Saturday, June 20, 2020

The Lamb and The Tyger by William Blake: Analysis and Commentary

Tuesday, July 24, 2018

All's Well That Ends Well

Sunday, October 10, 2010

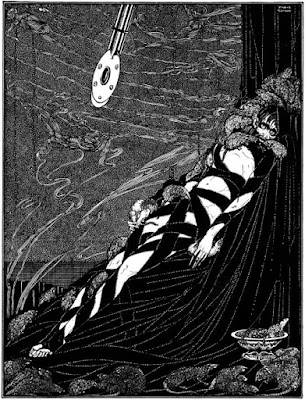

Edgar Allan Poe: An Obituary and a Eulogy

Even the author’s reputation as a man of letters was questionable, Griswold implied: “Literary art has lost one of its most brilliant but erratic stars.” Griswold, assuming the name of “Ludwig,” characterizes Poe as a dissolute alcoholic who lived a penurious and friendless existence at the expense, as often as not, of his benefactors. He was, “Ludwig” all but insists, little more than a freeloader:

His wants were supplied by the liberality of a few individuals. We remember that Col. Webb collected in a few moments fifty or sixty dollars for him at the Union Club; Mr. Lewis, of Brooklyn, sent a similar sum from one of the Courts, in which he was engaged when he saw the statement of the poet’s poverty; and others illustrated in the same manner the effect of such an appeal to the popular heart.Poe came to the attention of the literati as a result of an accident, Griswold claims. He had entered a literary contest, and his story won not because it had any merit, but because it was the first among the many entries that showed any legibility, and the judges, in selecting it as the winner, might be done as quickly as possible with their responsibility:

Such matters are usually disposed of in a very off hand way: Committees to award literary prizes drink to the payer’s health, in good wines, over the unexamined MSS, which they submit to the discretion of publishers, with permission to use their names in such a way as to promote the publisher’s advantage[[.]] So it would have been in this case, but that one of the Committee, taking up a little book in such exquisite calligraphy as to seem like one of the finest issues of the press of Putnam, was tempted to read several pages, and being interested, he summoned the attention of the company to the half-dozen compositions in the volume. It was unanimously decided that the prizes should be paid to the first of geniuses who had written legibly. Not another MS. was unfolded. Immediately the ‘confidential envelop’ was opened, and the successful competitor was found to bear the scarcely known name of Poe.Had it not been for the intervention of another benefactor, “the accomplished author” John P. Kennedy, who’d written Horseshoe Robinson, it seems unlikely, Griswold would have his readers believe, that Poe would ever have been likely to have earned himself the position of editor of The Southern Literary Messenger at even the “small salary” that Poe was paid:

The next day the publisher called to see Mr. Kennedy, and gave him an account of the author that excited his curiosity and sympathy, and caused him to request that he should be brought to his office. Accordingly he was introduced: the prize money had not yet been paid, and he was in the costume in which he had answered the advertisement of his good fortune. Thin, and pale even to ghastliness, his whole appearance indicated sickness and the utmost destitution. A tattered frock-coat concealed the absence of a shirt, and the ruins of boots disclosed more than the want of stockings[[.]] But the eyes of the young man were luminous with intelligence and feeling, and his voice, and conversation, and manners, all won upon the lawyer’s regard. Poe told his history, and his ambition, and it was determined that he should not want means for a suitable appearance in society, nor opportunity for a just display of his abilities in literature. Mr. Kennedy accompanied him to a clothing store, and purchased for him a respectable suit, with changes of linen, and sent him to a bath, from which he returned with the suddenly regained bearing of a gentleman.In keeping with his image of Poe as a ne’er-do-well who lived off others, Griswold also characterizes Poe as something of a vagabond, mentioning his moves from Richmond to Philadelphia; from Philadelphia to New York; from New York back again to Richmond; and, finally, as it seemed, judging by his death in Baltimore, back again to New York.

The late Mr. Thomas W. White had then recently established The Southern Literary Messenger, at Richmond, and upon the warm recommendation of Mr. Kennedy, Poe was engaged, at a small salary — we believe of $500 a year — to be its editor.

In the years following the death of his “poor” wife, whom Poe had married “hurriedly” and “with characteristic recklessness of consequences,” at a time when he was as penniless as she, the author was able to make a meager living on the basis of “an income from his literary labors sufficient for his support.” However, Griswold suggests, Poe continued to keep an eye out for the chance to freeload, for, as “Ludwig,” or Griswold, points out, Poe “was understood by some of his correspondents” to be planning “to be married, most advantageously, to a lady of that city: a widow, to whom he had been previously engaged while a student in the University.”

As a man, Poe didn’t amount to much, either, Griswold’s death notice suggests: “He was at all times a dreamer,” who walked about not with his head so much in the clouds as “in heaven or hell,” communing with imaginary beings, the “creatures and the accidents of his brain”:

He walked the streets, in madness or melancholy, with lips moving in indistinct curses, or with eyes upturned in passionate prayers, (never for himself, for he felt, or professed to feel, that he was already damned), but for their happiness who at the moment were objects of his idolatry — or, with his glances introverted to a heart gnawed with anguish, and with a face shrouded in gloom, he would brave the wildest storms; and all night, with drenched garments and arms wildly beating the winds and rains, he would speak as if to spirits that at such times only could be evoked by him from the Aidenn close by whose portals his disturbed soul sought to forget the ills to which his constitution subjugated him — close by that Aidenn where were those he loved — the Aidenn which he might never see, but in fitful glimpses, as its gates opened to receive the less fiery and more happy natures whose destiny to sin did not involve the doom of death.The true man is mirrored by his works, Griswold says, and Poe’s works are dark and dreary, indeed:

He seemed, except when some fitful pursuit subjected his will and engrossed his faculties, always to bear the memory of some controlling sorrow. The remarkable poem of The Raven was probably much more nearly than has been supposed, even by those who were very intimate with him, a reflexion and an echo of his own history.

