Copyright 2012 by Gary L. Pullman

Note: This post assumes that you have seen the movie The Exorcist (1973). If you have not, Wikipedia offers a fairly detailed, accurate summary of the plot.

Results of a 2009 Pew

Research Center survey

indicate that 33 percent of scientists believe in God; another 18 percent “believe

in a universal spirit or higher power.” However, 83 percent of the

American populace as a whole believes in God and 12 percent “believe

in a universal spirit or higher power.” As far as disbelief is

concerned, 41 percent of scientists do “not believe in God or a

higher power” and 4 percent of the general public share their view. (A 2017 poll places the number of Americans who "do not believe in any higher power/spiritual force" at 10 percent.)

Source: fanpop.com

According to some evolutionary psychologists, faith developed like any other evolved adaptation, or trait: it promotes human survival and reproduction. Faith, proponents of this point of view argue, is comforting, provides community cohesion, and offers a basis for ethics and “higher moral values.” Others regard faith as a spandrel or an expatation, that is, a “by-product of adaptations” that is useful for reinforcing the authority and status of the clergy and for providing emotional support for the faithful in times of trouble. As is true of many of the arguments of evolutionary psychology, these claims are controversial, keeping critics aplenty busy on both sides of the discussion.

Source: pinterest.com

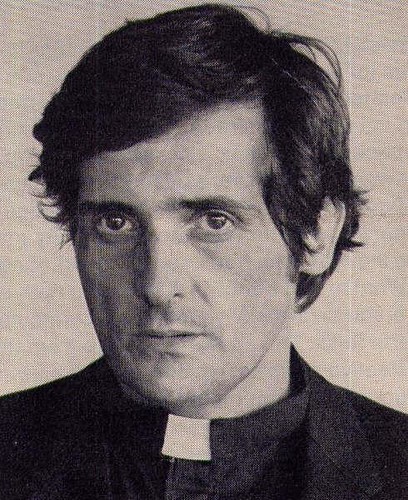

The Exorcist offers a concrete example of faith in action in Father Karras's exorcism of the demon (or demons) who allegedly possess Regan MacNeil.

Source: flickriver.com

The priest's faith may provide some emotional comfort for him, but, it is obvious to the movie's audiences, his faith does not extinguish his feelings of guilt regarding his perceived neglect of his ailing mother, and faith as such offers little immediate comfort or reassurance to any of the other characters, with the possible exception of Father Merrin, who is killed early in the movie.

Although Karras's faith may hold the “community” of Regan's family together, his life as a priest, although it may assist some members of the wider world, seems to offer little benefit to his own life or to that of the Church he serves.

Source: pinterest.com

Karras's faith does seem to cause him to judge, condemn, and feel revulsion toward the demons who allegedly possess Regan, and he frequently rebukes them, denouncing their behavior as impious, blasphemous, and sacrilegious, without passing judgment on the girl herself: he hates the sin, not the sinner.

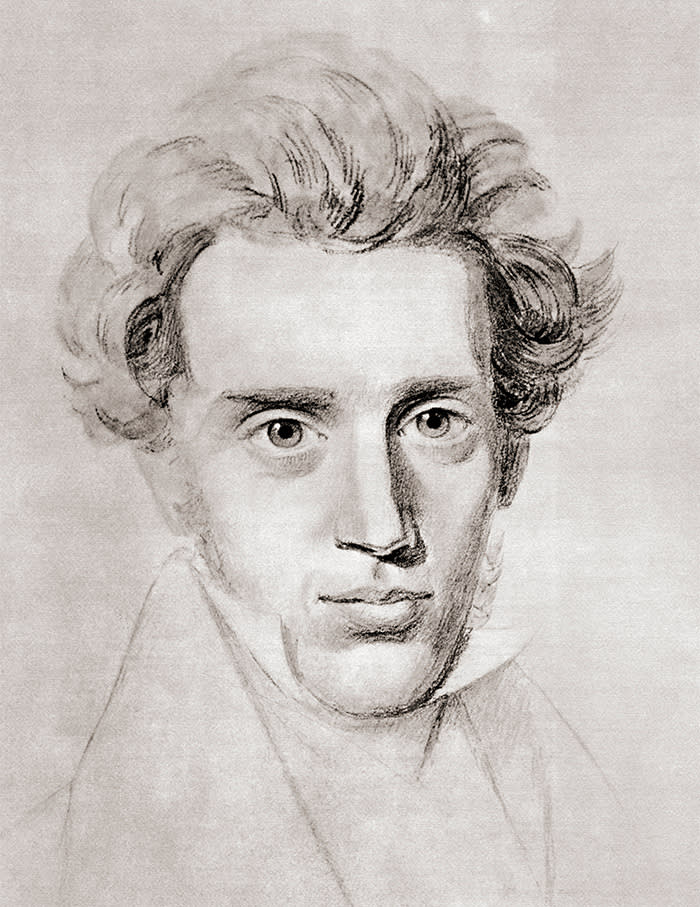

Throughout the movie, Karras experiences a crisis of faith. The ordeal that his mother faced during her illness, his own callous treatment of his mother (as he sees it); the apparent indifference and cruelty of human beings for one another; the sins that he encounters daily, both as a man and a priest; and the evil he witnesses as he seeks to exorcise the demons that have possessed the child he seeks to deliver suggest to him that, either he has lost his faith and, indeed, might never have had a true basis for belief in and trust of God; God has abandoned him; or, worst of all, God is “dead” or never existed to begin with, except as a myth. In any case, faith does not appear to have any true survival value—until Karras makes what Soren Kierkegaarad calls “the leap of faith.”

Close to despair, Karras does not despair. Close to renouncing his faith in God, Karras remains faithful to God. He shows that he is, indeed, the man of faith whom he has long professed to be. He has been discouraged. He has had doubts. He has entertained disbelief. However, to save Regan, he invites her demons into himself and then leaps out of her bedroom window, falling to his death. In doing so, he delivers her from the evil spirits that possessed her. But Karras accomplishes more as well; he remains true to his own beliefs, to his calling, to himself, to God.

Source: ft.com

According to the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, in Kierkegaard's thought, “the choice of faith is not made once and for all. It is essential that faith be constantly renewed by means of repeated avowals of faith.” Despite his doubts, Karras has constantly renewed his faith. Despite his temptation to despair, Karras does not despair. Close to renouncing his faith in God, Karras remains faithful to God. In each of these decisions, he maintains his faith and, therefore, himself.

As Kierkegaard points out, “in order to maintain itself as a relation which relates itself to itself, the self must constantly renew its faith in 'the power which posited it.'” This “repetition” of his faith sustains Karras, allowing him to deliver Regan. Initial appearances aside, the priest's faith, as it turns out, has tremendous survival power, both for Karras himself, who, in remaining true to his faith in God, remains true to himself, and for Regan, whom he delivers from her demons.

Source: listal.com

For those who do believe in God, even if they represent a minority of the populace as a whole, their faith delivers them (and, indeed, many others whom they aid). Their faith makes them whole, even if they are broken; sets them free, even if they are possessed; enables them to reach—and even sometimes save—others, believers and disbelievers alike, by their example. Even if their accomplishments were to be attributed solely to their belief in belief, to their faith in faith, and to their trust in trust, rather than to an objective, real, personal God, these amazing and extraordinary accomplishments stand, testaments to the assertion that the trait of faith has survival value.