Tuesday, August 13, 2019

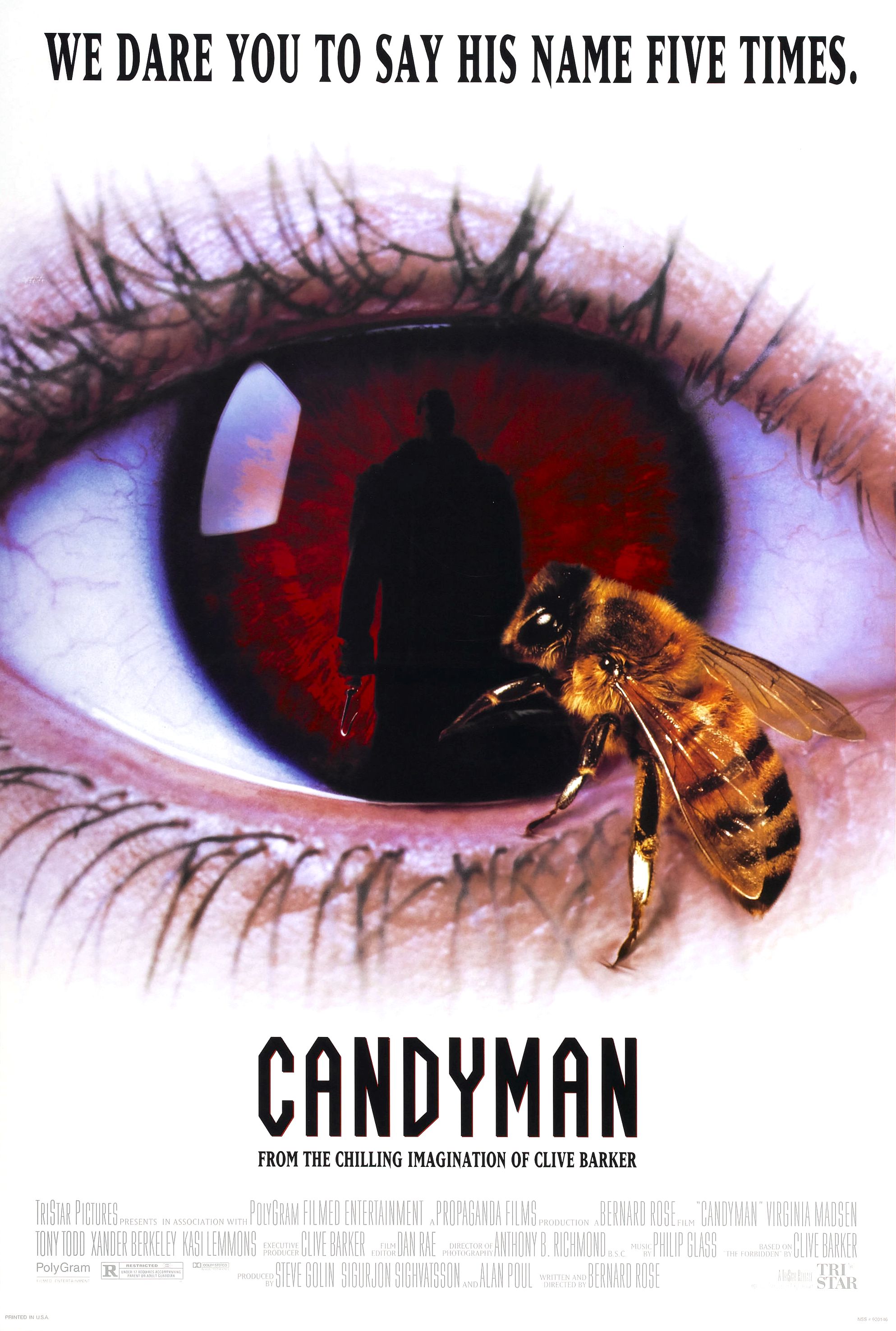

Telling Images: Horror Movie Poster Tropes

Monday, June 4, 2018

Making Every Word (or Image) Count

Saturday, May 26, 2018

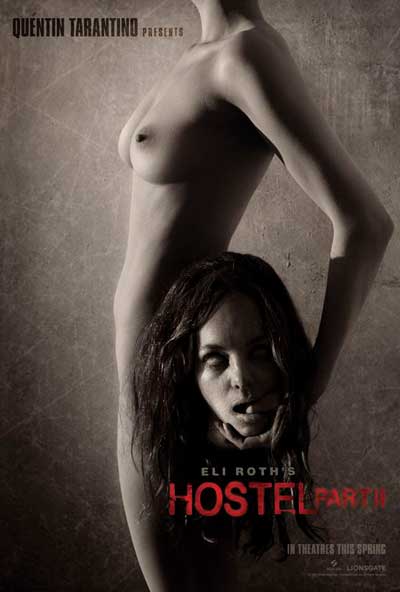

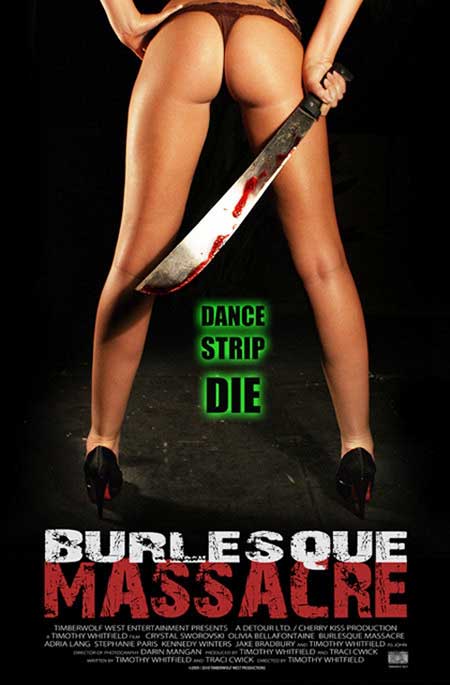

Nudity in Horror Films: More Than Just Gratuitous

Consider this full-page print ad.

The model, wearing a braand panty set and a pair of light-tan high-heeled shoes, sits, her posture erect, arms at her sides, right leg slightly forward, left leg slightly to the rear, gazing directly into the camera, as though she were making eye contact with the advertisement's viewer, whose eye probably starts with her face, which is framed by her dark, luxuriant hair, travels down and over her breasts, down her slender midriff, turns to trace her right thigh, and detours, at the bend of both knees, to continue down her left calf.

In the lower left corner of the photo, the product's brand name, in elegant white font against a cream-colored carpet, awaits the viewer's gaze: Fayreform, above smaller text in a different style of font that reads, as though it were a subtitle, the command, “Work your curves.”

Friday, September 2, 2011

Giger's Art: A Lesson for Horror Writers of the Biomechanical Age

When a face does appear, amid the wires and cords, plates and pipes, tubes and gears, hose connectors and clamps, presses and compressors, motors and switches, the eyes usually show only their whites. The irises are missing, signifying, perhaps, the agony or the death of the individual enmeshed in the machinery. Emphasis, in general, is given to the sex