Every genuine author in a greater or less degree leaves in his works, whatever their design, traces of his personal character: elements of his immortal being, in which the individual survives the person. While we read the pages of the Fall of the House of Usher, or of Mesmeric Revelations, we see in the solemn and stately gloom which invests one, and in the subtle metaphysical analysis of both, indications of the idiosyncrasies, — of what was most remarkable and peculiar — in the author’s intellectual nature. But we see here only the better phases of this nature, only the symbols of his juster action, for his harsh experience had deprived him of all faith in man or woman. He had made up his mind upon the numberless complexities of the social world, and the whole system with him was an imposture. This conviction gave a direction to his shrewd and naturally unamiable character. Still, though he regarded society as composed altogether of villains, the sharpness of his intellect was not of that kind which enabled him to cope with villainy, while it continually caused him by overshots to fail of the success of honesty.A friend of Poe’s, George R. Graham, answers Griswold’s character assassination-disguised-as-an-obituary with a eulogy in which he praises Poe (“The Late Edgar Allan Poe,” Graham’s Magazine, March 1850, 36: 224-226). Adopting the device of writing his eulogy to Willis, a mutual friend of Poe and himself, Graham begins by taking unto himself the task of writing a “defence [sic] of his character” as it was “set down by Dr. Rufus W. Griswold.”

“I knew Mr. Poe well — far better than Mr. Griswold,” Graham writes, and he immediately describes Griswold’s portrait of Poe an “exceedingly ill-timed and unappreciative estimate of the character of our lost friend,” which is both “unfair and untrue.” Graham believes that Griswold demonizes Poe out of spite, or “spleen.” Griswold’s obituary is, in fact, Graham argues, an attempt to avenge himself and his friends upon Poe for Poe’s honest criticisms of their literary works:

Mr. Griswold does not feel the worth of the man he has undervalued; — he had no sympathies in common with him, and has allowed old prejudices and old enmities to steal, insensibly perhaps, into the coloring of his picture. They were for years totally uncongenial, if not enemies, and during that period Mr. Poe, in a scathing lecture upon [[“]]The Poets of America,[[”]] gave Mr. Griswold some raps over the knuckles of force sufficient to be remembered. He had, too, in the exercise of his functions as critic, put to death, summarily, the literary reputation of some of Mr. Griswold’s best friends; and their ghosts cried in vain for him to avenge them during Poe’s life-time.What Griswold and his friends were incapable of achieving during Poe’s life, Griswold sought to gain after his death, by cowardly accusing Poe of charges against which Poe could not now defend himself. However, Graham suggests, even if Griswold had not had an axe to grind, Griswold would have not been “competent. . . to act as his judge — to dissect that subtle and singularly fine intellect — to probe the motives and weigh the actions of that proud heart” because not only did Griswold not “feel the worth of the man he has undervalued” but he also could not measure Poe’s worth, since Poe’s “whole nature — that distinctive presence of the departed which now stands impalpable, yet in strong outline before me, as I knew him and felt him to be — eludes the rude grasp of a mind so warped and uncongenial as Mr. Griswold’s.”

As a man, Griswold found Poe to have had close friends and to have been “always the same polished gentleman — the quiet, unobtrusive, thoughtful scholar — the devoted husband — frugal in his personal expenses — punctual and unwearied in his industry — and the soul of honor, in all his transactions. This, of course, was in his better days, and by them we judge the man. But even after his habits had changed, there was no literary man to whom I would more readily advance money for labor to be done.” As for his being a ne’er-do-well or a freeloader, Graham says, Poe was of such a rarified genius that his writings found only a small audience, (and literature is an enterprise that seldom pays well, in any case). He drank because he made little at doing what he loved so well:

The very natural question — “Why did he not work and thrive?” is easily answered. It will not be asked by the many who knew the precarious tenure by which literary men hold a mere living in this country. The avenues through which they can profitably reach the country are few, and crowded with aspirants for bread as well as fame. The unfortunate tendency to cheapen every literary work to the lowest point of beggarly flimsiness in price and profit, prevents even the well-disposed from extending any thing like an adequate support to even a part of the great throng which genius, talent, education, and even misfortune, force into the struggle. The character of Poe’s mind was of such an order, as not to be very widely in demand. The class of educated mind which he could readily and profitably address, was small — the channels through which he could do so at all, were few — and publishers all, or nearly all, contented with such pens as were already engaged, hesitated to incur the expense of his to an extent which would sufficiently remunerate him; hence, when he was fairly at sea, connected permanently with no publication, he suffered all the horrors of prospective destitution, with scarcely the ability of providing for immediate necessities; and at such moments, alas! the tempter often came, and, as you have truly said, “one glass” of wine made him a madman. Let the moralist who stands upon tufted carpet, and surveys his smoking board, the fruits of his individual toil or mercantile adventure, pause before he lets the anathema, trembling upon his lips, fall upon a man like Poe! who, wandering from publisher to publisher, with his fine, print-like manuscript, scrupulously clean and neatly rolled, finds no market for his brain — with despair at heart, misery ahead for himself and his loved ones, and gaunt famine dogging at his heels, thus sinks by the wayside, before the demon that watches his steps and whispers OBLIVION.The solution might have been to sell out and write the hack work that a general audience more interested in entertainment than art seemed to crave, but Poe was too much a man of honor to do so, Graham declares: “Could he have stepped down and chronicled small beer, made himself the shifting toady of the hour, and with bow and cringe, hung upon the steps of greatness, sounding the glory of third-rate ability with a penny trumpet, he would have been feted alive, and perhaps, been praised when dead. But no! his views of the duty of the critic were stern, and he felt that in praising an unworthy writer, he committed dishonor.”

Rather than the idle, half-mad dreamer that Griswold had made Poe out to be, Poe was a man of genius, Graham states, whose thoughts occupied higher regions than those of men of more mundane interests:

He was a worshipper of INTELLECT — longing to grasp the power of mind that moves the stars — to bathe his soul in the dreams of seraphs. He was himself all ethereal, of a fine essence, that moved in an atmosphere of spirits — of spiritual beauty, overflowing and radiant — twin brother with the angels, feeling their flashing wings upon his heart, and almost clasping them in his embrace. Of them, and as an expectant archangel of that high order of intellect, stepping out of himself, as it were, and interpreting the time, he reveled in delicious luxury in a world beyond, with an audacity which we fear in madmen, but in genius worship as the inspiration of heaven.It should be observed that contemporary critics hold a view of Poe that is much closer to Graham’s estimation of the author than to Griswold’s caricature of him.

Note: Both Griswold’s obituary and Graham’s eulogy may be read in their entireties at “A Poe Bookshelf: Books, Articles and Lectures on Edgar Allan Poe,” courtesy of The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore.

