Copyright 2018 by Gary L. Pullman

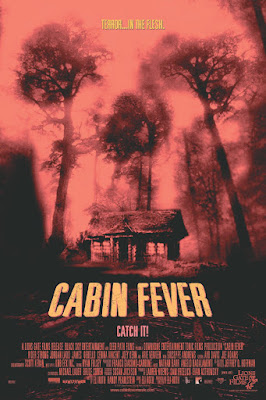

Horror posters are like

the covers of horror novels, except the former's production quality

is usually far superior to that of a paperback's cover art.

Extending the comparison, we could say that the movie's trailer is

cinematic equivalent of the blurb on the inside flap of the dust

cover or the back of a paperback. Both introduce the main character,

the villain, and the conflict, the trailer in dramatic, audio-visual

terms, the blurb in narrative, linguistic fashion. The former has

immediacy; the latter, not so much.

Today, both posters and book covers often have only a marginal relationship to the story's plot. (Those of yesteryear seem to have been more closely associated with the story.) In general, the trailers and blurbs are more trustworthy indicators of what happens in the movie or the novel.

Contemporary movie posters (more than present-day novels' cover art) seek to tap into their viewers' emotions. Whether the movie's an action-adventure film, a comedy, a detective movie, a fantasy, a horror film, a mystery, a romance, sci-fi, a western, or some other genre or a hybrid of some sort, its poster will tap into such feelings as awe, delight, wonder, fear, and bewilderment, suggesting that the film that the poster advertises will immerse viewers in such emotional experiences.

Today, both posters and book covers often have only a marginal relationship to the story's plot. (Those of yesteryear seem to have been more closely associated with the story.) In general, the trailers and blurbs are more trustworthy indicators of what happens in the movie or the novel.

Contemporary movie posters (more than present-day novels' cover art) seek to tap into their viewers' emotions. Whether the movie's an action-adventure film, a comedy, a detective movie, a fantasy, a horror film, a mystery, a romance, sci-fi, a western, or some other genre or a hybrid of some sort, its poster will tap into such feelings as awe, delight, wonder, fear, and bewilderment, suggesting that the film that the poster advertises will immerse viewers in such emotional experiences.

Huckleberry Finn, which is undoubtedly one of the great comedy masterpieces of American—or world—literature usually features an image of the adolescent hero rafting along the Mississippi River; Sherlock Holmes anthologies usually confront us with a close-up of the detective in his deerstalker cap, smoking his pipe; romance novels depict glamorous fashionistas being swept off their feet by bare-chested macho men; many a Western novel portrays a gunman of some sort or a solitary rider shown in silhouette against a dusky sky. In some cases, the cover art suggests emotion. Movie posters almost always do.

Find out how a movie poster suggests fear—and what type of fear it suggests—and you are well on the way to knowing how to convey such fears yourself in the stories you write.

Selecting a poster that implies a story is helpful, but, of course, the story it suggests has to be appropriate for the larger story you're telling, the larger narrative of which it, as a scene, would be a part.

Let's try a couple examples.

Here is a movie poster for The Conjuring (2013). What type of emotion does it convey? How does it convey this emotion? In other words, what artistic or rhetorical techniques are employed to convey this emotion? These are my responses to these questions. (Yours may differ.)

Emotion = fear of the unknown

Techniques:

symbolism, color, contrast

Using this analysis, write a descriptive paragraph, of 150 words or fewer, that accomplishes what the poster achieves. (In writing, description is the counterpart to the movie camera.) Then, you may want to break the paragraph into shorter ones. Here is one possibility:

Using this analysis, write a descriptive paragraph, of 150 words or fewer, that accomplishes what the poster achieves. (In writing, description is the counterpart to the movie camera.) Then, you may want to break the paragraph into shorter ones. Here is one possibility:

The

white flame burns brightly, lighting the darkness and the face of the

frightened woman holding the match. Framed by her blonde tresses, her

face is tense.

Her eyes are wide, her lips parted, as she stares into the darkness beyond the faint light, straining to see, as she strains to hear.

Between her forefinger and her thumb, the match quivers, its reduced flame flickering. Its faint light is all that stands between her and the unknown.

Soon, it will go out, and the darkness will swallow her again, and the thing for which she searches, lost in the gloom—will it lunge? Fall upon her? Rip, rend, and tear her?

Already, the flame is small and unsteady. Her hand shakes.

The darkness and the thing in the darkness wait. (131 words)

Her eyes are wide, her lips parted, as she stares into the darkness beyond the faint light, straining to see, as she strains to hear.

Between her forefinger and her thumb, the match quivers, its reduced flame flickering. Its faint light is all that stands between her and the unknown.

Soon, it will go out, and the darkness will swallow her again, and the thing for which she searches, lost in the gloom—will it lunge? Fall upon her? Rip, rend, and tear her?