organs--breasts, vagina, buttocks, anus, penis, and testicles--the animal parts of men and (mostly) women. These organs are hooked into the machinery or, in some cases, have become one with the machines of which they are part, penises becoming pistons, vaginas sockets, breasts dome-shaped lids with nuts instead of nipples.

In Giger’s art, sadomasochism is taken to new heights--or lows. It has become passionless, it has become a matter of course, it is mechanical and perfunctory, operating under the same laws of physics as any other impersonal force in the universe. Penile pistons pump back and forth inside tubular vaginas without love, affection, or any kind of emotion, except, perhaps, mute horror, with the machine-like efficiency of a cog in a machine. Impaled, women seem to be all but unaware of their rape by the monstrous machines that ravish them, sometimes vaginally, sometimes orally, sometimes anally--sometimes in all these ways, simultaneously--to no purpose or end but, it seems, efficiency of motion, for, obviously, no machine is capable of inseminating a woman, nor is a woman who is partly--or even mostly--machine able to conceive or bear a child. The sex in Giger’s art is mechanical and purposeless, as absurd as the rest of the machinery in his factories of the damned. Sex, which, in times past, united couples, does not depend upon even the presence of a complete man or woman. All that is needed is the sex organs themselves and a face to register the misery and horror of dehumanized, mechanical existence in a determined and material world apart not only from God but from spirituality itself. This is the true horror of Giger’s horrific art.