Wednesday, February 17, 2010

Horror Masters

On this same site, you will also find, absolutely free, works by L. Frank Baum, Ambrose Bierce, Algernon Blackwood, Willa Cather, G. K. Chesterton, Sir Winston Churchill, Christabel Coleridge, Joseph Conrad, Stephen Crane, Lord Dunsany, Eugene Field, E. M. Forster, Elizabeth Gaskell, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Ellen Glasgow, Oliver Goldsmith, Maxim Gorky, H. Rider Haggard, Edward Everett Halle, Thomas Hardy, O. Henry, William Hope Hodgson, William Dean Howells, W. W. Jacobs, Henry James, M. R. James, Franz Kafka, Jerome K. Jerome, Rudyard Kipling, D. H. Lawrence, Sinclair Lewis, Jack London, Arthur Machen, Katherine Mansfield, Guy De Maupassant, Brander Matthews, A. Merritt, John Metcalf, Edith Nesbit, Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch, Damon Runyon, Saki, George Bernard Shaw, Robert Louis Stevenson, Frank R. Stockton, Leo Tolstoy, H. G. Wells, Edith Wharton, Walt Whitman, Virginia Woolf, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and W. B. Yeats.

There are non-fiction stories, novels, novellas, short stories, poems, early and late Gothics, and such categories from which to choose as “Classic Horror,” “Dark Stuff,” “Ghost Stories,” “Horror History,” “Monsters,” “Occult,” “Psychos,” and “The X-treme,” which includes “Decadent Traditions in Horror,” including works by the Marquis de Sade, Giovanni Boccaccio, and others.

Stories are listed both by writer and by title. You’ll find names as familiar as your own and altogether unknown, but the creator Horror Masters has compiled a huge list of winners, and they’re absolutely free!

Saturday, May 9, 2009

Summer Morning, Summer Night: A Review

Ray Bradbury has made quite a career out of nostalgia, and his affectionate respect for the past continues to serve him well in Summer Morning, Summer Night (2008), a collection of short stories unified by the common setting of Green Town, Illinois. Not altogether unlike Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, which Bradbury admits influenced the structure, if not the contents, of The Martian Chronicles, this anthology is gentler and more sensitive than Anderson’s gallery of the grotesque tended to be. The characters, however, are often eccentric in their own ways, and most are, like their author, sensitive and understated, even in their eccentricity.

The first story in the collection, “End of Summer,” concerns a sexually repressed schoolteacher, thirty-five-year-old Hattie, who lives with her grandmother, aunt, and cousin, who are equally straight-laced and no-nonsense. Although Hattie fears being found out by one of them, she also defies their narrow, emotionless, sexless lives. She has repressed her own sexuality, but, in this story, she throws caution to the winds. In fact, she has apparently taken some risks even before the story proper commences. She is a voyeur; in this tale, she becomes, also, a seductress. She seems to delight in outraging her family’s stern sense of propriety, even if she does so in secret. It is enough for her, it appears, that she knows that she has violated their taboos.

As the story opens, she lies awake in her room, counting “the long, slow strokes of the high town clock” (9). Judging by her count, it is two o’clock in the morning, and the streets are deserted. She rises from her bed, applies makeup, polishes her fingernails, dabs perfume behind her ears, casts off her “cotton nightgown” in favor of a negligee, and lets down her hair (9). Gazing into her mirror, she is satisfied with the image of herself that meets her gaze:

She saw the long, dark rush of her hair in the mirror as she unknotted the tight schoolteacher’s bun and let it fall loose to her shoulders. Wouldn’t her pupils be surprised. She thought; so long, so black, so glossy. Not bad for a woman of thirty-five (9).Having donned the uniform of a literal lady of the evening, Hattie sneaks past the closed doors of her grandmother, aunt, and cousin, anxious that one or more of them might choose this moment to exit their bedroom, but, despite her nervousness, nevertheless pauses to stick “her tongue out at one door, then at the other two” (10).

Outside, she pauses to enjoy the sensations of the “wet grass,” which is “cool and prickly,” and, after dodging the “patrolman, Mr. Waltzer,” surveys the town from the vantage point of the courthouse rooftop before sneaking from house to house to eavesdrop and spy upon their residents (10).

One of the men upon whom she spies follows her, and she seduces him--or perhaps it is he who seduces her. In the night, when darkness and shadows rule, passions are abroad in the darkness, and it is difficult to say, sometimes, who is the predator and who the prey. It may be that both are seducers, just as both are seduced.

After the assignation, Hattie returns to the house she shares with Grandma, Aunt Maude, and Cousin Jacob, no longer wearing cosmetics, dressed primly, and behaving properly, except for the smile she seems unable to shed, even in the austere presence of her repressive kinsmen, who chastise her for being late to rise and tardy to work. She leaves their company, still smiling as she runs out of the house, the door slamming behind her.

In this story, the monster is not the typical bogeyman, but the strict propriety of the prim and proper family of which Hattie both is and is not a member. A synecdoche of society itself, the rigid demand for conformity and the repression of personal passion of which has a debilitating effect upon the individual human spirit because it represses the fleshly aspects of human existence, Hattie’s family and its unyielding demands for steadfast respectability, at the very cost of one’s soul, suggests that it is inhuman to deny one’s physical appetites.

In demanding that these vital elements of their personalities be repressed, her relatives become more like machines that saintly souls, whereas, because of her covert rebelliousness, which allows her to remain true to herself, including the passions and appetites of her fleshly existence, Hattie shows the monstrosity that hides behind the familial and social demands for sexual repression and emotional rigidity. Ironically, her behavior, which would, no doubt, scandalize her family, as it would her community, is the salvation, rather than the ruination, of her soul. Her actions stand as a silent, even secret, rebuke to the harshness of an overly restrictive and conventional lifestyle. Hattie dares not disturb the universe--or even her own household--but, in private, she finds the sexual release that is denied to her in the public arena of her life, and these nocturnal assignations, brief as they may be, are enough to bring a smile to her lips that does not fade. The private life is all we have, Bradbury suggests, but it is enough when one finds another with a similar attitude and similar needs with whom to share it. Sometimes, heroism is as quiet and as passive-aggressive as the rebellious, but discreet, protagonist of this gentle tale of gallantry and pluck.

This story is itself a synecdoche, as it were, for the entire anthology of which it is the first flower. The other stories are just as delicate, just as beautiful, just as perfumed with the scents of joy and sorrow, reminiscence and lament, magic and wisdom. Most of all, they are instances of poetry, prose poems which assert, each one, in its own way, the enchantments and mysteries of life, as they manifest themselves in things both small enough to go unnoticed by all but the most sensitive and discerning and large enough to shake children and adult alike with laughter or with tears. A slender volume, Summer Morning, Summer Night is as deep and broad as the gray-haired man who, in writing it, packed every page and paragraph with as much Green Haven, Illinois, as would fit. The book shows why Ray Bradbury remains a treasure as much today as he was when he first broached the enchanted wonderland of modern middle America, well over half a century ago.

