Skeptic’s Dictionary.

In short, the difference between the paranormal and the supernatural lies in whether one is a materialist, believing in only the existence of matter and energy, or a dualist, believing in the existence of both matter and energy and spirit. If one maintains a belief in the reality of the spiritual, he or she will classify such entities as angels, demons, ghosts, gods, vampires, and other threats of a spiritual nature as supernatural, rather than paranormal, phenomena. He or she may also include witches (because, although they are human, they are empowered by the devil, who is himself a supernatural entity) and other natural threats that are energized, so to speak, by a power that transcends nature and is, as such, outside or beyond the universe. Otherwise, one is likely to reject the supernatural as a category altogether, identifying every inexplicable phenomenon as paranormal, whether it is dark matter or a teenage werewolf. Indeed, some scientists dedicate at least part of their time to debunking allegedly paranormal phenomena, explaining what natural conditions or processes may explain them, as the author of The Serpent and the Rainbow explains the creation of zombies by voodoo priests.

Based upon my recent reading of Tzvetan Todorov's The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to the Fantastic, I add the following addendum to this essay.

According to Todorov:

The fantastic. . . lasts only as long as a certain hesitation [in deciding] whether or not what they [the reader and the protagonist] perceive derives from "reality" as it exists in the common opinion. . . . If he [the reader] decides that the laws of reality remain intact and permit an explanation of the phenomena described, we can say that the work belongs to the another genre [than the fantastic]: the uncanny. If, on the contrary, he decides that new laws of nature must be entertained to account for the phenomena, we enter the genre of the marvelous (The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre, 41).Todorov further differentiates these two categories by characterizing the uncanny as “the supernatural explained” and the marvelous as “the supernatural accepted” (41-42).

Interestingly, the prejudice against even the possibility of the supernatural’s existence which is implicit in the designation of natural versus paranormal phenomena, which excludes any consideration of the supernatural, suggests that there are no marvelous phenomena; instead, there can be only the uncanny. Consequently, for those who subscribe to this view, the fantastic itself no longer exists in this scheme, for the fantastic depends, as Todorov points out, upon the tension of indecision concerning to which category an incident belongs, the natural or the supernatural. The paranormal is understood, by those who posit it, in lieu of the supernatural, as the natural as yet unexplained.

And now, back to a fate worse than death: grading students’ papers.

My Cup of Blood

Anyway, this is what I happen to like in horror fiction:

Small-town settings in which I get to know the townspeople, both the good, the bad, and the ugly. For this reason alone, I’m a sucker for most of Stephen King’s novels. Most of them, from 'Salem's Lot to Under the Dome, are set in small towns that are peopled by the good, the bad, and the ugly. Part of the appeal here, granted, is the sense of community that such settings entail.

Isolated settings, such as caves, desert wastelands, islands, mountaintops, space, swamps, where characters are cut off from civilization and culture and must survive and thrive or die on their own, without assistance, by their wits and other personal resources. Many are the examples of such novels and screenplays, but Alien, The Shining, The Descent, Desperation, and The Island of Dr. Moreau, are some of the ones that come readily to mind.

Total institutions as settings. Camps, hospitals, military installations, nursing homes, prisons, resorts, spaceships, and other worlds unto themselves are examples of such settings, and Sleepaway Camp, Coma, The Green Mile, and Aliens are some of the novels or films that take place in such settings.

Anecdotal scenes--in other words, short scenes that showcase a character--usually, an unusual, even eccentric, character. Both Dean Koontz and the dynamic duo, Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, excel at this, so I keep reading their series (although Koontz’s canine companions frequently--indeed, almost always--annoy, as does his relentless optimism).

Atmosphere, mood, and tone. Here, King is king, but so is Bentley Little. In the use of description to terrorize and horrify, both are masters of the craft.