Copyright 2021 by Gary L. Pullman

As bestselling author James Patterson points out, thrillers, which span the whole spectrum of genres, are characterized by “the intensity of emotions they create, particularly those of apprehension and exhilaration, of excitement and breathlessness, all designed to generate that all-important thrill” (Thriller).

To generate thrills, thriller authors pull out all the stops, employing isolated settings, traps, disguises, cover-ups, red herrings, plot twists, unreliable narrators, cliffhangers, situational irony, and dramatic irony. Many thrillers also begin in media res, in the middle of things, so there is little or no context to explain mysterious events until, in due time, they are explained through flashbacks, dialogue, exposition, or other means.

By taking an Aristotelian approach to analyzing thrillers, we can develop a long list of incidents common to thrillers. (By “Aristotelian approach,” I mean studying how established writers of thrillers keep their readers on the edges of their seats.) In doing so, we want to universalize our incidents so that they can apply to any character in any thriller, existing or yet to come. To do so, we dispense with names, and we tend to repeat phrases. The idea is to isolate plot elements (incidents) that can

occur in any thriller and that can be used in several ways (e. g., as inciting moments, turning points, moments of final suspense);

be used individually or in groups, sequentially (as per the list) or otherwise;

be mixed and matched in various combinations.

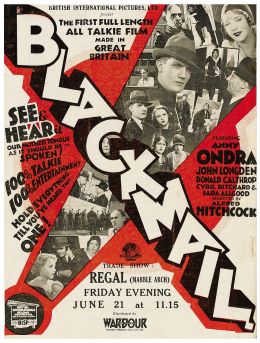

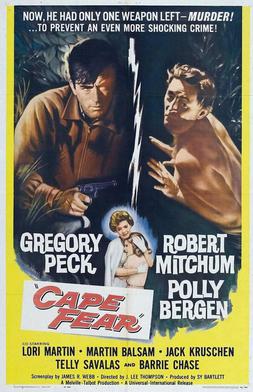

By way of example, I have assembled a partial list of one that, ideally, would be long enough to fill a book of many pages. I have listed the incidents as they occur in the plots of the films from which they are taken (but, remember, they can be assembled in any fashion, with any number of them being used, and they can be used for several narrative purposes). In addition, at the beginning of each incident, in bold font, I have identified the category that each incident seems to fit, by way of its function. This would be only the beginning of a list that could (and should) be expanded to include many incidents from movies or novels of the same category, or subgenre, of story. As my subgenre, I have used examples of psychological thrillers: Alfred Hitchcock’s Blackmail (1929) and J. Lee Thompson’s Cape Fear (1962).

From Blackmail

Vulnerability: A woman is left alone.

Poor judgment; self-endangerment: A woman accompanies a stranger to another location.

False sense of security: A stranger puts (or tries to put) a woman at ease.

Incriminating evidence: Unknowingly, a woman provides evidence that later incriminates (or could incriminate) her.

Attempted sexual assault: A stranger attempts to rape a woman.

Assistance unavailable: A woman’s cries for help go unanswered.

Self-defense: A woman fights for her life.

Fatal encounter: A woman kills her attacker.

Shock: In a daze, a traumatized woman wanders the streets all night.

Discovery of crime: A stranger’s body is found.

Initiation of investigation: A detective is assigned to a murder investigation.

Discovery of incriminating evidence: A detective finds incriminating evidence at a crime scene.

Recognition: A detective recognizes a dead person.

Removal of incriminating evidence: A detective removes incriminating evidence from a crime scene.

Interrogation of suspect: A detective interrogates a suspect.

Sympathetic character: A suspect is too distraught to answer a detective’s questions.

Accommodation: A detective speaks to a suspect in private.

Witness’s observation: An eyewitness sees a woman accompany a man to his quarters.

Recovery of incriminating evidence: An eyewitness recovers incriminating evidence from a crime scene.

Linking of incriminating evidence to suspect: An eyewitness links recovers incriminating evidence he has recovered from a crime scene based on complementary or matching evidence in a detective’s possession.

Blackmail: An eyewitness blackmails a detective and a suspect.