Wednesday, December 17, 2008

"Christabel": The Prototypical Lesbian Vampire

She’s sweet and chaste and pure and innocent and sexy and girl-next-door and religious and probably blonde, and she’s named Christabel. She’s the victim.

Her dark half and lover is mysterious and sexually experienced and seductive and exotic and blasphemous and probably brunette, and she’s named Geraldine. She’s the prototypical lesbian vampire.

Reveler upon opium when he was not writing poetry or literary criticism (or dodging bill collectors), poor, but brilliant, Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote, among other eerie poems, such as The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and “Kubla Khan,” a narrative ditty about a lesbian vampire named Christabel. It has gotten relatively short shrift among publishers and is not as well known among the general public as other of the poet’s works. If one has encountered the poem at all, it was most likely during a class concerning poetry or English literature. It is a disturbing poem, and, since it involves a good deal of horror, terror, revulsion, and abnormality, it is a good subject for study by horror writers, professional and aspiring.

While praying beside an oak tree in the wee hours of the morning, Christabel encounters a strange stranger named Geraldine, who says men have abducted her from her home. Enchanted by Geraldine’s seductive beauty, Christabel, perhaps knowing a good thing when she sees it (she may even regard Geraldine as a response to her prayer), takes the stranger home with her, whereupon Christabel’s father, Sir Leoline, a baron, becoming infatuated with Geraldine, orders a celebratory parade to declare her rescue. Here, the poem (another of Cole ridge’s “fragments”) ends, although the poet is alleged to have intended to finish it according to this storyline, identified by Coleridge’s biographer, James Gilman:

The verse is almost adolescent, or, as critics prefer to say, when addressing the work of a member of the literary canon, childlike:Over the mountains, the Bard, as directed by Sir Leoline, hastes with his disciple; but in consequence of one of those inundations supposed to be common to this country, the spot only where the castle once stood is discovered--the edifice itself being washed away. He determines to return. Geraldine, being acquainted with all that is passing, like the weird sisters in Macbeth, vanishes. Reappearing, however, she awaits the return of the Bard, exciting in the meantime, by her wily arts, all the anger she could rouse in the Baron's breast, as well as that jealousy of which he is described to have been susceptible. The old Bard and the youth at length arrive, and therefore she can no longer personate the character of Geraldine, the daughter of Lord Roland de Vaux, but changes her appearance to that of the accepted, though absent, lover of Christabel. Now ensues a courtship most distressing to Christabel, who feels--she knows not why--great disgust for her once favored knight.

This coldness is very painful to the Baron, who has no more conception than herself of the supernatural transformation. She at last yields to her father's entreaties, and consents to approach the altar with the hated suitor. The real lover, returning, enters at this moment, and produces the ring which she had once given him in sign of her. . . [betrothal]. Thus defeated, the supernatural being Geraldine disappears. As predicted, the castle bell tolls, the mother's voice is heard, and, to the exceeding great joy of the parties, the rightful marriage takes place, after which follows a reconciliation and explanation between father and daughter.

Coleridge not-so-subtly plants some clues that Geraldine may be as monstrous as she is beautiful, for she refuses to thank the Virgin Mary for her rescue:‘Tis the middle of night by the castle clock,

And the owls have awakened the crowing cock;

Tu--whit!-- Tu--whoo!

And hark, again! the crowing cock,

How drowsily it crew.Sir Leoline, the Baron rich,

Hath a toothless mastiff bitch;

From her kennel beneath the rock

She maketh answer to the clock,

Four for the quarters, and twelve for the hour;

Ever and aye, by shine and shower,

Sixteen short howls, not over loud;

Some say, she sees my lady's shroud.

Is the night chilly and dark?

The night is chilly, but not dark.

The thin gray cloud is spread on high,

It covers but not hides the sky.

Uh oh!So free from danger, free from fear,

They crossed the court : right glad they were.

And Christabel devoutly cried

To the Lady by her side,

Praise we the Virgin all divine

Who hath rescued thee from thy distress!

Alas, alas! said Geraldine, I cannot speak for weariness.

The fire likes her, too; it leaps in her presence, to show the reader, again, that there’s something odd about Geraldine:

Smitten by her seductress, mesmerizing houseguest, Christabel assures Geraldine that Christabel’s father sleeps: “O softly tread, said Christabel,/ My father seldom sleepeth well.” Is Christabel’s caution a concern for her father’s rest or an invitation of sexual dalliance with Geraldine? Their destination, and they stealthy way in which they approach it, suggests that Christabel may not be as innocent and virtuous as she appears to be, for she leads her houseguest, with the utmost caution, to her bedroom, where she offers her a glass of wine that Christabel’s now-deceased mother (and, presently, her “guardian spirit”) made from wildflowers:They passed the hall, that echoes still,

Pass as lightly as you will!

The brands were flat, the brands were dying,

Amid their own white ashes lying;

But when the lady passed, there came

A tongue of light, a fit of flame;

And Christabel saw the lady's eye,

And nothing else saw she thereby. . . .

The next moment, her name having been mentioned, the spirit of Christabel’s mother appears, but only Geraldine can see the phantom, and she orders the ghost to leave.Sweet Christabel her feet doth bare,

And jealous of the listening air

They steal their way from stair to stair,

Now in glimmer, and now in gloom,

And now they pass the Baron's room,

As still as death, with stifled breath!

And now have reached her chamber door;

And now doth Geraldine press down

The rushes of the chamber floor. . . .. . . O weary lady, Geraldine,

I pray you, drink this cordial wine!

It is a wine of virtuous powers;

My mother made it of wildflowers.

Invoking her authority to be alone with Christabel, Geraldine enforces her right, not wanting to be bothered by her enchanted hostess’ mother’s spirit hanging about like a spectral chaperone. Once the ghost has departed, Geraldine wastes no time in further seducing Christabel. She instructs Christabel to “unrobe” herself and to get into bed. Christabel does as she’s directed, obviously still under Geraldine’s spell. Unable to sleep, she studies Geraldine’s beautiful face and form, and the young hostess’ voyeurism is rewarded by a glimpse of Geraldine’s breast, which elicits a cry from the poem’s narrator for divine protection for Christabel:O mother dear! that thou wert here!

I would, said Geraldine, she were!But soon with altered voice, said she--

`Off, wandering mother! Peak and pine!

I have power to bid thee flee.'

Alas! what ails poor Geraldine?

Why stares she with unsettled eye?

Can she the bodiless dead espy?

