copyright 2008 by Gary L. Pullman

When one considers the variety of ways in which human beings are vulnerable, it’s a wonder that any of us manages to survive at all, to say nothing of the species itself. In horror fiction, such vulnerability is desirable, for it is the stuff of suspense, pathos, and dread. It behooves the writer of such fiction to keep handy, mentally or actually, a catalogue of vulnerabilities that he or she can call upon in times of dramatic need. This post represents a start of such a list, to which one may add any other vulnerabilities that may occur to him or her in the wee hours of the morning or when, within the deepening shadows of twilight, a mysterious sound is heard that sets the teeth upon edge and the hair upon end.

First, though, let’s consider what, precisely, we mean by the term “vulnerability.” What does it mean to say that someone is “vulnerable”? As is often the case, a simple list of synonyms and a bit of investigation as to the etymology of the resulting collection of terms sheds much light upon the matter. Let’s start with the synonyms:

Vulnerability: susceptibility, weakness (liability, flaw, fault, Achilles heel, failing, limitation, disadvantage, drawback), defenselessness (frailty, nakedness), helplessness, exposure.

This list suggests some examples from horror fiction and ideas for various situations that would put a victim--or even the protagonist--at risk. The shower scene in

Psycho, for example, involves nakedness, exposing Marion Crane to not only the ogling eyes of Norman Bates but also to the disapproving inspection of a voyeur--Norman’s alter ego, the misogynistic, murderous mom within. Similar shower scenes have since appeared in such horror movies as

Prowler,

Friday the 13th (a rare guy-in-the-shower scene),

Grudge, and others, as much because of the vulnerability of the victim--for obvious reasons, the victim is almost always a she--as for the gratuitous nudity that such scenes allow to voyeur--that is, the viewer.

The etymologies of these words also suggest profitable ways by which characters may become susceptible to horror villains' horrible villainy. “

Vulnerable” is derived from the late Latin term

vulnerabilis, which means “wounded.” A wounded character, naturally, is more likely to become monster food than one who is hale, hearty, and whole. “Weak” comes from an Old High German term that means “to bend,” and suggests that a victim could be such because of his or her emotional or moral as well as physical weakness, or ability to be “bent.” An emotionally crippled or morally twisted character makes a good potential villain. (Not all infirmities need to be literal ones; symbolism is always a welcome possibility in horror, as in other types of, fiction.) “Flaw” stems from the Old Norse word

flaga, meaning “stone slab” or “flake,” and was probably used, in the sense of a defect, as “fragment.” Characters who are physically, emotionally, mentally, morally, socially, spiritually, or otherwise “fragmented” or “flawed” had better look over their shoulders frequently, for, no doubt, The Doors’ “cold, grinding grizzly bear jaws” will be “hot on. . . [their] heels.” Or maybe its not a grizzly bear, but a bogeyman, who’s pursuing them. “

Frail” has an interesting etymology as well, suggesting, again, that vulnerabilities need not be limited to the physical aspects of a character’s constitution; more than bones may be broken, after all:

c.1340, "morally weak," from O.Fr. frele, from L. fragilis, "easily broken" (see fragility). Sense of "liable to break" is first recorded in Eng. 1382. The U.S. slang noun meaning "a woman" is attested from 1908.

Getting back to the list

per se--susceptibility suggests that victims may succumb to germs, as they do in sci fi and horror movies that involve extraterrestrial bacteria or viruses or exotic earthly germs that have unexpectedly hideous symptoms.

The Andromeda Strain, Cabin Fever, Dreamcatcher, The Invasion, Slither, and

Warning Sign are examples of novels or films (or, in some cases, both) in which the culprit that threatens individuals (and, in some cases, the planet’s population as a whole) is a germ of some sort. (The infection can come through infected animals, too, such as mad cows or rabid dogs, and some diseases--elephantiasis or rabies, for instance--are horrible in themselves--which can add to the horror of the story’s situation, specific and general.) However, as we will see, humans are susceptible to more than microbes’ attacks.

