Copyright 2010 by Gary L. Pullman

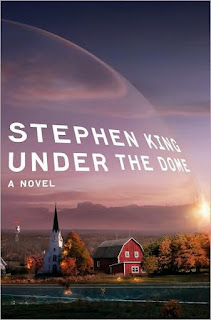

To say that the ending to

Under the Dome is anticlimactic is an understatement. To say, moreover, that it is sophomoric is to put the matter mildly. It is both a letdown and a disappointment.

King’s characters have suffered, most of them greatly; many of them have died. Were they real, flesh-and-blood people, the survivors would be traumatized, probably for life, by the death and destruction they have seen. Their friends, neighbors, and families, children included, are dead; their homes and businesses have been destroyed; their lives are in ruins. Why? What has caused this wholesale loss?

It could be argued that much of the death and destruction stems from the machinations of the greedy, self-serving, power-mad, criminal Big Jim Rennie and his cohorts. In the guise of doing what is best for the town, Big Jim has caused more than a good deal of mischief. He has abused his constituents, neglected the community’s real needs, and capitalized by pandering to the townspeople's weaknesses and fears. He has profited from the manufacture and distribution of methamphetamine; he has ordered others to commit arson and violence; he has encouraged the incitement of a riot; he has murdered people with his own hands and has covered up the murders of others by his son. He has set friend against friend and neighbor against neighbor. His ordering of a raid against the drug addicts who hold hostage the propane tanks that he stole from the local hospital and other businesses to fuel his illegal drug operation resulted in a conflagration that decimated the homes and businesses of the thousands who also perished in the inferno, burned alive. Throughout the crisis that began with the descent of the dome and the many others that he himself created, Big Jim prospered while others suffered and died.

The townspeople are not blameless; both as children and as adults, they, too, have participated in the evils that befall themselves and others. Even the heroes and heroines of King’s novel have past sins for which to atone.

There are few true innocents under the dome, apart from infants such as Little Walter Bushey and the canines Horace, Clover, and Audrey.

Some citizens are guiltier than others: Big Jim Rennie, Junior Rennie, Pete Randolph, Georgia Roux, Frank DeLesseps, Melvin Searles, Carter Thibodeau, Stewart and Fern Bowie, Roger Killian, Joe Boxer, Phil Bushey, Lester Coggins, and Sam Verdreaux.

A few, the children, are innocent or relatively innocent: Joe McClatchey, Norrie Calvert, Benny Drake, Judy and Janelle Everett, Ollie and Rory Dinsmore, Alice and Aidan Appleton. However, as Julia Shumway’s account of the “watershed moment” in her own girlhood indicates, even children are capable of cruelty and evil.

Other characters are not developed enough for the reader to determine their guilt or innocence: Rose Twitchell, Anson Wheeler, Marty Arsenault, Rupert Libby, Stacey Moggin, Ron Haskell, Ginny Tomlinson, Dougie Twitchell, Gina Buffalino, Harriet Bigelow, Jack Cale, Johnny Carver, Lissa Jamieson, Claire McClatchey, Alva Drake, Tony Guay, Pete Freeman.

Finally, still other characters are guilty not because of corruption or meanness, but because of personal weaknesses or a significant, but lone, moral failure: Andréa Grinell, Andy Sanders, Dale Barbara, Angie McCain, Dodee Sanders, Freddy Denton, Piper Laurie, Rusty and Linda Everett, Romeo Burpee, Samantha Bushey, Stubby Norman, Brenda Perkins, Thurston Marshall, Carolyn Sturges.

King is careful, in most cases, to indicate his characters’ various moral offenses or failings, which include drug addiction, alcoholism, child abandonment, sexual promiscuity, adultery, henpecking, negligence, a reluctance or unwillingness to involve oneself in social and political conflicts and the duties of citizenship, assault (physical, sexual, and verbal), murder, malfeasance, theft, arrogance, a greater concern for economic advancement than for ending human suffering.