And why with hollow voice cries she,

`Off, woman, off! this hour is mine--

Though thou her guardian spirit be,

Off, woman. off! 'tis given to me.'

Her charms having worked their magic, Geraldine, after a moment’s confused hesitation (probably included to make the meter work), gets into bed with Christabel, wherein they stretch out alongside one another, lay in one another’s arms, and, presumably, experience greater intimacies than those that a mere embrace may provide:But now unrobe yourself; for I

Must pray, ere yet in bed I lie.'Quoth Christabel, So let it be!

And as the lady bade, did she.

Her gentle limbs did she undress

And lay down in her loveliness.But through her brain of weal and woe

So many thoughts moved to and fro,

That vain it were her lids to close;

So half-way from the bed she rose,

And on her elbow did recline

To look at the lady Geraldine.Beneath the lamp the lady bowed,

And slowly rolled her eyes around;

Then drawing in her breath aloud,

Like one that shuddered, she unbound

The cincture from beneath her breast:

Her silken robe, and inner vest,

Dropt to her feet, and full in view,

Behold! her bosom, and half her side--

A sight to dream of, not to tell!

O shield her! shield sweet Christabel!

Yet Geraldine nor speaks nor stirs;At last, the mesmerizing Geraldine explains the magic of her enchanted “bosom” to her victim:

Ah! what a stricken look was hers!

Deep from within she seems half-way

To lift some weight with sick assay,

And eyes the maid and seeks delay;

Then suddenly as one defied

Collects herself in scorn and pride,

And lay down by the Maiden's side!--

And in her arms the maid she took. . . .!

And with low voice and doleful look

These words did say :

`In the touch of this bosom there worketh a spell,

Which is lord of thy utterance, Christabel!

So ends the first part of the poem, in which the princess Christabel, having befriended a strange, abducted woman, Geraldine, whom she’d met while she’d been praying in the woods near her father’s castle, shelters her for the night, only to be seduced by her houseguest’s beauty and to be spellbound by her magic breasts.

Despite the adolescent versification and the clumsy plot, the poem does have a certain seductive and mesmerizing effect upon the reader, drawing him or her into the magic of Geraldine’s enchanted “bosom” and suggesting that the poor, chaste Christabel, despite the narrator’s continued pleas for her protection, is, both sexually and otherwise, her houseguest’s victim:

Her slender palms together prest,It was a lovely sight to see

The lady Christabel, when she

Was praying at the old oak tree.

Amid the jaggéd shadows

Of mossy leafless boughs,

Kneeling in the moonlight,

To make her gentle vows.

Heaving sometimes on her breast;

Her face resigned to bliss or bale--

Her face, oh call it fair not pale,

And both blue eyes more bright than clear.

Each about to have a tear.:With open eyes (ah, woe is me!)

Asleep, and dreaming fearfully,

Fearfully dreaming, yet, I wis,

Dreaming that alone, which is--

O sorrow and shame! Can this be she,

The lady, who knelt at the old oak tree?

And lo! the worker of these harms,

That holds the maiden in her arms,

Seems to slumber still and mild,

As a mother with her child.

A star hath set, a star hath risen,

O Geraldine! since arms of thine

Have been the lovely lady's prison.

O Geraldine! one hour was thine--

Thou'st had thy will! By tairn and rill,

The night-birds all that hour were still.

But now they are jubilant anew,

From cliff and tower, tu--whoo! tu--whoo!

Tu--whoo! tu--whoo! from wood and fell!

And see! the lady Christabel

Gathers herself from out her trance;

Her limbs relax, her countenance

Grows sad and soft; the smooth thin lids

Close o'er her eyes; and tears she sheds--

Large tears that leave the lashes bright!

And oft the while she seems to smile

As infants at a sudden light!

Yea, she doth smile, and she doth weep,

Like a youthful hermitess,

Beauteous in a wilderness,

Who, praying always, prays in sleep.

And, if she move unquietly,

Perchance, 'tis but the blood so free

Comes back and tingles in her feet.

No doubt, she hath a vision sweet.

What if her guardian spirit 'twere,

What if she knew her mother near?

But this she knows, in joys and woes,

That saints will aid if men will call :

For the blue sky bends over all!.

No wonder lesbian and feminist critics regard this fragmented poem as one of the great ones of world lit.

The lesbian vampire has since become a staple of erotic horror, appearing in many legitimate, if “R”-rated, films, including:

Eternal (2004): Detective Raymond Pope’s search for his missing wife leads him to the estate of a wealthy woman, Elizabeth Kane, who may be the latest incarnation of Countess Elizabeth Bathory, the vampire who bathed in virgins’ blood.

Lost for a Vampire (1971): A writer researching a book visits an all-girls’ boarding school inhabited by lesbian vampire students.

Vampyros Lesbos (1971): In Turkey, American lawyer Linda Westinghouse’s dreams about being harassed and seduced by a dark-haired lesbian vampire beauty come true.

Les Frissons des Vampires (1970): Honeymooning couples are victimized by a castle of lesbian vampires.

Vampyres (1974): A lesbian couple lures innocent passersby to their deaths, one of the seductresses finally falling prey to a woman she seduces.

The Velvet Vampire (1971): A vampire woman comes out of the desert to seduce a hippie couple.

The Vampire Lovers (1970): The first of a trilogy of films about lesbian vampires, this one recreates, more or less faithfully, Sheridan LeFanu’s novel, Camilla. The lesbian is rival against a man for the affections of a woman whom both desire. He wins.

Blood and Roses (1960): A dead vampire’s spirit lives again by possessing Camilla, who narrates the tale.

Daughters of Darkness (1971): A honeymooning couple encounters Countess Elizabeth Bathory, who seduces the bride.

The Hunger (1983): Miriam Blaylock seduces scientist Sarah Roberts.

One into which it was harder for some critics to sink their teeth into is Lesbian Vampire Killers (to be released in 2009), a comedy in which men seek to rescue their women from a gang of lesbian vampires who have victimized a small Welsh town.

Monday, August 11, 2008

The Birth of Monsters and Other Poems

In previous posts ("Horrific Poems: A Sampler" and "Charles Baudelaire's 'Carrion'"), I shared a few poems in the horror genre. In this post, I'm sharing a few of my own verses, which, hopefully, will be found diabolical enough to thrill, if not to chill.

I chose the sonnet because of its rhyme scheme. The sonnet form I've selected requires that, in the first twelve lines, the last word of each alternate line must rhyme. It also requires that the last two lines constitute a rhyming couplet. The overall rhyme scheme often forces an image, a trope, a thought, or a sentiment, thereby, helping, as it were, to write the poem itself, as if the rhyme scheme were something of a muse.