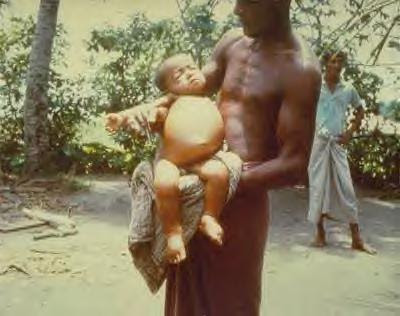

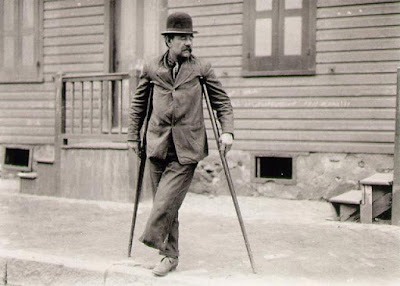

Weakness puts a character at risk, which is one reason that female characters and children, who are generally weaker than men, have traditionally been victims more often than male characters, although, lately, monsters are increasingly becoming equal-opportunity killers. Of course, there are other ways to be weak. A character can be mentally or emotionally vulnerable or unstable. Monsters are no respecters of infirmities, and will as readily slice and dice a character who is mentally ill as it will attack a character who is physically sick. Other forms or weakness may be derived from physical conditions that are not, in themselves, types of weakness or sickness but which are debilitating nonetheless, such as mental retardation, physical deformity, or being crippled or paralyzed. A bedfast or wheelchair-bound character is as enticing to a murderous monster as an

hors d’oeuvre is to a party crasher.

Frailty applies to some aged characters. The loss of flexibility in one’s joints, the presence of arthritis or rheumatism, the depletion of calcium in the bones, the atrophy of muscles, the attenuation of eyesight and hearing, a tendency toward forgetfulness, and the general depletion of one’s energy and physical strength combine to make some seniors ideal snacks for attacking monsters, so much so that it’s a wonder that more horror stories are not set in nursing homes or managed-care facilities.

Exposure to the elements, to scientific experiments, and to radioactive substances creates both monsters and victims in many sci fi and horror stories, including

Frankenstein, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Food of the Gods, The Island of Dr. Moreau, The Attack of the Fifty-foot Woman, The Incredible Shrinking Man, The Omega Man, Damnation Alley, and a host of others.

Other situations and conditions also render a character a potential victim, including sleep (

Nightmare on Elm Street) (it’s hard to fight or to take flight while one is asleep unless, perhaps, he or she is a dream warrior), being lost (

Wrong Turn), darkness (virtually every horror movie ever filmed, and a good many novels as well), isolation (

The Howling), sex (almost every slasher movie) (especially if the couple are underage and in a lonely spot, such as a forest) stupidity (a terminal state, if ever there was one), insanity (madness hampers one’s ability to think rationally or at all), envy (since the days of Cain and Abel, this emotion--and many others, for that matter--have brought characters to a bad, sometimes untimely, end), youth (or, more specifically, inexperience or naiveté), unwarranted trust (especially in the kindness of strangers), the pursuit of forbidden, usually occult knowledge (

Frankenstein and most stories involving ill-advised scientific experimentation or research or apprenticing oneself to a sorcerer or shaman of some kind), close-mindedness (skeptics, such as the protagonists of “The Red Room” and

1408 tend to come to harm), and a host of others--as we said, when one considers the variety of ways in which human beings are vulnerable, it’s a wonder that any of us manages to survive at all, to say nothing of the species itself.

What most of these states, conditions, and situations have in common is their interference with or prevention of the exercise either of the senses themselves or the body (the negation of physical abilities) or of the exercise of the mind (the negation of rational abilities). These circumstances, whether they originate in blindness, deafness, infirmity, paralysis, madness, naiveté, isolation, or otherwise, limit or eliminate a character’s ability to act and react, physically, mentally, or both, thereby inhibiting the fight-or-flight instinct and making victims of the vulnerable.

