Copyright 200 by Gary L. Pullman

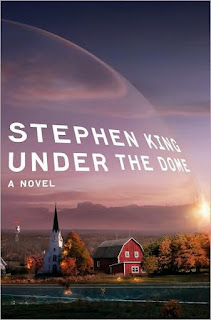

The “Survivors” section of Stephen King’s latest novel, Under the Dome, starts on an ominous note:

Only three hundred and ninety-seven of The Mill’s two thousand residents survive the fire. . . . By the time night falls. . . there will be a hundred and six.Ollie Dinsmore, equipped with a tank of oxygen and an oxygen mask takes refuge inside his farm’s potato cellar from the firestorm sweeping through the dome.

When the sun comes up on Saturday morning. . . the population of Chester’s Mill is just thirty-two (997).

Sam Verdreaux, also equipped with oxygen, makes his way toward the McCoy cabin atop Black Ridge, lamenting his role in initiating the riot at Food Town and breaking Georgia Roux’s jaw.

Big Jim Rennie and Carter Thibodeau wait out the firestorm inside the Town Hall’s bomb shelter. Carter’s fawning admiration for the selectman has changed. Although the special deputy doesn’t voice his defiance, he thinks it. In the wake of the disastrous raid on the methamphetamine lab and the firestorm it has caused, a definite rift has opened between the politician and his surrogate “son” and bodyguard.

Sam joins Barbie and his party. Dialogue between Barbie and his newfound girlfriend Julia Shumway reveals that the military intends to try a “pencil nuke” against the dome on Saturday.

While policing the area outside the dome near the Dinsmore farm, PFC Clint Ames hears someone knocking on the interior of the dome and relays the news to his superior, SGT Groh that “There’s somebody alive in there!” and calling for fans.

Sam tells the group of people atop Black Ridge that he’d fainted as he approached their location, but, upon awakening, he was attracted to the McCoy cabin by the “fans” and :lights” (1017) he saw there. While he was unconscious, Sam dreamed of Julia, naked, but “covered with. . . . issues of the Democrat,” as she lay “on the bandstand in the Commons,” crying (1017-1018). Colonel Cox, on the other side of the dome, is interrupted by the news that the Army has found “a survivor on the south side” (1018) of town.

Carter decides to kill Big Jim so that the bomb shelter’s oxygen supply will last him, the sole survivor, longer than it would if he had to continue to share it with the selectman. After replacing a spent canister of the propane that fuels their air supply, he upholsters his Beretta.

At the McCoy cabin, Ernie Calvert dies of a heart attack. Colonel Cox calls with bad news: the pencil nuke “melted down” before it could be deployed to Chester’s Mill. A replacement won’t be ready for deployment for three or four days. The Everett girls’ golden retriever, Audrey, also dies. These deaths are reminders that many others will also expire under the dome, as this section of the novel indicated in its opening paragraph.

Before killing Big Jim, Carter allows the politician a final prayer. When Big Jim starts to sob (or pretends to do so), he asks Carter to turn out the lights, claiming that it is unfitting for Carter to see him cry. Carter places the muzzle of his pistol against the selectman’s neck and extinguishes the light. “He knew it was a mistake the instant he did it,” the omniscient narrator remarks, “but by then it was too late” (1028). Big Jim stabs Carter, “pulling the knife upward s he rose” from his knees, “eviscerating the stupid boy who had thought to get the best of Big Jim Rennie” (1028). Carter falls to his knees and then onto his face, and Big Jim finishes Carter off with a bullet to the brain stem--delivered by Carter‘s own dropped Beretta--after imparting a final bit of advice: “Never give a good politician time to pray” (1029).

Ollie’s condition is much worse, despite the fan’s forcing of air through the dome, and SGT Groh believes him to be near death. He and PFC Ames keep a death vigil. Word comes that another child, on the north side of the dome, has died: Aidan Appleton.