To The Wind

The wind blows free, but you and me,

We are captives, bound by a force

Mightier than stone, field, or tree:

Gravity determines our course.

Within the confines of the earth,

We may go wand'ring as we please;

Our minds may conceive and bring forth

Flights of fancy, winged fantasies,

Divorced of flesh and wed to naught,

With no authority to say

Nay, ye have transcended what ought

Be thought or tried by mortal clay.

Fettered by our humanity,

A faint breeze is cause for envy.

The Birth of Monsters

Beneath the canopies of trees, shadows,

Thick and dark, fall across stained, moss-covered

Headstones, and the rising winter’s wind blows;

Leafless branches, like clawed fingers, scratch; stirred,

By a sudden gust, wreaths and flowers leap

From vases overturned, blow and scatter,

And, were the cadavers not buried deep,

They might, clotted with gore and blood-splattered,

Rise from their coffins and their graves, to reel

And stagger across the dark churchyard’s grounds,

Insensible and unable to feel,

Among the tombs and the burial mounds.

Look! Listen! The imagination warns;

Of such wild nights are ghastly monsters born!

The Great Debate

In life, the skeptic and the man of faith

Each sought to refute the other one’s view,

The former claiming that to see a wraith

Meant one had lost his reason, for, ‘tis true,

That quick is quick and dead is dead; buried,

Bodies are removed from society,

Fit for naught but food on which worms may feed.

The latter argued that the soul, set free

By the body’s death, ascends unto God,

In whose image and likeness it was made,

Leaving but mortal flesh beneath the sod,

The transcendent spirit beyond decay.

Their passionate arguments have long since

Ended, unsure--by their own deaths silenced.

Fiendish Kinsmen

Winged, fanged things with claws, vague and indistinct,

Haunt the dark; furtive and stealthy, seldom

Are they seen, for which reason they are linked,

More often than not, with nightmare or some

Horrid fantasy, reason’s predators,

Slimed in mucus and enveloped in blood,

Stalking, or creeping, or slinking through gore,

Vile, evil things unseen since Noah’s flood,

The very spawn, perhaps, of murd’rous Cain,

Living embodiments of sin, exiled

From Eden, homeless, now, but for the brain

Of man, whose thoughts are both wicked and wild.

Not once were these mad fiends clearly described,

Yet we know them well, for we’re of their tribe.

The Book of Art, the Book of Life

The image, metaphor, and symbol each

Is plucked, as a leaf, from the tree of life

That it, pressed within an art book, may teach

The lesson of sorrow, anguish, or strife.

Authors may select a flower, a dove,

An ocean liner cruising the vast deep,

A rainbow shining in the sky above,

Or a road winding up a mountain steep;

Wordsworth wrote of a cloud of daffodils

Beneath a clear sky, both bright and azure,

Keats of a granary at autumn filled,

And Blake of a lamb, wooly-bright and pure;

Only in poems by Baudelaire and Poe

Does art blush to see blood and guts on show.

The Roulette Wheel

The roulette wheel, having been twirled, must whirl,

Its silver ball leaping from red to black,

Having, from the Croupier’s hand been hurled,

A fortune risked upon its fateful track.

Past the even and the odd, the small ball

Runs round the tilted track within the wheel;

Where it shall stop, no one yet knows, but all

Watch, transfixed, to see which fate it shall seal--

In Europe, thirty seven chances be,

One more in American destinies:

In the modern world, our technology

Has replaced the Norns, Moirae, and Parcae:

The wheel spins with pain, grief, and misery,

Red blood, black death, and silvery decay.

Friday, August 8, 2008

Charles Baudelaire’s “Carrion”

In a previous post, we shared several relatively short poems that express horrific themes. In this post, we share Charles Baudelier’s “Carrion,” a strange rhyme, indeed, and appalling.

First, the poem; then, the commentary:

Remember, my soul, the thing we saw

that lovely summer day?

On a pile of stones where the path turned off

the hideous carrion--

legs in the air, like a whore--displayed

indifferent to the last,

a belly slick with lethal sweat

and swollen with foul gas.

the sun lit up that rottenness

as though to roast it through,

restoring to Nature a hundredfold

what she had here made one.

And heaven watched the splendid corpse

like a flower open wide--

you nearly fainted dead away

at the perfume it gave off.

Flies kept humming over the guts

from which a gleaming clot

of maggots poured to finish off

what scraps of flesh remained.

The tide of trembling vermin sank,

then bubbled up afresh

as if the carcass, drawing breath,

by their lives lived again

and made a curious music there--

like running water, or wind,

or the rattle of chaff the winnower

loosens in his fan.

Shapeless--nothing was left but a dream

the artist had sketched in,

forgotten, and only later on

finished from memory.

Behind the rocks an anxious bitch

eyed us reproachfully, waiting for

the chance to resume

her interrupted feast.

--Yet you will come to this offence,

this horrible decay, you, the

light of my life, the sun

and moon and stars of my love!

Yes, you will come to this, my queen,

after the sacraments,

when you rot underground among

the bones already there.

But as their kisses eat you up,

my Beauty, tell the worms

I've kept the sacred essence, saved

the form of my rotted loves!

Some time after the incident (“the thing we saw/ that lovely summer day”), still haunted, it appears, by the sight, the speaker of the poem recalls having seen, while walking with his lover, the dead and bloated carcass of a maggot-infested beast. In describing the animal’s “corpse” as he reminisces about the sight to his girlfriend, thus keeping alive in his memory the appalling sight, he mixes distasteful images and adjectives that bespeak unpleasant qualities and states with images and adjectives that express agreeable and pleasant characteristics and conditions:

“thing,” “carrion,” “whore,” “sweat,” “gas,” “rottenness,” “corpse,” “flower,” “perfume,” “flies,” “guts,” “maggots,” “scraps of flesh,” “vermin,” “carcass,” “music,” “water,” “wind,” “fan,” “bitch,” “feast,” “offence,” “decay,” “queen,” “sacraments,” “kisses,” “Beauty,” “worms.”

The negative images and descriptive words and phrases suggest his disgust, but, strangely, it is a disgust that merges with attraction. He is fascinated, it seems, with what he considers the beauty of death as it is represented in the concrete and vivid spectacle of an animal’s decomposing carcass. The rotting nature of the body seems to show life’s dirty little secret, as it were: the reality (death, or nothingness) that is hidden at the center of existence.

