Characterization operates by means of depicting emotion. Literary characters are, in fact, embodiments of emotion. Some emotions may be negative, either in the sense that they are unpleasant or in the sense that they cause problems, personal, social, or otherwise. Emotions can also be positive because they are pleasant or because they alleviate or resolve problems, personal, social, or otherwise.

Characters’ responses to incidents--that is, their feelings concerning events--motivate their actions. In other words, characters are often reactive: they respond to internal or external stimuli. Internal stimuli are their own attitudes, beliefs, desires, fantasies, hopes, thoughts, and, of course, emotions, such as fear, love, and self-respect. External stimuli are persons, places, things, qualities, and ideas that elicit characters’ passions, and can include threats, money, beauty, and death.

The overall, consistent pattern which underlies and is discerned in an individual’s behavior over an extended period of time suggests his or her basic personality traits and causes him or her to be regarded as just, wise, kind, ruthless, arrogant, vain, or whatever. However, many lesser, secondary traits also comprise most fictional people at any time of his or her literary life.

Hamlet is driven by his sense of duty to avenge his murdered father, but he is also hesitant, wanting to make sure that he acts justly in killing his father’s true killer--if, indeed, his father was killed, as the spirit who alleges to be the ghost of his father contends the late king was. These traits are the primary ones that motivate Hamlet, both to act and to refrain from acting. Therefore, he can be said to be a dutiful and just, but hesitant, character. In short, we might regard him as being a man of valor.

His antagonist, who is also his uncle and his step-father, King Claudius, is shown to be cold, calculating, and unrepentant, and he is driven by lust, both for power and for sex, having married Hamlet’s mother, Gertrude, shortly after Hamlet’s father died. Therefore, Hamlet can be read as a dramatization of a conflict between these two sets of emotions: Hamlet’s dutifulness, justice, and hesitation collide with Claudius’ coldness, calculation, unwillingness to repent, and lust for power and sex.

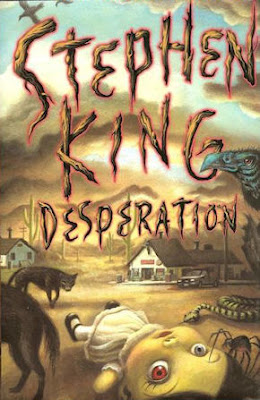

Horror fiction is primarily about fear, but its characters are motivated by other emotions as well. Beowulf’s hero wants to prove his mettle as a warrior. Although The Exorcist’s Father Damian Karras has begin to doubt and, perhaps, to lose his faith, he remains a man of God who loves humanity, as it is represented in the possessed soul of young Regan MacNeil, enough to risk his own life in an attempt to exorcise the devil’s victim. Many of Stephen King’s characters are motivated by their need to bond and by their need to belong to a community, or by brotherly love, one might say.

Not only the protagonists of horror fiction are motivated by their emotions; their antagonists are as well. In Beowulf, the monstrous outcast, Grendel, attacks the Danes because he envies their camaraderie. In The Exorcist, the devil possesses Regan in an attempt to get Father Karras to renounce his faith and thus be damned. Many of King’s villains (‘Salem’s Lot’s Barlow, Andre Linoge in Storm of the Century, and the protean monster of It, for example) prey upon the weaknesses of small communities and their residents, motivated by their narcissistic desire to perpetuate themselves. The emotional conflicts in Beowulf, The Exorcist, and ‘Salem’s Lot can be represented this way:

Valor vs. EnvyBy motivating your characters to act according to their passions, you will make your fiction seem more realistic, and you will show what’s at stake, on a personal level, as it were, in the struggle between the story’s protagonist and antagonist. The nature of the struggle, in turn, may suggest your stories’ themes. For example, The Exorcist suggests that love casts out condemnation, just as Beowulf implies that valor vanquishes envy and King's novels indicate that brotherly love is more important than narcissistic self-perpetuation.

Love vs. Condemnation

Brotherly Love vs. Narcissistic self-perpetuation