In most cases, something unpleasant--disease, sickness, dismemberment, torture, injury, disfigurement, and/or death--is apt to follow, individually or collectively. An exception occurs in

Buffy the Vampire Slayer, in which the stereotypically weak and helpless teenage girl turns out to be imbued with supernatural strength and fighting prowess and, instead of being slain by the monsters that stalk her, is

their slayer. In Hollywood, standing a cliché upon its head is enough, sometimes, to pass for creativity and to land one a series that lasts for seven years. (In fairness, the series had a lot more going for it than merely its iconoclasm.)

This catalogue is by no means complete--as we said, when one considers the variety of ways in which human beings are vulnerable, it’s a wonder that any of us manages to survive at all, to say nothing of the species itself--but it is a start. Writers, wannabe writers, and would-be writers alike are encouraged to update this list and to keep it handy. Victims are as much a necessity to horror fiction as the monster itself, and the monster is hungry; it’s

always hungry.

The Barbarian is typical of Frazetta’s depiction of the lone wolf who fends for himself, seeking vengeance or, more rarely, justice for others (usually an imperiled woman). Lean and mean, the barbarian stands, muscles bulging, his left hand resting upon the hilt of his unsheathed sword, which has penetrated the hill underfoot. His garb is slight, but exhibits his machismo. Pirate fashion, he wears earrings and sports a necklace that appears to have been fashioned of animal fangs or claws. His chest and abdominal muscles are as individually distinct as if they were sculpted from flesh instead of marble, and the wide, leather wristband and matching belt are both decorated with metal studs. An ornate scabbard hangs, empty, at his waist, from which dangles the lengths of a chain. On his right forearm, he wears a simple bracelet. He also wears boots with large cuffs. At first, because of the fiery yellow background against which he, an imposing, dark-haired, sun-darkened figure, stands, and the darkness of the mound upon which he is, as it were, rooted by his sword, it is not apparent that the hill is built not of soil alone but also of the body parts--an arm and a skull are visible--and a battleaxe--of enemies he has vanquished.

The fiery yellow sky behind him has an almost subliminal quality as well. After discerning the body parts in the hill, skulls, a castle upon a mountainside, vague suggestions of tree branches, and a bird--an eagle or maybe even a phoenix--emerge, as it were, from the wavering flames, representing, perhaps, the memories of the barbarian and the souls of the dead or both.

The Barbarian is typical of Frazetta’s depiction of the lone wolf who fends for himself, seeking vengeance or, more rarely, justice for others (usually an imperiled woman). Lean and mean, the barbarian stands, muscles bulging, his left hand resting upon the hilt of his unsheathed sword, which has penetrated the hill underfoot. His garb is slight, but exhibits his machismo. Pirate fashion, he wears earrings and sports a necklace that appears to have been fashioned of animal fangs or claws. His chest and abdominal muscles are as individually distinct as if they were sculpted from flesh instead of marble, and the wide, leather wristband and matching belt are both decorated with metal studs. An ornate scabbard hangs, empty, at his waist, from which dangles the lengths of a chain. On his right forearm, he wears a simple bracelet. He also wears boots with large cuffs. At first, because of the fiery yellow background against which he, an imposing, dark-haired, sun-darkened figure, stands, and the darkness of the mound upon which he is, as it were, rooted by his sword, it is not apparent that the hill is built not of soil alone but also of the body parts--an arm and a skull are visible--and a battleaxe--of enemies he has vanquished.

The fiery yellow sky behind him has an almost subliminal quality as well. After discerning the body parts in the hill, skulls, a castle upon a mountainside, vague suggestions of tree branches, and a bird--an eagle or maybe even a phoenix--emerge, as it were, from the wavering flames, representing, perhaps, the memories of the barbarian and the souls of the dead or both.