Nature does not discriminate in its destructiveness to accord with human perceptions and prejudices of good and evil, beauty and ugliness, and value and insignificance, but kills and dismantles all. In doing so, it feeds upon itself, life deriving sustenance from the effects of death, as the flies feed upon the carcass and lay eggs that, as “maggots,” can later “finish off/ what scraps of flesh” remain, the crumbs, as it were, of the flies and dogs’ “feast.”

The speaker next personalizes death by applying the lesson he has learned from having seen the dead animal to the eventual fate of his girlfriend, observing that she, too, “will come to this offence,/ this horrible decay,” despite her religious faith, as indicated by the “sacraments,” and “rot underground among/ the bodies already there.” Death will not spare her, any more than it has spared others of her faith or, for that matter, those of no faith. Again, death is indiscriminate in its destructiveness, and neither faith nor disbelief avails against one's demise.

He ends his reminiscence and commentary upon the experience of having come across the dead animal’s rotten and bloated body by foreseeing, as it were, an ironic future situation, asking his lover to imagine herself, conscious despite her death and being devoured by “worms” whose “kisses eat” her, that he, in having survived her (for a time, at least), has “kept the sacred essence” and “saved/ the form of” his “rotted loves.” Moreover, he makes her, his “queen,” an embodiment of “Beauty,” addressing her as such.

This appellation may refer to the last lines of John Keats' “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,--that is all/ Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know,” Keats wrote. Regardless of what these closing lines of Keats’ poem may mean (critics continue to debate the issue), it is truly chilling to suppose, as Baudelaire’s speaker seems to imagine, that the truth, concerning “Beauty,” is that it must, like a lovely woman, end in death, in nothingness, and in absurdity, just as love itself must end.

In such a poem, there is no hope, nor is there any reason to suggest that the repulsive and the beautiful, in the final analysis, signify any difference. If death and destruction are the end of life, of beauty, and of love, death, ugliness, and apathy are no better or worse than one another, and good and evil themselves become but moot and meaningless points.

Paranormal vs. Supernatural: What’s the Diff?

Sometimes, in demonstrating how to brainstorm about an essay topic, selecting horror movies, I ask students to name the titles of as many such movies as spring to mind (seldom a difficult feat for them, as the genre remains quite popular among young adults). Then, I ask them to identify the monster, or threat--the antagonist, to use the proper terminology--that appears in each of the films they have named. Again, this is usually a quick and easy task. Finally, I ask them to group the films’ adversaries into one of three possible categories: natural, paranormal, or supernatural. This is where the fun begins.

It’s a simple enough matter, usually, to identify the threats which fall under the “natural” label, especially after I supply my students with the scientific definition of “nature”: everything that exists as either matter or energy (which are, of course, the same thing, in different forms--in other words, the universe itself. The supernatural is anything which falls outside, or is beyond, the universe: God, angels, demons, and the like, if they exist. Mad scientists, mutant cannibals (and just plain cannibals), serial killers, and such are examples of natural threats. So far, so simple.

What about borderline creatures, though? Are vampires, werewolves, and zombies, for example, natural or supernatural? And what about Freddy Krueger? In fact, what does the word “paranormal” mean, anyway? If the universe is nature and anything outside or beyond the universe is supernatural, where does the paranormal fit into the scheme of things?

According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word “paranormal,” formed of the prefix “para,” meaning alongside, and “normal,” meaning “conforming to common standards, usual,” was coined in 1920. The American Heritage Dictionary defines “paranormal” to mean “beyond the range of normal experience or scientific explanation.” In other words, the paranormal is not supernatural--it is not outside or beyond the universe; it is natural, but, at the present, at least, inexplicable, which is to say that science cannot yet explain its nature. The same dictionary offers, as examples of paranormal phenomena, telepathy and “a medium’s paranormal powers.”

Wikipedia offers a few other examples of such phenomena or of paranormal sciences, including the percentages of the American population which, according to a Gallup poll, believes in each phenomenon, shown here in parentheses: psychic or spiritual healing (54), extrasensory perception (ESP) (50), ghosts (42), demons (41), extraterrestrials (33), clairvoyance and prophecy (32), communication with the dead (28), astrology (28), witchcraft (26), reincarnation (25), and channeling (15); 36 percent believe in telepathy.

As can be seen from this list, which includes demons, ghosts, and witches along with psychics and extraterrestrials, there is a confusion as to which phenomena and which individuals belong to the paranormal and which belong to the supernatural categories. This confusion, I believe, results from the scientism of our age, which makes it fashionable for people who fancy themselves intelligent and educated to dismiss whatever cannot be explained scientifically or, if such phenomena cannot be entirely rejected, to classify them as as-yet inexplicable natural phenomena. That way, the existence of a supernatural realm need not be admitted or even entertained. Scientists tend to be materialists, believing that the real consists only of the twofold unity of matter and energy, not dualists who believe that there is both the material (matter and energy) and the spiritual, or supernatural. If so, everything that was once regarded as having been supernatural will be regarded (if it cannot be dismissed) as paranormal and, maybe, if and when it is explained by science, as natural. Indeed, Sigmund Freud sought to explain even God as but a natural--and in Freud’s opinion, an obsolete--phenomenon.

Meanwhile, among skeptics, there is an ongoing campaign to eliminate the paranormal by explaining them as products of ignorance, misunderstanding, or deceit. Ridicule is also a tactic that skeptics sometimes employ in this campaign. For example, The Skeptics’ Dictionary contends that the perception of some “events” as being of a paranormal nature may be attributed to “ignorance or magical thinking.” The dictionary is equally suspicious of each individual phenomenon or “paranormal science” as well. Concerning psychics’ alleged ability to discern future events, for example, The Skeptic’s Dictionary quotes Jay Leno (“How come you never see a headline like 'Psychic Wins Lottery'?”), following with a number of similar observations:

Psychics don't rely on psychics to warn them of impending disasters. Psychics don't predict their own deaths or diseases. They go to the dentist like the rest of us. They're as surprised and disturbed as the rest of us when they have to call a plumber or an electrician to fix some defect at home. Their planes are delayed without their being able to anticipate the delays. If they want to know something about Abraham Lincoln, they go to the library; they don't try to talk to Abe's spirit. In short, psychics live by the known laws of nature except when they are playing the psychic game with people.In An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural, James Randi, a magician who exercises a skeptical attitude toward all things alleged to be paranormal or supernatural, takes issue with the notion of such phenomena as well, often employing the same arguments and rhetorical strategies as The Skeptic’s Dictionary.