- increased callousness toward women

- trivialization of rape as a criminal offense

- distorted perceptions about sexuality

- increased appetite for more deviant and bizarre types of pornography (escalation and addiction)

- devaluation of monogamy

- decreased satisfaction with a partner’s sexual performance, affection, and physical appearance

- doubts about the value of marriage

- decreased desire to have children

- viewing non-monogamous relationships as normal and natural behavior

Sunday, March 20, 2011

Not-So-Gratuitous Nudity

Nudity is popular in film for other reasons, too, though. Its promised display, for example, is a means of creating and maintaining suspense. Moviegoers of both sexes are curious as to what an actress looks like beneath her clothes. Men and women want to catch a glimpse of a famous female’s breasts, pubes, and buttocks, to see all (or almost all) there is to see, to observe the “bare truth” or the “naked truth” concerning the performer’s true outer beauty. To lay bare the body is, we believe, to lay bare the secrets of the soul. By suggesting that, eventually, this, that, or the other actress is likely to shed her clothes keeps moviegoers on the edges of their seats. When, where, and under what conditions will the screen siren reveal her charms, in all their gorgeous glory, are questions that sustain suspense.

Besides the creation and maintenance of suspense, nudity also reminds moviegoers of female characters’ femininity. Even clothed, women typically show themselves to be women in several hard-to-miss ways: long, styled hair; cosmetics; frilly attire; shaved underarms and legs; and the wearing of clothing and accessories that are designated by tradition and the dictates of fashion as belonging exclusively to women. Primary sexual characteristics (breasts, wider hips than men may claim, fuller buttocks than men may boast, and female genitalia) are indications as well, of course, and, usually, these characteristics are more or less noticeable in most women. However, when milady is nude, the unmistakable presence of primary sexual characteristics makes the artifices by which women proclaim their sex and gender unnecessary. One need not advertise herself as female and feminine through hairstyles, cosmetics, and clothing when, quite obviously, her body’s nakedness reveals her to be so.

Horror movies have recently become less sexist, offering moviegoers male as well as female victims and female and well as male predators, but the genre, nevertheless, remains largely chauvinistic and, one might argue, misogynistic. Women remain, far more often than men, the victims rather than the victimizers. One reason, besides sexism, for this preference for female over male victims is the relative physical weakness of women as compared to men. Because women typically have less physical strength than men do, they appear to be easier victims than men do. They also appear more vulnerable than men do. Weakness and vulnerability make them more likely to be victims than to be victimizers, for predators stalk the sick, the lame, and the lazy, or, in milady’s case, the weaker of the two sexes. Femaleness and femininity mark characters as relatively helpless and, therefore, as potential, even likely, victims. The nudity of female characters, in horror films, reminds audiences of the women’s identities as prospective casualties or fatalities.

Nudity in horror movies creates and maintains suspense, reminds moviegoers of female characters’ femininity and relative weakness and helplessness, but nudity also often leads to sex, and sex often leads to death or dismemberment. There is something of an unwritten law in the horror genre that taking one’s clothes off, even when it is not an act that is intended as a prelude to sex, is punishable by death; when nudity leads to sex, there is a virtual guarantee that it will end in pain, suffering, and the nudist’s demise. Even in the ultra permissive society in which we live, in which teen sex is rampant, as is teen pregnancy, abortion, and the birth of children to children, premarital sex, like adultery or other forms of sex outside the confines of holy matrimony, is considered taboo (by screenwriters in the horror genre, at least, if no one else), and it will surely be punished severely, with loss of limb, if not life. Nudity, as a precursor to sex, also identifies (often female) characters as likely victims. (The characters are more often female than male because most people believe that women look better in the nude than men do and because women seem more helpless, because they are typically physically weaker than men seem to be.)

We do a pretty good job of hiding our animal natures, but, despite our art, our culture, and our complex social structures, our philosophy and religion, and our humanity, we remain very much mammals who eat, drink, fornicate, sleep, and otherwise exhibit the animal within. We are not simply ghosts; we are ghosts in machines, and the machines we inhabit are made not of iron and steel but of flesh and blood. We are driven by fleshly as well as by psychological and social needs. We have appetites for food, for sex, for dominance, and for blood. The fact that, concealed beneath our shirts, blouses, trousers, and skirts, we have breasts and vaginas or penises and testicles and buttocks indicates that we are not merely human beings; we are also animals who breed and devour and hunt and kill. Nudity is a reminder of our animal natures, and female nudity is a reminder of the seldom-displayed, but always present, nudity of the male of the species. In seeing a nude woman, we understand that men, too, have “private parts” that disclose their animal nature, just as the undraped form of the female of the species reveals her own animality. Nakedness is a reminder, too, of our reproductive capability, a capability that we share with the so-called lower animals. Moreover, our nakedness reminds us that we, as much as lions and tigers and bears, oh my!, are (or can be) red in tooth and claw, that we are also potentially predators and prey, that we are, each and all, Drs. Jekylls and Mr. Hydes.