King suggests a practical means of distinguishing good from evil. Moral actions help others (or, presumably, oneself); immoral actions hurt others (or, presumably, oneself). In addition, in quoting Jimi Hendrix, the author suggests another, more nebulous criterion for determining what behavior is good and desirable and what behavior is bad and undesirable: “When the power of love overcomes the love of power, the earth will know peace.” For the most part, his characters’ deeds and misdeeds fit into one or the other of these classification systems. Clearly, Big Jim’s actions are motivated by a love of power rather than by the power of love; likewise, his behavior has a harmful, more than a helpful, effect on others, including his son (and, ultimately, himself). In other cases, the classifications are not as clear cut, but the moral theory that King suggests seems applicable to their conduct, nevertheless. Human behavior’s effects, whether good or evil, desirable or undesirable, right or wrong, continue beyond individuals' lives, effecting the lives of their posterity. Police Chief Howard Perkins’ collection of evidence against Big Jim certainly influenced the events that transpired in the town long after his own demise. Likewise, the lesson in humility that Julia Shumway learned when she was abused as a child by her classmates at the Commons’ bandstand had a definite effect upon her behavior in begging the alien child for mercy at the end of the novel and was critical in the salvation of the remnant of the townspeople.

In his exploration of moral and immoral behavior and the effects of both upon the human community, both present and future, King’s novel offers penetrating insights and a good deal of food, as it were, for thought and is a rewarding read. The story itself is also a fairly suspenseful, almost always intriguing, and entertaining experience. Like most of King’s other novels, this one is apt to stay with the reader, to become part of who he or she is. This is certainly a test of effective, even of good, literature.

The test, perhaps, of which characters King finds worthy of salvation is indicated in his catalogue of final survivors, which appears on page 1066 of his novel. If this is true, one can extrapolate from what the omniscient narrator and the characters themselves have revealed concerning these characters’ past deeds and misdeed:

(On page 997, according to the omniscient narrator, “on Saturday morning. . . “just thirty-two” survivors remained of the town’s population:

- Aidan Appleton

- Alice Appleton

- Dale Barbara

- Harriet Bigelow

- Gina Buffalino

- Romeo Burpee

- Little Walter Bushey

- Ernest Calvert

- Joanie Calvert

- Norrie Calvert

- Ollie Dinsmore

- Alva Drake

- Benny Drake

- Linda Everett

- Janelle Everett

- Judy Everett

- Rusty Everett

- Pete Freeman

- Tony Guay

- Lissa Jamieson

- Piper Libby

- Thurston Marshall

- Claire McClatchey

- Joe McClatchey

- Big Jim Rennie

- Julia Shumway

- Carter Thibodeau

- Ginny Tomlinson

- Dougie Twitchell

- Rose Twitchell

- Sam Verdreaux

- Jackie Wettington

By page 1066, seven others (Aidan Appleton, Ernest Calvert, Benny Drake, Thurston Marshall, Big Jim Rennie, Carter Thibodeau, and Sam Verdreaux) have died, bringing the total number of survivors to twenty-five.

- Alice Appleton (child)

- Dale Barbara (Army colonel; cook)

- Harriet Bigelow (elderly woman)

- Gina Buffaloing (volunteer nurse)

- Romeo Burpee (department store owner)

- Little Walter Bushey (baby)

- Joanie Calvert (mother)

- Norrie Calvert (child)

- Ollie Dinsmore (child)

- Alva Drake (mother)

- Linda Everett (police officer)

- Janelle Everett (child)

- Judy Everett (child)

- Rusty Everett (physician’s assistant)

- Pete Freeman (news photographer)

- Tony Guay (sports reporter)

- Lissa Jamieson (librarian)

- Piper Libby (pastor)

- Claire McClatchy (mother)

- Joe McClatchy (child)

- Julia Shumway (newspaperwoman)

- Ginny Tomlinson (nurse)

- Dougie Twitchell (nurse)

- Rose Twitchell (restaurant owner)

- Jackie Wetting ton (police officer)