In short, the difference between the paranormal and the supernatural lies in whether one is a materialist, believing in only the existence of matter and energy, or a dualist, believing in the existence of both matter and energy and spirit. If one maintains a belief in the reality of the spiritual, he or she will classify such entities as angels, demons, ghosts, gods, vampires, and other threats of a spiritual nature as supernatural, rather than paranormal, phenomena. He or she may also include witches (because, although they are human, they are empowered by the devil, who is himself a supernatural entity) and other natural threats that are energized, so to speak, by a power that transcends nature and is, as such, outside or beyond the universe. Otherwise, one is likely to reject the supernatural as a category altogether, identifying every inexplicable phenomenon as paranormal, whether it is dark matter or a teenage werewolf. Indeed, some scientists dedicate at least part of their time to debunking allegedly paranormal phenomena, explaining what natural conditions or processes may explain them, as the author of The Serpent and the Rainbow explains the creation of zombies by voodoo priests.

Based upon my recent reading of Tzvetan Todorov's The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to the Fantastic, I add the following addendum to this essay.

According to Todorov:

The fantastic. . . lasts only as long as a certain hesitation [in deciding] whether or not what they [the reader and the protagonist] perceive derives from "reality" as it exists in the common opinion. . . . If he [the reader] decides that the laws of reality remain intact and permit an explanation of the phenomena described, we can say that the work belongs to the another genre [than the fantastic]: the uncanny. If, on the contrary, he decides that new laws of nature must be entertained to account for the phenomena, we enter the genre of the marvelous (The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre, 41).Todorov further differentiates these two categories by characterizing the uncanny as “the supernatural explained” and the marvelous as “the supernatural accepted” (41-42).

Interestingly, the prejudice against even the possibility of the supernatural’s existence which is implicit in the designation of natural versus paranormal phenomena, which excludes any consideration of the supernatural, suggests that there are no marvelous phenomena; instead, there can be only the uncanny. Consequently, for those who subscribe to this view, the fantastic itself no longer exists in this scheme, for the fantastic depends, as Todorov points out, upon the tension of indecision concerning to which category an incident belongs, the natural or the supernatural. The paranormal is understood, by those who posit it, in lieu of the supernatural, as the natural as yet unexplained.

And now, back to a fate worse than death: grading students’ papers.

My Cup of Blood

Anyway, this is what I happen to like in horror fiction:

Small-town settings in which I get to know the townspeople, both the good, the bad, and the ugly. For this reason alone, I’m a sucker for most of Stephen King’s novels. Most of them, from 'Salem's Lot to Under the Dome, are set in small towns that are peopled by the good, the bad, and the ugly. Part of the appeal here, granted, is the sense of community that such settings entail.

Isolated settings, such as caves, desert wastelands, islands, mountaintops, space, swamps, where characters are cut off from civilization and culture and must survive and thrive or die on their own, without assistance, by their wits and other personal resources. Many are the examples of such novels and screenplays, but Alien, The Shining, The Descent, Desperation, and The Island of Dr. Moreau, are some of the ones that come readily to mind.

Total institutions as settings. Camps, hospitals, military installations, nursing homes, prisons, resorts, spaceships, and other worlds unto themselves are examples of such settings, and Sleepaway Camp, Coma, The Green Mile, and Aliens are some of the novels or films that take place in such settings.

Anecdotal scenes--in other words, short scenes that showcase a character--usually, an unusual, even eccentric, character. Both Dean Koontz and the dynamic duo, Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, excel at this, so I keep reading their series (although Koontz’s canine companions frequently--indeed, almost always--annoy, as does his relentless optimism).

Atmosphere, mood, and tone. Here, King is king, but so is Bentley Little. In the use of description to terrorize and horrify, both are masters of the craft.

Believable characters. Stephen King, Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, and Dan Simmons are great at creating characters that stick to readers’ ribs.

Innovation. Bram Stoker demonstrates it, especially in his short story “Dracula’s Guest,” as does H. P. Lovecraft, Edgar Allan Poe, Shirley Jackson, and a host of other, mostly classical, horror novelists and short story writers. For an example, check out my post on Stoker’s story, which is a real stoker, to be sure. Stephen King shows innovation, too, in ‘Salem’s Lot, The Shining, It, and other novels. One might even argue that Dean Koontz’s something-for-everyone, cross-genre writing is innovative; he seems to have been one of the first, if not the first, to pen such tales.

Technique. Check out Frank Peretti’s use of maps and his allusions to the senses in Monster; my post on this very topic is worth a look, if I do say so myself, which, of course, I do. Opening chapters that accomplish a multitude of narrative purposes (not usually all at once, but successively) are attractive, too, and Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child are as good as anyone, and better than many, at this art.

A connective universe--a mythos, if you will, such as both H. P. Lovecraft and Stephen King, and, to a lesser extent, Dean Koontz, Bentley Little, and even Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child have created through the use of recurring settings, characters, themes, and other elements of fiction.

A lack of pretentiousness. Dean Koontz has it, as do Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, Bentley Little, and (to some extent, although he has become condescending and self-indulgent of late, Stephen King); unfortunately, both Dan Simmons and Robert McCammon have become too self-important in their later works, Simmons almost to the point of becoming unreadable. Come on, people, you’re writing about monsters--you should be humble.

Longevity. Writers who have been around for a while usually get better, Stephen King, Dan Simmons, and Robert McCammon excepted.

Popular Posts

-

Copyright 2011 by Gary L. Pullman While it is not the intent of Chillers and Thrillers to titillate its readers, no series concerning s...

-

Copyright 2008 by Gary L. Pullman Let’s begin with descriptions, by yours truly, of three Internet images. But, first, a brief digress...

-

Copyright 2011 by Gary L. Pullman Gustav Freytag analyzed the structure of ancient Greek and Shakespearean plays, dividing them in...

-

Copyright 2019 by Gary L. Pullman After his father's death, Ed Gein (1906-1984) was reared by his mother, a religious fanati...

-

Copyright 2010 by Gary L. Pullman The military has a new approach to taking down the dome: “an experimental acid” that is powerful enough to...

-

Copyright 2011 by Gary L. Pullman One way to gain insight concerning horror writers’ fiction and the techniques that the writers of ...

-

Copyright 202 by Gary L. Pullman King Edward III The first sentence of the story establishes its setting: it is “about twelve o...

-

Copyright 2011 by Gary L. Pullman Okay, I admit it: I have never seen a demon. Not a real one, not a demon in the flesh, as it were....

-

Copyright 2011 by Gary L. Pullman Although he employs psychoanalysis himself on rare occasions in his analyses of and commentaries upon ...