Under our clothes, we are flesh and blood, not the steely selves our aggressive personas sometimes tend to make others suppose we are. We can look daggers at another soul. We can set our jaws. We can give another person the cold shoulder. We can shake our fists and stamp our feet. We can stand tall. In short, we can use our bodies to intimidate others, but doing so while naked might be much more difficult, if not impossible, to do, because our fleshly selves, minus the armor of our suits and dresses, gives the lie, as it were, to the armor of costume and the arsenal of body language cues by which we seek to impose our wills upon others. It is hard to take someone in his or her birthday suit very seriously, no matter how he or she might glower or glare. Nudity renders us vulnerable. In horror movies, vulnerability of any kind is seldom a good thing and is apt, sooner or later, to get one killed. A nude character is a vulnerable character, and a vulnerable character is likely to become--well, a dead duck.

Nudity, we observe, is not necessarily gratuitous. In horror movies, as in other types of film, nakedness can, and frequently does, serve thematic purposes. (Typically, it also identifies probable victims and may characterize them as sexually promiscuous and, therefore, morally weak of perverse.)

In forthcoming posts, I will take up this matter again, exploring, more specifically, the contribution to the horror genre that on-screen nudity makes on a more-or-less regular basis.

Until then, for goodness’ sake, keep both the lights and your clothes on!

Monday, May 26, 2008

Frazetta: Work That Is Beautiful Even When Horrific

At the barbarian’s feet, her flesh of a hue similar to that of the fiery yellow sky, and looking as if she herself is emerging from the hill, a woman, nude but for the armbands that adorn her left biceps, rests her head against the barbarian’s left calf. Has she been rescued from the hands of the dead who lie beneath the victor’s feet? It seems that she is the only spoil of battle that he has seen fit to spare and, therefore, the only one that he regards as having any value. What is important in the barbarian’s world, Frazetta’s portrait of this pagan warrior suggests, is his physical and martial prowess, his memories of vanquished foes (or, it may be, his possession of their spirits), and women (albeit as little more than sex objects that may be acquired as possessions, or as part of the victors’ spoils of battle). Part of the appeal of Frazetta’s work is that it is often based upon these archetypal, if sexist, images of the masculine and the feminine, suggesting that men are loners who wage war with one another, with beasts, and with the occasional monster, exhibiting their strength, stamina, and fighting skills, and, to the notion that, to the victor, go the spoils, including ubiquitous half-naked damsels in distress. In other words, his depictions of men and women fit the idealized, if adolescent, ideas of the sexes that are typical of the readers of the types of magazines upon the covers of which Frazetta’s work was apt to appear. The rest of the appeal of the artist’s illustrations and paintings lies in the superb talent and the accomplished technique with which Frazetta draws and paints. Even when he depicts horror, the result is, in its own peculiar way, a thing of beauty.

Paranormal vs. Supernatural: What’s the Diff?

Sometimes, in demonstrating how to brainstorm about an essay topic, selecting horror movies, I ask students to name the titles of as many such movies as spring to mind (seldom a difficult feat for them, as the genre remains quite popular among young adults). Then, I ask them to identify the monster, or threat--the antagonist, to use the proper terminology--that appears in each of the films they have named. Again, this is usually a quick and easy task. Finally, I ask them to group the films’ adversaries into one of three possible categories: natural, paranormal, or supernatural. This is where the fun begins.

It’s a simple enough matter, usually, to identify the threats which fall under the “natural” label, especially after I supply my students with the scientific definition of “nature”: everything that exists as either matter or energy (which are, of course, the same thing, in different forms--in other words, the universe itself. The supernatural is anything which falls outside, or is beyond, the universe: God, angels, demons, and the like, if they exist. Mad scientists, mutant cannibals (and just plain cannibals), serial killers, and such are examples of natural threats. So far, so simple.