Barbie did not stop the torture of war prisoners that his team was interrogating in Fallujah. Romeo is an adulterer. Initially, Linda was willing to believe false testimony and bogus evidence against Barbie. As a boy, Rusty tortured ants, burning them alive. Piper still preaches, although she has become an atheist. As a child, Julia was arrogant toward her classmates, thinking herself superior to them. The other adults are unlikely to be blameless (what adult is?), but the narrative does not provide enough information concerning their backgrounds to identify any specific wrongdoing on their part. As the abuse that Julia suffered at the hands of her classmates shows (and as the torture of the residents of Chester’s Mill by the young alien also indicates), children can also be guilty of wicked, cruel behavior, but, again, the reader is not made privy to enough information regarding the children who survive to know exactly what wrongs they may be guilty of having committed. Because of Julia’s humiliation, she learned humility, and she pleads with the young alien who has imprisoned her and the other residents of Chester’s Mill under the dome to release them so that they may live out their “little lives” in a scene reminiscent of both her own abuse (as punishment for her arrogance toward her fellow students) and Rusty’s realization that ants have “little lives” that should not be wantonly destroyed any more than any other life. The alien’s sparing of them may be regarded as a sort of redemption for them, a pitying, if not a forgiveness, of them. Just as one of Julia’s tormentors returned and gave her a sweater to wear home, the extraterrestrial child removes the dome to allow her and her fellow survivors to live out their “little lives,” an act that the novel’s protagonist attributes not to love, but to pity: “Pity was not love, Barbie reflected. . . but if you were a child, giving clothes to someone who was naked had to be a step in the right direction” (1072).

King’s morality (helping others = good; hurting others = evil) is a survivors’ morality. It does not depend upon God or love or anything else but the assumption that helping others is morally proper, whereas hurting them is morally improper. All of the survivors, despite the horrific experiences they have undergone and whatever their faith, if any, may be, or their philosophy of life, may agree to accept this most basic definition of righteousness. It is virtuous to help and depraved to hurt others. King’s characters pass or fail the morality test depending upon whether they help or hurt their friends, neighbors, and families. In quoting Jimi Hendrix (“when the power of love overcomes the love of power, the earth will know peace”) and in suggesting that, while it is not love, pity for another is “a step in the right direction,” King implies that, beyond the simple morality of survivors, there is a deeper, more mature standard for determining right and wrong, or good and evil, which is whether one loves and is loving; he also suggests that, for the majority of human beings, who are morally immature, such an understanding awaits the humility and wisdom that may follow from horrific and traumatic suffering.

The disappointment is the cause of the dome or, at least, of its descent. Earlier in the novel, several possible causes for this phenomenon were suggested, including that the dome was a living entity, that it is the invention of rogue scientists, that it is a means of terrorist attack, that it is a government experiment using the Chester’s Mill residents as guinea pigs, and that it is the work of extraterrestrials possessed of superior technological sophistication. It turns out to be a toy of sorts, and the ones who use it, children. Granted, they are children of extreme intelligence, but children, nevertheless, with no more compassion or love for the human beings whom they torture than children who set fire to anthills have for the ants they thereby kill. The problem with this premise is that it creates a context--a dome, if one pleases--in which adult behavior is perceived by immature, alien beings. They are cosmic creatures, but without the wisdom and love of the omniscient, omnipresent, and omnipotent God in whose existence Piper Libby comes to disbelieve and, finally, to deny, accepting, in its stead, a belief in the aliens:

Piper Libby. . . was thinking of all those late-night prayers to The Not-There. Now she knew that had been nothing but a silly, sophomoric joke, and the joke, it turned out, was on her. There was a There there. It just wasn’t God (934).

The absurdity of a pastor rejecting the traditional idea of God for one in which the deity is a group of extraterrestrial “kids” is ludicrous. For greater minds than that of King’s own, such as those of St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, Karl Barth, Soren Kierkegaard, and Paul Tillich, to mention but a few, such a revision of faith would be not only ludicrous, but also blasphemous. By reducing the complexity of human behavior, predicated as it is, to some degree, upon free will, to conduct that parallels the simple, instinctive, and probably completely determined behavior of ants is itself ridiculous, but then to make human existence a plaything of amoral and sadistic (albeit cosmic) children is to vacate any suspension of disbelief the reader is capable of extending to the author’s work. A belief in the God of the Jews, the Christians, or the Muslims is a basis for understanding human nature; substituting extraterrestrial children for such a deity is simply incredible and silly. Under the Dome is an entertaining novel, to be sure, but, one may be confident in the belief that neither William Golding nor T. S. Eliot need fear having their work confused with King’s novel, the master of horror’s allusions to their respective novel and poem notwithstanding.

NOTE: Be sure to visit

Chester's Mill's website!