Already, the flame is small and unsteady. Her hand shakes.

The darkness and the thing in the darkness wait. (131 words)

Here's a poster for the intended Halloween Returns film, which “was cancelled when Dimension Films lost the rights to the Halloween franchise.” Although the movie was never made, the poster suggests a scene that could fit into an original story. Since an original story couldn't use the characters from the Halloween series, the Laurie Strode character and the Michael Myers figure would have to be generic or fashioned after the characters of one's own story. This time, our description is a bit longer and more detailed.

Emotion =apprehension, anxiety

Techniques:

juxtaposition, colors (“lighting”), contrast

She

wore a blue sweater, not only because it was cool, but also, and more

importantly, because the color had a calming effect on her. Her

therapist, Ms. Phillips, had recommended pink, telling her that

prison walls had been painted this color because of its proven

soothing effect. But Jamie associated pink with femininity, and she

linked femininity to helplessness. After all, His victims had all

been women.

She slipped the point of the blade into the thick skin of the pumpkin. (If only her own shin were as thick!) She slid the blade deeper (just as He had done), and, with a twist of her wrist, cut across the surface of the orange orb. Pulp (like the deep tissues of her body) and juice (like the blood that had flowed from her that night) showed inside the squash.

Carving the pumpkins was supposed, like thepink

blue sweater, to calm her. “Using a knife,” she had challenged

her therapist, “to carve up pumpkins is supposed to have a calming

effect?” “Yes,” Ms. Phillips had reassured her. (Therapists,

Jamie had learned, were most reassuring.)

The top of the table at which she sat, carving pumpkins, was littered with seeds, with bits of pumpkin flesh, and with ornaments: ghosts and pumpkin heads (or headless pumpkins), and spiders' webs. “You have to get back into the holiday,” Ms. Phillips had suggested. “Make it yours again, instead of His.”

Spluttering candles were her only light. Behind and beside her, her house was dark. The light was enough to see by, enough to carve by. She Wasn't Afraid Of The Dark. That's what the candlelight proclaimed.

This was her third pumpkin. She'd carved traditional faces in them: big triangular eyes, a smaller upside-down triangle for a nose, and a grinning mouth missing all but two upper and a lower tooth. They were pumpkin-children old enough to lose their baby teeth in favor of the adult teeth to come. Innocent pumpkin faces, like her own was once, a long time ago, before He had returned home, not cured, no, but different. Worse. Much worse.

Behind her, in the gloom, a silent Figure moved as quietly as a black cat. Wearing a white mask that seemed to glow, even in the faint light of the candles, only His face—His mask—was visible. His dark clothing made Him part of the room's darkness. Only His mask, which hid His face, and the blade of the butcher's knife He held in His right fist, at His side, ready, were visible.

Halloween had come, and He'd come with it, to do a bit of carving of His own.

Amid the pain, He was going to make her smile; He was going to make her grin . . . again. (458 words)

She slipped the point of the blade into the thick skin of the pumpkin. (If only her own shin were as thick!) She slid the blade deeper (just as He had done), and, with a twist of her wrist, cut across the surface of the orange orb. Pulp (like the deep tissues of her body) and juice (like the blood that had flowed from her that night) showed inside the squash.

Carving the pumpkins was supposed, like the

The top of the table at which she sat, carving pumpkins, was littered with seeds, with bits of pumpkin flesh, and with ornaments: ghosts and pumpkin heads (or headless pumpkins), and spiders' webs. “You have to get back into the holiday,” Ms. Phillips had suggested. “Make it yours again, instead of His.”

Spluttering candles were her only light. Behind and beside her, her house was dark. The light was enough to see by, enough to carve by. She Wasn't Afraid Of The Dark. That's what the candlelight proclaimed.

This was her third pumpkin. She'd carved traditional faces in them: big triangular eyes, a smaller upside-down triangle for a nose, and a grinning mouth missing all but two upper and a lower tooth. They were pumpkin-children old enough to lose their baby teeth in favor of the adult teeth to come. Innocent pumpkin faces, like her own was once, a long time ago, before He had returned home, not cured, no, but different. Worse. Much worse.

Behind her, in the gloom, a silent Figure moved as quietly as a black cat. Wearing a white mask that seemed to glow, even in the faint light of the candles, only His face—His mask—was visible. His dark clothing made Him part of the room's darkness. Only His mask, which hid His face, and the blade of the butcher's knife He held in His right fist, at His side, ready, were visible.

Halloween had come, and He'd come with it, to do a bit of carving of His own.

Amid the pain, He was going to make her smile; He was going to make her grin . . . again. (458 words)

Such

exercises might raise the hair on the nape of your neck and your

arms; they might send chills along your spine; they might inspire a

story or enhance one you're already writing.