What about borderline creatures, though? Are vampires, werewolves, and zombies, for example, natural or supernatural? And what about Freddy Krueger? In fact, what does the word “paranormal” mean, anyway? If the universe is nature and anything outside or beyond the universe is supernatural, where does the paranormal fit into the scheme of things?

According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word “paranormal,” formed of the prefix “para,” meaning alongside, and “normal,” meaning “conforming to common standards, usual,” was coined in 1920. The American Heritage Dictionary defines “paranormal” to mean “beyond the range of normal experience or scientific explanation.” In other words, the paranormal is not supernatural--it is not outside or beyond the universe; it is natural, but, at the present, at least, inexplicable, which is to say that science cannot yet explain its nature. The same dictionary offers, as examples of paranormal phenomena, telepathy and “a medium’s paranormal powers.”

Wikipedia offers a few other examples of such phenomena or of paranormal sciences, including the percentages of the American population which, according to a Gallup poll, believes in each phenomenon, shown here in parentheses: psychic or spiritual healing (54), extrasensory perception (ESP) (50), ghosts (42), demons (41), extraterrestrials (33), clairvoyance and prophecy (32), communication with the dead (28), astrology (28), witchcraft (26), reincarnation (25), and channeling (15); 36 percent believe in telepathy.

As can be seen from this list, which includes demons, ghosts, and witches along with psychics and extraterrestrials, there is a confusion as to which phenomena and which individuals belong to the paranormal and which belong to the supernatural categories. This confusion, I believe, results from the scientism of our age, which makes it fashionable for people who fancy themselves intelligent and educated to dismiss whatever cannot be explained scientifically or, if such phenomena cannot be entirely rejected, to classify them as as-yet inexplicable natural phenomena. That way, the existence of a supernatural realm need not be admitted or even entertained. Scientists tend to be materialists, believing that the real consists only of the twofold unity of matter and energy, not dualists who believe that there is both the material (matter and energy) and the spiritual, or supernatural. If so, everything that was once regarded as having been supernatural will be regarded (if it cannot be dismissed) as paranormal and, maybe, if and when it is explained by science, as natural. Indeed, Sigmund Freud sought to explain even God as but a natural--and in Freud’s opinion, an obsolete--phenomenon.

Meanwhile, among skeptics, there is an ongoing campaign to eliminate the paranormal by explaining them as products of ignorance, misunderstanding, or deceit. Ridicule is also a tactic that skeptics sometimes employ in this campaign. For example, The Skeptics’ Dictionary contends that the perception of some “events” as being of a paranormal nature may be attributed to “ignorance or magical thinking.” The dictionary is equally suspicious of each individual phenomenon or “paranormal science” as well. Concerning psychics’ alleged ability to discern future events, for example, The Skeptic’s Dictionary quotes Jay Leno (“How come you never see a headline like 'Psychic Wins Lottery'?”), following with a number of similar observations:

Psychics don't rely on psychics to warn them of impending disasters. Psychics don't predict their own deaths or diseases. They go to the dentist like the rest of us. They're as surprised and disturbed as the rest of us when they have to call a plumber or an electrician to fix some defect at home. Their planes are delayed without their being able to anticipate the delays. If they want to know something about Abraham Lincoln, they go to the library; they don't try to talk to Abe's spirit. In short, psychics live by the known laws of nature except when they are playing the psychic game with people.In An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural, James Randi, a magician who exercises a skeptical attitude toward all things alleged to be paranormal or supernatural, takes issue with the notion of such phenomena as well, often employing the same arguments and rhetorical strategies as The Skeptic’s Dictionary.

In short, the difference between the paranormal and the supernatural lies in whether one is a materialist, believing in only the existence of matter and energy, or a dualist, believing in the existence of both matter and energy and spirit. If one maintains a belief in the reality of the spiritual, he or she will classify such entities as angels, demons, ghosts, gods, vampires, and other threats of a spiritual nature as supernatural, rather than paranormal, phenomena. He or she may also include witches (because, although they are human, they are empowered by the devil, who is himself a supernatural entity) and other natural threats that are energized, so to speak, by a power that transcends nature and is, as such, outside or beyond the universe. Otherwise, one is likely to reject the supernatural as a category altogether, identifying every inexplicable phenomenon as paranormal, whether it is dark matter or a teenage werewolf. Indeed, some scientists dedicate at least part of their time to debunking allegedly paranormal phenomena, explaining what natural conditions or processes may explain them, as the author of The Serpent and the Rainbow explains the creation of zombies by voodoo priests.