Criminal record: An eyewitness is revealed to have a criminal record and is wanted for questioning concerning a criminal investigation.

Back-up: A detective sends for police officers.

Flight: A suspect flees from police.

Accidental death; removal of a threat: Fleeing from police, a suspect falls to his death.

Acceptance of resolution: Police assume that a suspect who fell to his death while fleeing from police is the criminal they sought.

Intention to confess: A suspect goes to the police to confess to having committed a crime.

Fortuitous coincidence: A police inspector receives a telephone call and instructs a detective to assist a woman who has come to the station or precinct to confess to a crime.

Confession with mitigating factor: A woman confesses to having committed a crime but offers a just reason for having done so.

Apparent escape: A detective and a suspect leave a police station together.

Possibility of prosecution: A police officer arrives at the station or precinct with evidence in hand that could incriminate a suspect.

(To see the details of these plot incidents as Hitchcock uses them in Blackmail, read a summary of the movie’s plot.)

From Cape Fear

Release: A convicted criminal is paroled.

Return: A parolee tracks down the person he blames for his conviction.

Threat: The parolee threatens the family of the person whom he blames for his conviction.

Stalking: The parolee stalks the family of the person whom he blames for his conviction.

Terrorism: The parolee kills the dog that belongs to the family of the person whom he blames for his conviction.

Protection: A man threatened by a parolee hires a private detective.

Crime: A parolee rapes a woman.

Intimidation: A rape victim refuses to testify against the man who raped her.

Intervention: The person whom a parolee blames for his conviction hires three men to beat the parolee to force him to leave town.

Failed intervention: The parolee gets the better of the three men hired to beat him.

Punishment of victim: A parolee’s intended victim is disbarred as a result of having hired three men to beat the parolee so he would leave town.

Refuge: A parolee’s intended victim takes his family to a houseboat to protect them from a vengeful parolee.

Lying in wait; protection: A local lawman and a parolee’s intended victim lie in wait to arrest a parolee who plans to attach the victim’s family.

Attrition: A parolee kills a local lawman lying in wait to arrest him.

Escape: A parolee eludes his intended victim.

Isolation: A parolee isolates the family of his intended victim.

Strategic attack (feint): A parolee attacks the wife of his intended victim.

Rescue: A parolee’s intended victim rescues his wife from the parole.

Attack: A parolee attacks his intended victim’s daughter.

Rescue: An intended victim rescues his daughter from a vengeful parolee.

Struggle: An intended victim fights a vengeful parolee.

Neutralization: An intended victim shoots a vengeful parolee, wounding and disabling him.

Plea: A vengeful parolee asks his intended victim to kill him.

Ironic vengeance (poetic justice): A parolee’s intended victim refrains from killing a vengeful parolee, preferring that he be returned to prison for life instead.

Resolution: A parolee’s intended victim and his family, accompanied by police, return home.

(To see the details of these plot incidents as Thompson uses them in Cape Fear, read a summary of the movie’s plot.)

Concluding Thoughts

These incidents could be even further generalized to attain true universality. For example, “The parolee kills the dog that belongs to the family of the person whom he blames for his conviction” could be rewritten as “The parolee intimidates the family of the person whom he blames for his conviction” or “The parolee terrorizes the family of the person whom he blames for his conviction.” The degree to which any incident is generalized depends on your own purposes as a writer creating such a list. The list, of course, can be either further generalized or made more specific, as circumstances warrant. For this reason, it may be desirable to keep a “master list” and make a copy of it to generalize more or less, as circumstances warrant.

An extensive list of thriller incidents allows you to pick and choose which incident on the list might best be used for a specific purpose, such as an inciting moment, a turning point, a moment of final suspense, a flashback, a flash-forward, a cliffhanger, exposition, etc. For example, almost any of the incidents on this list could serve the function of the inciting moment, initiating the rest of the story:

Of course, the story will change accordingly, since the incidents of a plot must be connected through an ongoing series of causes and effects. Furthermore, you will develop the incidents in your own way, so they will not be the same, in detail, as those of Hitchcock, Thompson, or any other director or writer. As Heraclitus observed, long ago, it is impossible to step into the same river twice; the water, the silt, the fish, the current, the temperature are all different each time.