At the McCoy cabin, Benny Drake and Joe McClatchey’s mother Claire seem feverishly hot, and Joe shares his concern with Barbie that they--and the rest of them as well--will die. There is no deliverance for them from outside the dome, he says. Julia, half-asleep, wishes that the extraterrestrial children who the party believes created and maintain the dome as a sadistic game, wishes the aliens would tire of their pastime or be called away by their parents to ear. The others raise some disturbing possibilities: maybe the aliens don’t eat and don’t have parents ands maybe “time is different for them” (1033), moving much quickly, so that, for them, the week the town has spent under the dome seems only seconds.

Atop Black Ridge, Thurston Marshall dies, and almost all the members of Barbie’s group are near death. Their condition is juxtaposed to an earlier catalogue of the everyday activities they and other residents of Chester’s Mill routinely performed on Saturday night, the normal and customary making the horrible all the more horrific and life, measured against death and dying, all the more precious. In an earlier scene, King’s omniscient narrator implies that Julia may be devising some sort of solution to their predicament, a resolution being pieced together, as it were, by her unconscious: “Julia was looking toward the box with its flashing purple light. Her face was thoughtful and a little dreamy” (1033). The narrator repeats this suggestion in this scene: “Julia . . . is once more looking in the direction of a box which, although less than fifty square inches in area and not even an inch thick, cannot be budged. Her eyes are distant, speculative” (1035). The author ends this scene with paraphrases of T. S. Eliot’s The Wasteland (“October is the cruelest month, mixing memory with desire” and “there are no lilacs in this dead land. No lilacs, no trees, no grass” (1035). It is obvious that King wants to associate his novel’s apocalyptic theme with the faithlessness of godless modern life that Eliot’s poem depicts. The question of whether he succeeds in doing so by making a couple of allusions to the poet’s work is a matter for each reader to decide for him- or herself, as is the question of whether King’s allusion to William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies has any more significance than its representing a rhetorical device.

In the next scene, Big Jim’s heart goes haywire again, just as the generator’s alarm sounds, indicating that the canister of propane that fuels it has become depleted. Struggling, the politician arises, stumbles over Carter’s corpse, imagining that his former aide’s sightless, staring eyes move. Shocked and frightened, Big Jim feels for a pulse in the special deputy’s throat, finding none. Reassured, he moves forward in the bomb shelter, toward the generator. Behind him, he hears a sound, imagining that it may be “the whisper of a hand, perhaps, slipping across the concrete floor” (1037). As Big Jim removes “one of the four remaining tanks” of propane from the “storage cubby, his heart went into arrhythmia again. It subsides, but Big Jim drops his flashlight (a second time) and the lens breaks, leaving him in total darkness. The generator refuses to restart, and Big Jim fights down the panic that threatens to rise inside him. His prayers seem to go unanswered. Disoriented in the darkness as he searches for batteries for the flashlight or a book of matches, Big Jim stumbles over Carter’s corpse and bangs his head. He crawls onto the couch and calms himself. As he experiences pain along his left arm, he fears he may be having a heart attack, and his sanity begins to slip away as he imagines that Carter is breathing--that several others are breathing as well: his other victims, Brenda Perkins, Lester Coggins, and his son Junior. The dead begin to speak to him, recalling the omniscient narrator’s declaration, earlier in the novel, that the dead coexist with the living but most living people cannot discern the presence of the dead. Terrified, Big Jim flees the bomb shelter. The stagnant air outside is too much for his failing heart, and he dies of a heart attack. This scene includes both humor and horror. One of the humorous portions is King’s omniscient narrator’s description of Big Jim, which compares the selectman to one of the used cars that he sells:

Big Jim jumped and cried out. His poor tortured heart was lurching, missing, skipping, then running to catch up with itself. He felt like an old car with a bad carburetor, the kind of rattletrap you might take in trade but would never sell, the kind that was good for nothing but the junk heap. . . (1036).On Sunday morning, Julia awakens Barbie with the news that Benny Drake has died. Julia says she wants to go to the dome generator, but Barbie reminds her that the air is so stale away from the fans that they can’t travel more than “fifty feet” (1043) and the dome generator is a half mile from them. However, Sam tells them that he knows a way they can take, offering to show them.