Based upon my recent reading of Tzvetan Todorov's The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to the Fantastic, I add the following addendum to this essay.

According to Todorov:

The fantastic. . . lasts only as long as a certain hesitation [in deciding] whether or not what they [the reader and the protagonist] perceive derives from "reality" as it exists in the common opinion. . . . If he [the reader] decides that the laws of reality remain intact and permit an explanation of the phenomena described, we can say that the work belongs to the another genre [than the fantastic]: the uncanny. If, on the contrary, he decides that new laws of nature must be entertained to account for the phenomena, we enter the genre of the marvelous (The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre, 41).Todorov further differentiates these two categories by characterizing the uncanny as “the supernatural explained” and the marvelous as “the supernatural accepted” (41-42).

Interestingly, the prejudice against even the possibility of the supernatural’s existence which is implicit in the designation of natural versus paranormal phenomena, which excludes any consideration of the supernatural, suggests that there are no marvelous phenomena; instead, there can be only the uncanny. Consequently, for those who subscribe to this view, the fantastic itself no longer exists in this scheme, for the fantastic depends, as Todorov points out, upon the tension of indecision concerning to which category an incident belongs, the natural or the supernatural. The paranormal is understood, by those who posit it, in lieu of the supernatural, as the natural as yet unexplained.

And now, back to a fate worse than death: grading students’ papers.

My Cup of Blood

Anyway, this is what I happen to like in horror fiction:

Small-town settings in which I get to know the townspeople, both the good, the bad, and the ugly. For this reason alone, I’m a sucker for most of Stephen King’s novels. Most of them, from 'Salem's Lot to Under the Dome, are set in small towns that are peopled by the good, the bad, and the ugly. Part of the appeal here, granted, is the sense of community that such settings entail.

Isolated settings, such as caves, desert wastelands, islands, mountaintops, space, swamps, where characters are cut off from civilization and culture and must survive and thrive or die on their own, without assistance, by their wits and other personal resources. Many are the examples of such novels and screenplays, but Alien, The Shining, The Descent, Desperation, and The Island of Dr. Moreau, are some of the ones that come readily to mind.

Total institutions as settings. Camps, hospitals, military installations, nursing homes, prisons, resorts, spaceships, and other worlds unto themselves are examples of such settings, and Sleepaway Camp, Coma, The Green Mile, and Aliens are some of the novels or films that take place in such settings.

Anecdotal scenes--in other words, short scenes that showcase a character--usually, an unusual, even eccentric, character. Both Dean Koontz and the dynamic duo, Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, excel at this, so I keep reading their series (although Koontz’s canine companions frequently--indeed, almost always--annoy, as does his relentless optimism).

Atmosphere, mood, and tone. Here, King is king, but so is Bentley Little. In the use of description to terrorize and horrify, both are masters of the craft.

Innovation. Bram Stoker demonstrates it, especially in his short story “Dracula’s Guest,” as does H. P. Lovecraft, Edgar Allan Poe, Shirley Jackson, and a host of other, mostly classical, horror novelists and short story writers. For an example, check out my post on Stoker’s story, which is a real stoker, to be sure. Stephen King shows innovation, too, in ‘Salem’s Lot, The Shining, It, and other novels. One might even argue that Dean Koontz’s something-for-everyone, cross-genre writing is innovative; he seems to have been one of the first, if not the first, to pen such tales.

Technique. Check out Frank Peretti’s use of maps and his allusions to the senses in Monster; my post on this very topic is worth a look, if I do say so myself, which, of course, I do. Opening chapters that accomplish a multitude of narrative purposes (not usually all at once, but successively) are attractive, too, and Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child are as good as anyone, and better than many, at this art.

A connective universe--a mythos, if you will, such as both H. P. Lovecraft and Stephen King, and, to a lesser extent, Dean Koontz, Bentley Little, and even Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child have created through the use of recurring settings, characters, themes, and other elements of fiction.

A lack of pretentiousness. Dean Koontz has it, as do Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, Bentley Little, and (to some extent, although he has become condescending and self-indulgent of late, Stephen King); unfortunately, both Dan Simmons and Robert McCammon have become too self-important in their later works, Simmons almost to the point of becoming unreadable. Come on, people, you’re writing about monsters--you should be humble.

Longevity. Writers who have been around for a while usually get better, Stephen King, Dan Simmons, and Robert McCammon excepted.